十九世纪美国诗歌

欧美近现代诗歌赏析一、19世纪浪漫主义文学1、华兹华斯(英):《丁登..

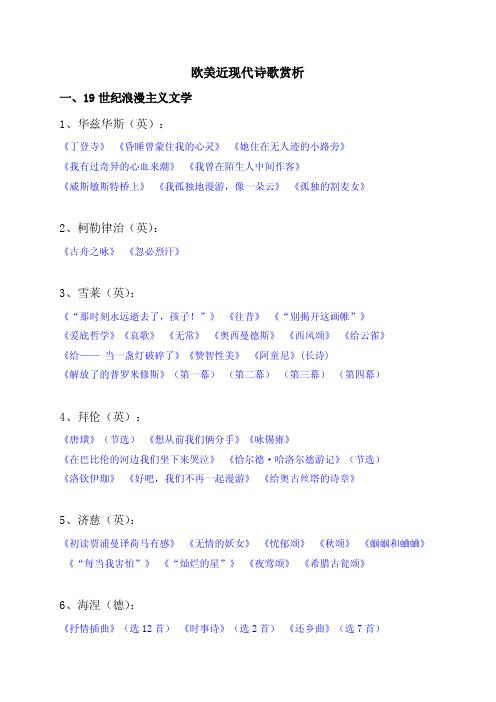

欧美近现代诗歌赏析一、19世纪浪漫主义文学1、华兹华斯(英):《丁登寺》《昏睡曾蒙住我的心灵》《她住在无人迹的小路旁》《我有过奇异的心血来潮》《我曾在陌生人中间作客》《威斯敏斯特桥上》《我孤独地漫游,像一朵云》《孤独的割麦女》2、柯勒律治(英):《古舟之咏》《忽必烈汗》3、雪莱(英):《“那时刻永远逝去了,孩子!”》《往昔》《“别揭开这画帷”》《爱底哲学》《哀歌》《无常》《奥西曼德斯》《西风颂》《给云雀》《给——当一盏灯破碎了》《赞智性美》《阿童尼》(长诗)《解放了的普罗米修斯》(第一幕)(第二幕)(第三幕)(第四幕)4、拜伦(英):《唐璜》(节选)《想从前我们俩分手》《咏锡雍》《在巴比伦的河边我们坐下来哭泣》《恰尔德·哈洛尔德游记》(节选)《洛钦伊珈》《好吧,我们不再一起漫游》《给奥古丝塔的诗章》5、济慈(英):《初读贾浦曼译荷马有感》《无情的妖女》《忧郁颂》《秋颂》《蝈蝈和蛐蛐》《“每当我害怕”》《“灿烂的星”》《夜莺颂》《希腊古瓮颂》6、海涅(德):《抒情插曲》(选12首)《时事诗》(选2首)《还乡曲》(选7首)7、普希金(俄):《致恰阿达耶夫》《致克恩》《纪念碑》《致大海》《欧根·奥涅金》节选、《巴奇萨拉的喷泉》8、惠特曼(美):《我听见美国在歌唱》《一只沉默而耐心的蜘蛛》《哦.船长,我的船长!》《我在路易斯安那看见一棵栎树在生长》《眼泪》《黑夜里在海滩上》《从滚滚的人海中一小时的狂热和喜悦》《我自己的歌》(节选)9、爱伦·坡(美):《致海伦》《安娜蓓尔·李》《最快乐的日子》《乌鸦》《梦》《模仿》《湖——致——》二、19世纪象征主义文学1、魏尔伦(法):《感伤的对话》《月光曲》《白色的月》《泪流在我心里》《狱中》《小夜曲》《秋歌》《多情的散步》《神秘之夜的黄昏》《夕阳》《苦恼》《我不知道为什么》《在你还没有消失……》2、波德莱尔(法):《应和》《从前的生活》《异域的芳香》《头发》《阳台》《黄昏的和谐》《秋歌》《猫》《风景》《赌博》《高翔远举》《人与海》《月亮的哀愁》《忧伤与漂泊》《秋之十四行诗》《毁灭》《祝福》3、马拉美(法):《太空》《夏愁》《天鹅》《叹息》《回春》《撞钟人》《牧神的午后》《海风》4、韩波(法):《醉舟》《黄昏》《元音》《奥菲利娅》《牧神的头》《乌鸦》《童年》三、19世纪批判现实主义文学1、裴多菲(匈牙利):《民族之歌》《自由与爱情》《我的泪》《雪地光滑,雪橇疾驶》《夜》《给茹日卡》《太阳的婚后生活》《我宁愿是》《我的心呀,你孤独的笼中鸟》《眼睛呀,你万能的眼》《落吧,落吧,落吧》《来吧,春天,来吧!》《谎言》《我枉然等待吗》《缝纫姑娘》《啊,你美丽的边疆姑娘》《你建造起我心灵的新世界》《我曾经在她身旁》《我的爱情在增长》《你不要判断》《你常常来到我的梦中》《风暴静息了》《永远没有那样的恋人》《每一朵花》《火》《我旅行在大草原上》《你嫁给我吗》《大海沸腾了》四、20世纪后期象征主义文学1、艾略特(英):《荒原》《烧毁的诺顿》《东科克》《干燥的萨尔维吉斯》《J·阿尔弗雷德·普罗弗洛克的情歌》《眼睛,我曾在最后一刻的泪光中看见你》《风在四点骤然刮起》《空心人》《小吉丁》2、叶芝(爱尔兰):《湖心岛茵尼斯弗利岛》《当你老了》《柯尔庄园的天鹅》《基督重临》《丽达与天鹅》《在本布尔山下》《一九一六年复活节》《思想的气球》《圣徒和驼子》《驶向拜占庭》《在学童中间》《旋转》《我的书本去的地方》《天青石雕》《他讲着绝伦的美》《那丧失的东西》《秘密的玫瑰》《另外的面孔》《寒冷的天穹》《词语》《长脚蚊》《白鸟》《致他的心,叫它别害怕》《箭》《印度人的恋歌》《随时间而来的真理》《一位友人的疾病》《人随岁月长进》3、庞德(美):《在地铁车站》《合同》《舞姿》《少女》《为选择墓地而作的颂诗》《普罗旺斯晨歌》《咏叹调》《白罂粟使者》《诗章第49号》《扇诗》五、20世纪现实主义文学1、马雅可夫斯基(俄):《晨》《致俄罗斯》《把未来揪出来!》《最好的诗》《赠耐特同志——船和人》《开会迷》2、叶赛宁(俄):《失去的东西永不复归》《拉起红色的手风琴》《再见吧,我的朋友,再见》《可爱的家乡啊》《我辞别了我出生的屋子》《我不叹惋、呼唤和哭泣》。

惠特曼与狄金森

爱米莉·狄金森在诗歌的形式上,一反传统的格律诗,转而寻求适合表达自己理念和感情的方式,并着重内心探索。狄金森常常捕捉一瞬间的思想,描绘稍纵即逝的景物,促使人们把眼光从身边的琐事移开,注视自然,从而睿悟出人生的隐秘。她强调直觉,强调强烈、瞬间的感官反应,强调意象。狄金森的诗歌内容广泛,主要围绕死亡、永恒、爱情、自然等传统文学主题,表现其对灵魂深处的内省探求,并以其风格独特而著称,备受关注的是她诗中大量地使用意象和“迂回”策略。她甚至被称作一个“谜”一样的人。长期以来对爱米莉·狄金森诗歌的研究成为国内外文学批评家的“热点”所在,因此也出现了对其诗歌主题的不同诠释。

在艺术上,惠特曼的诗歌是不精致的,甚至可以说是粗糙的,随意的。就像一股山洪,从山上跌跌撞撞的滚下来。但正是这种不精致的诗歌,在非常广泛的层面上引起了美国各个阶层的人的共鸣。

这里面一种非常年轻的感觉,正因为年轻,所以对古老的英国诗歌的贵族传统就是一种反叛。

这是典型的平民诗——年轻、自由,无所顾忌地歌唱。你们想一想,从前在贵族沙龙中吟诵、品唱,可是等到惠特曼出来了,工厂的工人、田间的农夫,白人、黑人,都可以吟唱他的诗歌。可以说这是一次诗的解放,是英语文学中的一次诗的解放。

母亲或年轻的妻子在工作时,或者姑娘在缝纫或洗衣裳时甜美地唱着的歌,

每个人都唱着属于他或她而不属于任何其他人的歌,

白天唱着属于白天的歌——晚上这一群体格健壮、友好相处的年轻小伙子,

就放开嗓子唱起他们那雄伟而又悦耳的歌。

(邹绛译)

《芦笛集》是后来增订的表达同性爱恋的诗集,不过迫于压力将诗歌中的许多男性称谓改成了女性。惠特曼在《展望民主》中说:“我们虽然还很难定义强烈而宜人的同志之爱,即男人间的感情依偎,但这种情爱却贯穿着救世原则,而这种原则并不以时空的转换而有所改变。当这种情爱发展成熟,深如人心时,一个民族充满希望与安乐的未来已经到来。”

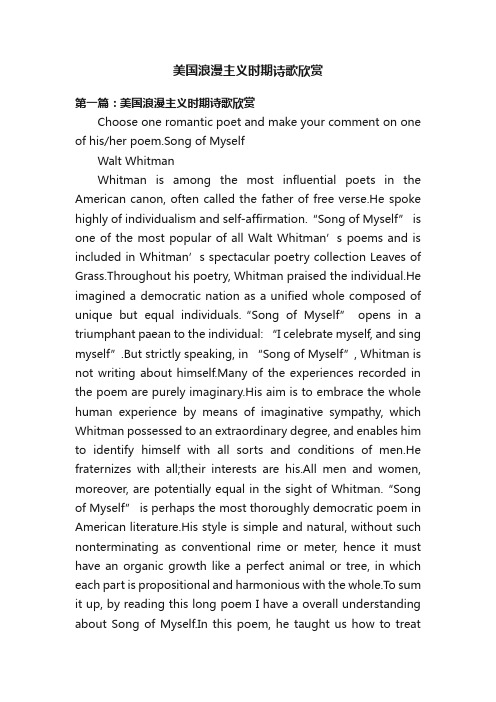

美国浪漫主义时期诗歌欣赏

美国浪漫主义时期诗歌欣赏第一篇:美国浪漫主义时期诗歌欣赏Choose one romantic poet and make your comment on one of his/her poem.Song of MyselfWalt WhitmanWhitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse.He spoke highly of individualism and self-affirmation.“Song of Myself” is one of the most popular of all Walt Whitman’s poems and is included in Whitman’s spectacular poetry collection Leaves of Grass.Throughout his poetry, Whitman praised the individual.He imagined a democratic nation as a unified whole composed of unique but equal individuals.“Song of Myself” opens in a triumphant paean to the individual: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself”.But strictly speaking, in “Song of Myself”, Whitman is not writing about himself.Many of the experiences recorded in the poem are purely imaginary.His aim is to embrace the whole human experience by means of imaginative sympathy, which Whitman possessed to an extraordinary degree, and enables him to identify himself with all sorts and conditions of men.He fraternizes with all;their interests are his.All men and women, moreover, are potentially equal in the sight of Whitman.“Song of Myself” is perhaps the most thorou ghly democratic poem in American literature.His style is simple and natural, without such nonterminating as conventional rime or meter, hence it must have an organic growth like a perfect animal or tree, in which each part is propositional and harmonious with the whole.To sum it up, by reading this long poem I have a overall understanding about Song of Myself.In this poem, he taught us how to treatpeople equally, how to respect nature and ourselves, and that we should always be optimistic about life, both current and future, no matter what the outside world is, just believe in ourselves.专业:英语专业学号:B12123104姓名:王利莹第二篇:美国浪漫主义时期文学家及其作品美国浪漫主义时期文学家及其作品华盛顿·欧文(Washington Irving,1783年-1859年),19世纪美国最著名的作家,号称美国文学之父。

19外国诗两首

未选择的路

弗罗斯特

The Road Not Taken

ROBERT FROST

1 Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

3 And both that morning equallylay

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth. 2 Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same.

If by Life You Were Deceived

If by life you were deceived, Don't be dismal,don't be wild! In the day of grief,be mild: Merry days will come,believe. Heart is living in tomorrow; Present is dejected here: In a moment,passes sorrow; That which passes will be dear.

(陆游)

其实世上本没有路,走的人多了,也便成了路。

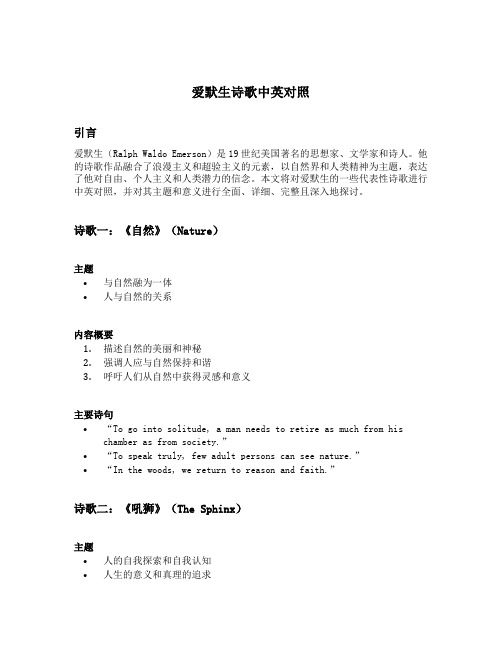

爱默生诗歌中英对照

爱默生诗歌中英对照引言爱默生(Ralph Waldo Emerson)是19世纪美国著名的思想家、文学家和诗人。

他的诗歌作品融合了浪漫主义和超验主义的元素,以自然界和人类精神为主题,表达了他对自由、个人主义和人类潜力的信念。

本文将对爱默生的一些代表性诗歌进行中英对照,并对其主题和意义进行全面、详细、完整且深入地探讨。

诗歌一:《自然》(Nature)主题•与自然融为一体•人与自然的关系内容概要1.描述自然的美丽和神秘2.强调人应与自然保持和谐3.呼吁人们从自然中获得灵感和意义主要诗句•“To go into solitude, a man needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society.”•“To speak truly, few adult persons can see nature.”•“In the woods, we return to reason and faith.”诗歌二:《吼狮》(The Sphinx)主题•人的自我探索和自我认知•人生的意义和真理的追求内容概要1.以古埃及神话形象来探索人的内心世界2.推动读者思考关于生命和人类经验的深层问题3.引导人们寻找自我认知和个人成长的路径主要诗句•“The Sphinx is drowsy.”•“She has no discoverable right to existence.”•“Very unwillingly would it be wooed back to its captivity.”诗歌三:《独立宣言》(The Concord Hymn)主题•爱国主义和自由精神•个人的力量和创造力内容概要1.纪念美国独立战争中的列克星敦和康科德战役2.强调自由、勇气和牺牲精神的重要性3.鼓励个人追求和实现自己的理想和价值主要诗句•“By the rude bridge that arched the flood, their flag to April’s breeze unfurled.”•“Spirit, that made those heroes dare to die.”•“Here once the embattled farmers stood and fired the shot heard round the world.”结论通过对爱默生的诗歌进行中英对照分析,我们可以看到他对自然、人类经验、自我认知和自由精神等主题的关注。

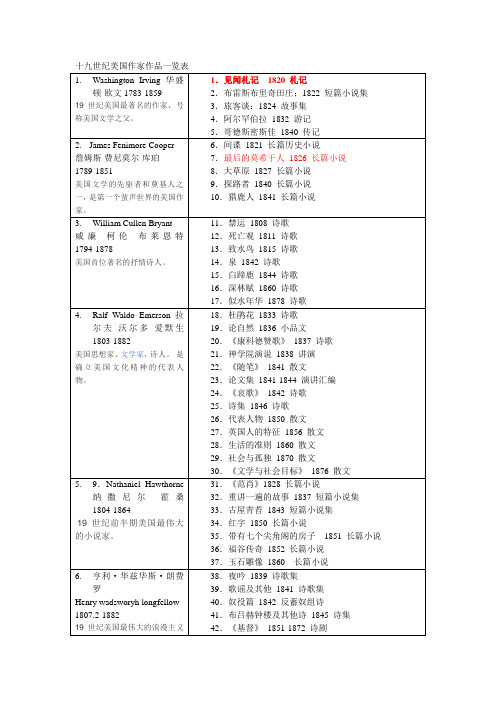

十九世纪美国作家作品一览表

42.《基督》1851-1872诗剧

43.海华沙之歌1855诗歌

44.迈尔斯·斯坦狄什的求婚1858叙事长诗

7.John Greenleaf Whittier约翰·格林里夫·惠蒂埃1807.12-1893

深受英国文学尤其是苏格兰诗人彭斯的影响

45.废奴问题1838诗集

100.败坏了哈德莱堡的人1900中篇小说

16.Francis Bret Harte弗朗西斯·布勒特·哈特1836-1902

小说家,美国西部文学的代表作家。

101.咆哮营的幸运儿1868短篇小说

102.扑克滩的流浪者1870短篇小说

17.20、William Dean Howells威廉·迪安·豪威尔斯

141.中部边地农家子1917自传

24.Edith Wharton伊迪丝·华顿1862.1-1937

美国女作家,一生著作颇丰。

142.高尚的嗜好1899短篇小说集

143.《抉择之谷》1902长篇小说

144.《圣殿》1903中篇小说

145.欢乐之家1905长篇小说

146.纯真年代1920长篇小说

25.O·Henry欧·享利(William Sidney Porter)1862.9-1910

160.克雷格上尉1902诗体小说

161.《墨林》1917长篇叙事诗

162.朗斯洛1920长篇叙事诗

163.特里斯丹1927长篇叙事诗

164.天边人影1916诗集

28.Frank Norris弗兰克·诺里斯1870-1902

165.茱蒂夫人号上的莫兰1898短篇小说

166.麦克提格1899短篇小说

167.章鱼1901短篇小说

19世纪美国浪漫主义文学

朝着理想的方向自信地勇往 直前,过你想过的 生活。

如果我真的对云说话,你千万不要见怪。 城市是一个几百万人一起孤独地生活的地方。

大多数人在安静的绝望中生活,当他们进 入坟墓时,他们的歌还没有唱出来。

你们必须努力寻找自己的声音,因为你越迟 开始寻找,找到的可能性就越小。

活过每一个季节;呼吸空气,喝水,品尝水 果,让自己感受它们对你的影响。

But our love it was stronger by far than the love Of those who were older than we-Of many far wiser than weAnd neither the angels in Heaven above, Nor the demons down under the sea, Can ever dissever my soul from the soul Of the beautiful Annabel Lee: 可我们的爱情远远地胜过 那些年纪长于我们的人—— 那些智慧胜于我们的人—— 无论是天上的天使, 还是海底的恶魔, 都不能将我们的灵魂分离, 我和我美丽的安娜贝尔.李。

创造“自由诗体”

Leaves of Grass

“我相信一片草叶不亚于星球 的运转”

“哪里有土,哪里有水,哪 里就长着草”

1.诗人自身的形象; 2、普通人的象征;

3、美国的象征

主题

自我、创造、民主 歌颂“自我”,赞美人 的力量与活力; 赞颂蓬勃发展的美国, 赞美劳动者的伟大人格 和创业精神:

《瓦尔登湖》至少有五种读法: 1.作为一部自然的书籍;2.作为一部自力更生 、简单生活的指南;3.作为批评现代生活的 一部讽刺作品;4.作为一部文学名著;5.作为 一本神圣的书。

美国现代诗歌(一)

Robert FrostMowing(1915)There was never a sound beside the wood but one, And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground.What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself; Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun, Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound—And that was why it whispered and did not speak.It was no dream of the gift of idle hours,Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf:Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weakTo the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,Not without feeble-pointed spikes of flowers (Pale orchises), and scared a bright green snake. The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows.My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make. After Apple Picking (1915)My long two-pointed ladder’s sticking through a tree Toward heaven still,And there’s a barrel that I didn’t fillBeside it, and there may be two or threeApples I didn’t pick upon some bough.But I am done with apple-picking now.Essence of winter sleep is on the night,The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.I cannot rub the strangeness from my sightI got from looking through a pane of glassI skimmed this morning from the drinking trough And held against the world of hoary grass.It melted, and I let it fall and break.But I was wellUpon my way to sleep before it fell,And I could tellWhat form my dreaming was about to take. Magnified apples appear and disappear,Stem end and blossom end,And every fleck of russet showing clear. My instep arch not only keeps the ache,It keeps the pressure of a ladder-round.I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.And I keep hearing from the cellar binThe rumbling soundOf load on load of apples coming in.For I have had too muchOf apple-picking: I am overtiredOf the great harvest I myself desired.There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall.For allThat struck the earth,No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble, Went surely to the cider-apple heapAs of no worth.One can see what will troubleThis sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is.Were he not gone,The woodchuck could say whether it’s like hisLong sleep, as I describe its coming on,Or just some human sleep.Birches (1916)When I see birches bend to left and rightAcross the line of straighter darker trees,I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay.Ice-storms do that. Often you must have seen them Loaded with ice a sunny winter morningAfter a rain. They click upon themselvesAs the breeze rises, and turn many-coloredAs the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shellsShattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—Such heaps of broken glass to sweep awayYou’d think the inner dome of hea ven had fallen. They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,And they seem not to break; though once they are bowedSo low for long, they never right themselves:You may see their trunks arching in the woodsYears afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.But I was going to say when Truth broke inWith all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm (Now am I free to be poetical?)I should prefer to have some boy bend themAs he went out and in to fetch the cows—Some boy too far from town to learn baseball, Whose only play was what he found himself, Summer or winter, and could play alone.One by one he subdued his father’s treesBy riding them down over and over againUntil he took the stiffness out of them,And not one but hung limp, not one was leftFor him to conquer. He learned all there wasTo learn about not launching out too soonAnd so not carrying the tree awayClear to the ground. He always kept his poiseTo the top branches, climbing carefullyWith the same pains you use to fill a cupUp to the brim, and even above the brim.Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish, Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.So was I once myself a swinger of birches;And so I dream of going back to be.It’s when I’m weary of considerations,And life is too much like a pathless woodWhere your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs Broken across it, and one eye is weepingFrom a twig’s havin g lashed across it open.I’d like to get away from earth awhileAnd then come back to it and begin over.May no fate wilfully misunderstand meAnd half grant what I wish and snatch me away Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more, But dipped its top and set me down again.That would be good both going and coming back. One could do worse than be a swinger of birches. Out out—The buzz-saw snarled and rattled in the yardAnd made dust and dropped stove-length sticks of wood,Sweet-scented stuff when the breeze drew across it. And from there those that lifted eyes could count Five mountain ranges one behind the otherUnder the sunset far into Vermont.And the saw snarled and rattled, snarled and rattled, it ran light, or had to bear a load.And nothing happened: day was all but done.Call it a day, I wish they might have saidTo please the boy by giving him the half hourThat a boy counts so much when saved from work. His sister stood beside them in her apronTo tell them "Supper." At the word, the saw,As if to prove saws knew what supper meant, Leaped out at the boy's hand, or seemed to leap-- He must have given the hand. However it was, Neither refused the meeting. But the hand!The boy's first outcry was a rueful laugh,As he swung toward them holding up the handHalf in appeal, but half as if to keepThe life from spilling. Then the boy saw all--Since he was old enough to know, big boyDoing a man's work, though a child at heart--He saw all spoiled. "Don't let him cut my hand off-- The doctor, when he comes. Don't let him, sister!" So. But the hand was gone already.The doctor put him in the dark of ether.He lay and puffed his lips out with his breath.And then--the watcher at his pulse took fright.No one believed. They listened at his heart.Little--less--nothing!--and that ended it.No more to build on there. And they, since they Were not the one dead, turned to their affairs.Home burialHe saw her from the bottom of the stairsBefore she saw him. She was starting down, Looking back over her shoulder at some fear.She took a doubtful step and then undid itTo raise herself and look again. He spokeAdvancing toward her: 'What is it you seeFrom up there always-for I want to know.'She turned and sank upon her skirts at that,And her face changed from terrified to dull.He said to gain time: 'What is it you see,' Mounting until she cowered under him.'I will find out now-you must tell me, dear.' She, in her place, refused him any helpWith the least stiffening of her neck and silence. She let him look, sure that he wouldn't see,Blind creature; and awhile he didn't see.But at last he murmured, 'Oh,' and again, 'Oh.''What is it - what?' she said.'Just that I see.''You don't,' she challenged. 'Tell me what it is.''The wonder is I didn't see at once.I never noticed it from here before.I must be wonted to it - that's the reason.The little graveyard where my people are!So small the window frames the whole of it.Not so much larger than a bedroom, is it?There are three stones of slate and one of marble, Broad-shouldered little slabs there in the sunlight On the sidehill. We haven't to mind those.But I understand: it is not the stones,But the child's mound''Don't, don't, don't, don't,' she cried.She withdrew shrinking from beneath his arm That rested on the bannister, and slid downstairs; And turned on him with such a daunting look, He said twice over before he knew himself:'Can't a man speak of his own child he's lost?''Not you! Oh, where's my hat? Oh, I don't need it!I must get out of here. I must get air.I don't know rightly whether any man can.''Amy! Don't go to someone else this time. Listen to me. I won't come down the stairs.'He sat and fixed his chin between his fists.'There's something I should like to ask you, dear.' 'You don't know how to ask it.''Help me, then.'Her fingers moved the latch for all reply.'My words are nearly always an offense.I don't know how to speak of anythingSo as to please you. But I might be taughtI should suppose. I can't say I see how.A man must partly give up being a manWith women-folk. We could have some arrangement By which I'd bind myself to keep hands off Anything special you're a-mind to name.Though I don't like such things 'twixt those that love. Two that don't love can't live together without them. But two that do can't live together with them.'She moved the latch a little. 'Don't-don't go.Don't carry it to someone else this time.Tell me about it if it's something human.Let me into your grief. I'm not so muchUnlike other folks as your standing thereApart would make me out. Give me my chance.I do think, though, you overdo it a little.What was it brought you up to think it the thingTo take your mother-loss of a first childSo inconsolably-in the face of love.You'd think his memory might be satisfied''There you go sneering now!''I'm not, I'm not!You make me angry. I'll come down to you.God, what a woman! And it's come to this,A man can't speak of his own child that's dead.''You can't because you don't know how to speak.If you had any feelings, you that dugWith your own hand - how could you? his little grave;I saw you from that very window there,Making the gravel leap and leap in air,Leap up, like that, like that, and land so lightlyAnd roll back down the mound beside the hole.I thought, Who is that man? I didn't know you. And I crept down the stairs and up the stairsTo look again, and still your spade kept lifting. Then you came in. I heard your rumbling voice Out in the kitchen, and I don't know why,But I went near to see with my own eyes.You could sit there with the stains on your shoes Of the fresh earth from your own baby's grave And talk about your everyday concerns.You had stood the spade up against the wall Outside there in the entry, for I saw it.''I shall laugh the worst laugh I ever laughed.I'm cursed. God, if I don't believe I'm cursed.''I can repeat the very words you were saying. "Three foggy mornings and one rainy dayWill rot the best birch fence a man can build." Think of it, talk like that at such a time!What had how long it takes a birch to rotTo do with what was in the darkened parlor.You couldn't care! The nearest friends can go With anyone to death, comes so far shortThey might as well not try to go at all.No, from the time when one is sick to death,One is alone, and he dies more alone.Friends make pretense of following to the grave, But before one is in it, their minds are turnedAnd making the best of their way back to lifeAnd living people, and things they understand. But the world's evil. I won't have grief soIf I can change it. Oh, I won't, I won't!''There, you have said it all and you feel better. You won't go now. You're crying. Close the door. The heart's gone out of it: why keep it up.Amy! There's someone coming down the road!''You - oh, you think the talk is all. I must go Somewhere out of this house. How can I make you''If-you-do!' She was opening the door wider.'Where do you mean to go? First tell me that.I'll follow and bring you back by force. I will!' The Road Not Taken(1920)Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel bothAnd be one traveler, long I stoodAnd looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth;Then took the other, as just as fair,And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same,And both that morning equally layIn leaves no step had trodden black. Oh, I kept the first for another day!Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence:Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by,And that has made all the difference.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Significant Form, Style, or Artistic Conventions

Longfellow’s poems are not only accessible in their meaning, but they are also highly regular in their form. It is very simple to teach metrics with Longfellow because he provides easy and memorable examples of so many metrical schemes. These can be present end in connection chit Longfellow’s personal history, for he is of course an academic poet, and as such a poet writing often self-consciously a learned perspective. Thus, nothing with him seems wholly spontaneous or accidental.

The Song of Hiawatha (epic poem) (1855) 《海华沙之歌》

His works:

A Psalm of life 《人生礼赞》 Voices of the Night 《夜吟》 Hymn to the night 《夜的赞歌》

The Beleaguered City 《群星之光》

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal; Dust thou art, to dust returns,

人生是实在的!人生是热烈的!

人生的目标决不是坟墓; 你是尘土,应归于尘土。

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow, Is our destined end or way; But to act, that each to-morrow Find us farther than to-day.

此话指的并不是我们的精神。

我们的归宿并不是快乐, 也不是悲伤, 实干,才是我们的道路。 每天不断前进,蒸蒸蒸日上。

A Psalm of Life

• It was first published in Voice of the Night in the September edition of New York Monthly in 1839. It is very influential in China, because it is said to be the first English poem translated into . • The poem was written in 1838 when Longfellow was struck with great dismay; his wife died in 1835, and his courtship of a young woman was unrequited. However, despite all the frustrations, Longfellow tried to encourage himself by writing a piece of optimistic work.

A Psalm of Life

• The relationship of life and death is a constant theme for poets. Longfellow expresses his pertinent interpretation to warn us that though life is hard and everybody must die, time and life is short, yet, human beings ought to be bold―to act,‖ to face the reality straightly so as to make otherwise meaningless life significant.

十九世纪美国浪漫主义文学

(1800——1865)

美国浪漫主义文学的特点: 1. 强烈的主观色彩,偏爱表现主观思想,注重抒发个人的感受 和体验,重主观、轻客观和重自我表现,轻客观模仿。 2. 喜欢描写和歌颂大自然(尤为突出)作者们喜欢将自己的理 解人物置身于淳朴宁静的大自然中,衬托现实深灰的丑恶及 自身理解的美好。 3. 重视中世纪民间文学,想想比较丰富,感情真挚,表达自由, 语言朴素自然 。 4. 注重艺术效果:对比夸张、人物形象的超凡性。

Introduction His life experience His major works His writing style

Introduction

• Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807

– March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. • Longfellow predominantly wrote lyric poems which are known for their musicality and which often presented stories of mythology and legend.

19th Century American Poets

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882)

Edgar Allan Poe) (1809-1849)

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

• 第一,二节,针对“人生如梦”的颓废论调,开 宗明义地指出“人生是实在的,人生不是虚无”。 第三,四,五,六节进一步指出,既然生活不是 梦,那就要抓住现在去实干,去行动。第七,八 两节以伟人的榜样来激励人们,要在”时间的沙 滩上”留下脚印,以给后来者以鼓舞,最后一节 以更为激昂的声调总结全诗,首尾呼应,在“不 断去收获,不断去追求” 的强音中结束全诗。 • 本诗四句一节,共计三十六句,分为九节。上一 节食下一节内容的铺垫,每一节内容都有层层递 进的趋势,像一只无形而又强有力的手,一步步 把我们推向思想的高潮。

• He became the most popular American poet of his day and also had success overseas. He has been criticized, however, for imitating European styles and writing specifically for the masses.

Appreciation of A Psalm of Life

• A Psalm of Life which is wri Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is a lyric poem. It reveals the optimistic theme-time is fleeting, act in the living present. The poem appeals to the readers’ eyes, ears, minds and emotions and shows the poet’s richly endowed talents for both aesthetics and language manipulation as well.

Grave of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

His major works:

Voices of the Night (1839) 《夜吟》 Ballads and Other Poems (1841) 《歌谣及其他》 Evangeline: A Tale of Acadia (epic poem) (1847) 《伊凡杰林》

He wrote a poem for her called ―Footsteps of Angels‖ which was published in 1839.

He remarried in 1843 with Fanny Appleton. She died in 1861 from a tragic death, she was burned to death. Later Henry died in March 24, 1882 at Cambridge, Massachusetts.

• Longfellow is generally regarded as the most distinguished poet the country had produced.

His life experience:

Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, then part of Massachusetts, and studied at Bowdoin College. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was enrolled in a dame school at the age of three and by age six was enrolled at the private Portland Academy. In his years there, he earned a reputation as being very studious and became fluent in Latin. In the fall of 1822, the 15-year old Longfellow enrolled at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, alongside his brother Stephen. There, Longfellow met Nathaniel Hawthorne, who would later become his lifelong friend. On September 14, 1831, Longfellow married Mary Storer Potter, a childhood friend from Portland. While in Europe he studied Swedish, dutch, and French. In 1835 Mary died after only four years of marriage in Rotterdam.