经典英文短篇小说 (48)

英语短篇小说朗诵欣赏

英语短篇小说朗诵欣赏

英语短篇小说是一种精彩的文学形式,它以简短的篇幅讲述一个完整的故事,往往给人留下深刻的印象。

下面是几篇值得欣赏的英语短篇小说,希望能够为您带来一些喜悦和启发。

1. "The Gift of the Magi" by O. Henry

这是一篇经典的英语短篇小说,讲述了一对贫穷夫妇的故事。

在圣诞节即将来临时,他们为了给对方买礼物,各自做出了牺牲。

最终,他们明白到真正的礼物是彼此的爱。

这个故事温暖人心,给人留下了深刻的思考。

2. "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson

这是一篇令人瞩目的英语短篇小说,讲述了一个平凡小镇举行的抽签抽奖活动。

然而,这个抽奖活动的结果却令人震惊和恐惧。

这个故事探讨了社会的黑暗面和人性的复杂性,给人以警示。

3. "The Necklace" by Guy de Maupassant

这是一篇经典的法国短篇小说,讲述了一个女人因一条丢失的项链而陷入困境的故事。

通过这个故事,我们能够看到虚荣和自负的危险,以及珍惜现有的幸福的重要性。

4. "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe

这是一篇恐怖的英语短篇小说,讲述了一个疯狂的人因良心的谴责而被逼发疯的故事。

通过一系列紧张的描写,这个故事唤起了读者的疑虑和恐惧,展示了人类内心深处的黑暗面。

以上是几篇值得欣赏的英语短篇小说,每一篇都有其独特的味道和意义。

希望您享受这些故事,并从中获得启迪和欢乐。

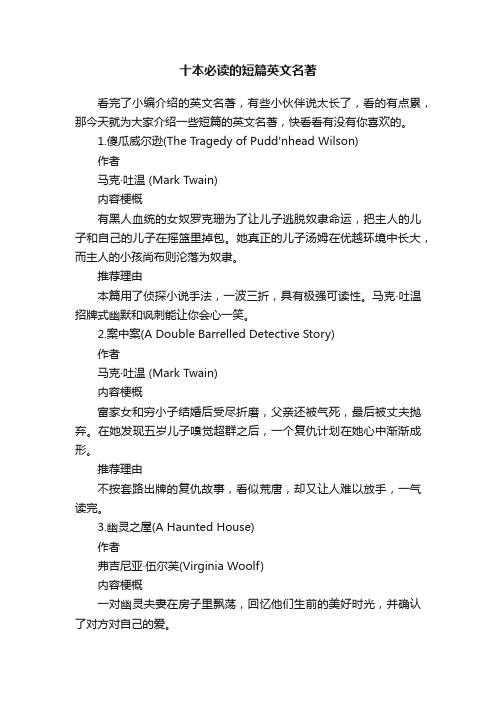

十本必读的短篇英文名著

十本必读的短篇英文名著看完了小编介绍的英文名著,有些小伙伴说太长了,看的有点累,那今天就为大家介绍一些短篇的英文名著,快看看有没有你喜欢的。

1.傻瓜威尔逊(The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson)作者马克·吐温 (Mark Twain)内容梗概有黑人血统的女奴罗克珊为了让儿子逃脱奴隶命运,把主人的儿子和自己的儿子在摇篮里掉包。

她真正的儿子汤姆在优越环境中长大,而主人的小孩尚布则沦落为奴隶。

推荐理由本篇用了侦探小说手法,一波三折,具有极强可读性。

马克·吐温招牌式幽默和讽刺能让你会心一笑。

2.案中案(A Double Barrelled Detective Story)作者马克·吐温 (Mark Twain)内容梗概富家女和穷小子结婚后受尽折磨,父亲还被气死,最后被丈夫抛弃。

在她发现五岁儿子嗅觉超群之后,一个复仇计划在她心中渐渐成形。

推荐理由不按套路出牌的复仇故事,看似荒唐,却又让人难以放手,一气读完。

3.幽灵之屋(A Haunted House)作者弗吉尼亚·伍尔芙(Virginia Woolf)内容梗概一对幽灵夫妻在房子里飘荡,回忆他们生前的美好时光,并确认了对方对自己的爱。

推荐理由虽然是鬼故事,但却十分澄澈美好。

优美的语言具有抚慰人心的力量。

4.一间自己的屋子(A Room of One's Own)作者弗吉尼亚·伍尔芙(Virginia Woolf)内容梗概这本书的内容是伍尔夫在女子学院的两篇讲稿,以“妇女和小说”为主题,通过对女性创作的历史及现状的分析,指出女人应该有勇气有理智地去争取独立的经济力量和社会地位。

推荐理由“当我在我的脑子里搜索的时候,我发现我对于做别人的伴侣,做与别人相等的人,以及去影响这世界为了去达到更高的目的都没有什么高尚的感觉。

我只很简单很平凡地说,成为自己比什么都要紧。

”5.三个陌生人(The Three Strangers)作者托马斯·哈代(Thomas Hardy)内容梗概一个牧羊少年惊恐地睁大了双眼,从他的小棚屋中往外窥视一个女人和情人的幽会。

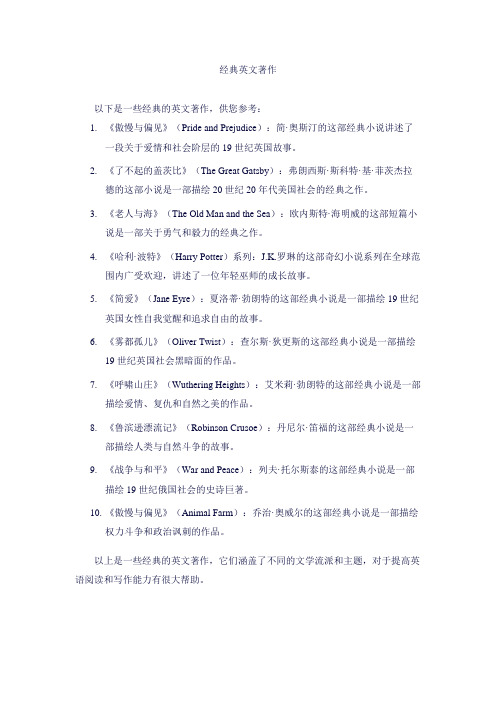

经典英文著作

经典英文著作以下是一些经典的英文著作,供您参考:1.《傲慢与偏见》(Pride and Prejudice):简·奥斯汀的这部经典小说讲述了一段关于爱情和社会阶层的19世纪英国故事。

2.《了不起的盖茨比》(The Great Gatsby):弗朗西斯·斯科特·基·菲茨杰拉德的这部小说是一部描绘20世纪20年代美国社会的经典之作。

3.《老人与海》(The Old Man and the Sea):欧内斯特·海明威的这部短篇小说是一部关于勇气和毅力的经典之作。

4.《哈利·波特》(Harry Potter)系列:J.K.罗琳的这部奇幻小说系列在全球范围内广受欢迎,讲述了一位年轻巫师的成长故事。

5.《简爱》(Jane Eyre):夏洛蒂·勃朗特的这部经典小说是一部描绘19世纪英国女性自我觉醒和追求自由的故事。

6.《雾都孤儿》(Oliver Twist):查尔斯·狄更斯的这部经典小说是一部描绘19世纪英国社会黑暗面的作品。

7.《呼啸山庄》(Wuthering Heights):艾米莉·勃朗特的这部经典小说是一部描绘爱情、复仇和自然之美的作品。

8.《鲁滨逊漂流记》(Robinson Crusoe):丹尼尔·笛福的这部经典小说是一部描绘人类与自然斗争的故事。

9.《战争与和平》(War and Peace):列夫·托尔斯泰的这部经典小说是一部描绘19世纪俄国社会的史诗巨著。

10.《傲慢与偏见》(Animal Farm):乔治·奥威尔的这部经典小说是一部描绘权力斗争和政治讽刺的作品。

以上是一些经典的英文著作,它们涵盖了不同的文学流派和主题,对于提高英语阅读和写作能力有很大帮助。

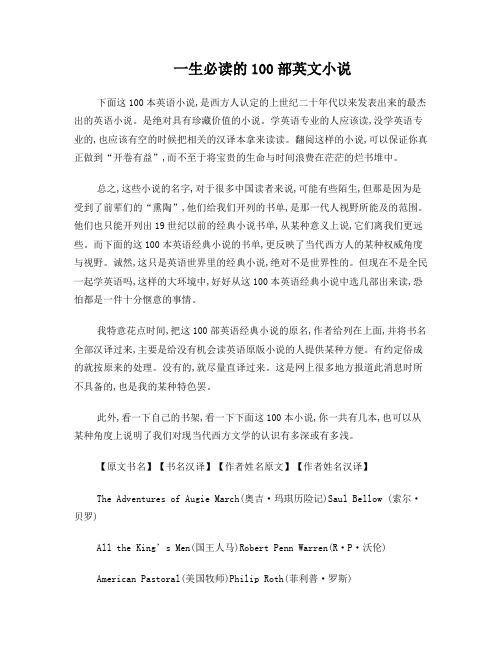

一生必读的100部英文小说

一生必读的100部英文小说下面这100本英语小说,是西方人认定的上世纪二十年代以来发表出来的最杰出的英语小说。

是绝对具有珍藏价值的小说。

学英语专业的人应该读,没学英语专业的,也应该有空的时候把相关的汉译本拿来读读。

翻阅这样的小说,可以保证你真正做到“开卷有益”,而不至于将宝贵的生命与时间浪费在茫茫的烂书堆中。

总之,这些小说的名字,对于很多中国读者来说,可能有些陌生,但那是因为是受到了前辈们的“熏陶”,他们给我们开列的书单,是那一代人视野所能及的范围。

他们也只能开列出19世纪以前的经典小说书单,从某种意义上说,它们离我们更远些。

而下面的这100本英语经典小说的书单,更反映了当代西方人的某种权威角度与视野。

诚然,这只是英语世界里的经典小说,绝对不是世界性的。

但现在不是全民一起学英语吗,这样的大环境中,好好从这100本英语经典小说中选几部出来读,恐怕都是一件十分惬意的事情。

我特意花点时间,把这100部英语经典小说的原名,作者给列在上面,并将书名全部汉译过来,主要是给没有机会读英语原版小说的人提供某种方便。

有约定俗成的就按原来的处理。

没有的,就尽量直译过来。

这是网上很多地方报道此消息时所不具备的,也是我的某种特色罢。

此外,看一下自己的书架,看一下下面这100本小说,你一共有几本,也可以从某种角度上说明了我们对现当代西方文学的认识有多深或有多浅。

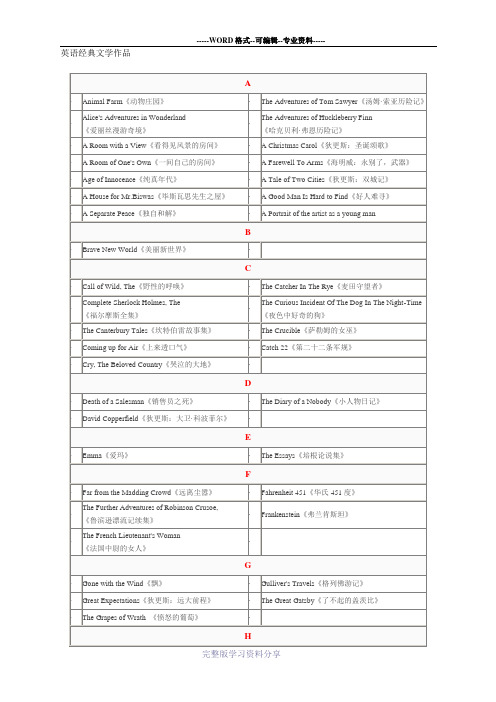

【原文书名】【书名汉译】【作者姓名原文】【作者姓名汉译】The Adventures of Augie March(奥吉·玛琪历险记)Saul Bellow (索尔·贝罗)All the King’s Men(国王人马)Robert Penn Warren(R·P·沃伦)American Pastoral(美国牧师)Philip Roth(菲利普·罗斯)An American Tragedy(美国悲剧)Theodore Dreiser(狄德罗·德莱塞)Animal Farm(动物农场)George Orwell(乔治·奥维尔)Appointment in Samarra(相约萨玛拉)John O’Hara(约翰·奥哈拉)Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret(神哪,您在那里吗?是我,玛格丽特)Judy Blume(朱迪·布罗姆)The Assistant(助手)Bernard Malamud(伯纳德·马拉迈德)At Swim-Two-Birds(双鸟嬉戏池塘边)Flann O’Brien(弗兰·奥伯兰)Atonement(救赎)艾恩·麦克埃文Beloved(宠儿)Toni Morrison(托尼·莫里逊)The Berlin Stories(柏林故事集)Christopher Isherwood(克里斯托夫·埃舍伍德) The Big Sleep(夜长梦多)Raymond Chandler(雷蒙·珊德勒)The Blind Assassin(盲人杀手)Margaret Atwood(玛格丽特·埃特伍德)Blood Meridian(血色子午线)Cormac McCarthy(考麦克·麦卡锡)Brideshead Revisited (旧地重游)Evelyn Waugh (埃菲琳·瓦)The Bridge of San Luis Rey(圣路易雷桥)Thornton Wilder(桑顿·王尔德)Call It Sleep(睡眠)Henry Roth(亨利·罗斯)Catch-22 (第二十二条军规)Joseph Heller(约瑟·海勒)The Catcher in the Rye(麦田守望者)J.D. Salinger(J·D·塞林格)A Clockwork Orange(发条橙子)Anthony Burgess(安东尼·伯格斯)The Confessions of Nat Turner(纳特·特纳的忏悔)William Styron(威廉·斯太龙) The Corrections(纠正)Jonathan Franzen(约那逊·弗兰森)The Crying of Lot 49(拍卖第49号])Thomas Pynchon(托马斯·品钦)A Dance to the Music of Time(随时间音乐起舞)Anthony Powell(安东尼·鲍威) The Day of the Locust(蝗虫肆虐日)Nathanael West(那瑟那尔·威斯特)Death Comes for the Archbishop(大主教之死)Willa Cather(威拉·凯瑟)A Death in the Family(家族成员之死)James Agee(詹姆斯·阿吉)The Death of the Heart(心脏之死)Elizabeth Bowen(伊丽莎白·伯文) Deliverance(释放)James Dickey(詹姆斯·迪克)Dog Soldiers(亡命之徒)Robert Stone(罗伯特·斯通)Falconer(放鹰者)John Cheever(约翰·契佛)The French Lieutenant’s Woman (法国中尉的女人)John Fowles(约翰·弗勒斯) The Golden Notebook(金色笔记)Doris Lessi ng(D·莱辛)Go Tell it on the Mountain(山上高呼)James Baldwin(詹姆斯·鲍德温)Gone With the Wind(飘)Margaret Mitchell(玛格丽特·米切尔)The Grapes of Wrath(愤怒的葡萄)John Steinbeck(约翰·斯坦伯克)Gravity’s Rainbow(引力彩虹)Thomas Pynchon(托马斯·品钦)The Great Gatsby(了不起的盖茨比)F. Scott Fit zgerald(F·斯考特·菲茨杰拉德)A Handful of Dust(一掬尘土)Evelyn Waugh(埃菲琳·瓦)The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter(心是孤独的猎手)Carson McCullers(卡尔逊·迈勒斯) The Heart of the Matter(核心问题)Graham Greene(G·格林)Herzog(赫尔佐格)Saul Bellow(索尔·贝罗)Housekeeping(管家)Marilynne Robinson (玛琳·罗伯逊)A House for Mr. Biswas(毕斯瓦思先生之屋)V.S. Naipaul (V·S·纳保罗)I, Claudius(我,克劳迪斯)Robert Graves(罗伯特·格里夫斯)Infinite Jest(无尽的玩笑)David Foster Wallace(戴维·弗斯特·华莱士)Invisible Man(隐形人)Ralph Ellison(拉尔芙·埃利逊)Light in August(八月之光)William Faulkner(威廉·福克纳)The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe(狮子,女巫和魔衣橱)C.S.Lewis(C·S·Lewis) Lolita(洛丽塔)Vladimir Naboko 弗拉基米尔·那波克Lord of the Flies(蝇王)William Golding 威廉·格尔丁The Lord of the Rings(指环王)by J.R.R. Tolkein (J·R·R·托肯)Loving(爱)Henry Green(亨利·格林)Lucky Jim(幸运的吉姆)Kingsley Amis(金斯利·埃米斯)The Man Who Loved Children (那个喜欢孩子的人)Christina Stead(克里斯蒂·斯太德) Midnight's Children(午夜之子)Salman Rushdie(萨尔曼·拉什迪)Money(金钱)Martin Amis(马丁·埃米斯)The Moviegoer(电影迷)Walker Percy(沃克·泊西)Mrs. Dalloway(达罗薇夫人)Virginia Woolf(芙吉妮亚·伍尔夫)Naked Lunch(裸体午餐)William Burroughs (威廉·伯罗斯)Native Son(土著之子)Richard Wright(理查·莱特)Neuromancer(神经漫游者)William Gibson(威廉·吉普逊)Never Let Me Go(别让我走)Kazuo Ishiguro (卡佐·伊什古罗)1984(一九八四)George Orwell(乔治·奥维尔)On the Road(在路上)by Jack Kerouac(杰克·克鲁亚克)One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest(飞越疯人院)Ken Kesey(肯·克西)The Painted Bird(染色鸟)Jerzy Kosinski(泽西·克金斯基)Pale Fire(幽冥火)Vladimir Nabokov(弗拉基米尔·那巴克夫)A Passage to India(印度之行)E.M. Forster(E·M·弗斯特)Play It As It Lays(顺其自然)Joan Didion(琼·迪丹)Portnoy's Complaint (波特诺的抱怨)Philip Roth(菲利普·罗斯)Possession(占有)A.S. Byatt(A·S·伯亚特)The Power and the Glory(权力与荣耀)Graham Greene(G·格林)The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie(让·布罗迪小姐的巅峰时刻)MurielSpark(莫里·斯巴克) Rabbit, Run(兔子,跑吧)John Updike(约翰·厄普代克) Ragtime(雷格泰姆音乐)E.L. Doctorow(E·L·多克特罗)The Recognitions(辨识)William Gaddis(威廉·格迪斯)Red Harvest(红色收获)Dashiell Hammett (达斯·哈迈特)Revolutionary Road(革命之路)Richard Yates(理查·叶茨)The Sheltering Sky(僻护天空)Paul Bowles(保罗·保尔斯)Slaughterhouse-Five(第五号屠场)Kurt V onnegut(克特·冯尼格特)Snow Crash(雪崩)Neal Stephenson(尼尔·史蒂文森)The Sot-Weed Factor(因素)John Barth(约翰·伯斯)The Sound and the Fury(喧哗与骚动)William Faulkner(威廉·福克纳)The Sportswriter(体育新闻记者)Richard Ford(理查·福特)The Spy Who Came in From the Cold(柏林谍影)John LeCarre(约翰·勒克) The Sun Also Rises(太阳照样升起)Ernest Hemingway(厄内斯特·海明威)Their Eyes Were Watching God(他们仰望上帝)Zora Neale Hurston(佐拉·尼尔·赫斯顿) Things Fall Apart(瓦解)Chinua Achebe(切努瓦·阿切比)To Kill a Mockingbird(杀死一只知更鸟)Harper Lee(哈普·李)To the Lighthouse(到灯塔去)Virginia Woolf(芙吉妮亚·伍尔夫)Tropic of Cancer(北回归线)Henry Miller(亨利·米勒)Ubik(尤比克)Philip K. Dick (菲·K·迪克)Under the Net(网下)Iris Murdoch(埃尔斯·莫多克)Under the V olcano(火山下)Malcolm Lowrey(马尔孔·罗瑞) Watchmen by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons(守夜者)White Noise(白噪音)Don DeLillo(丹·迪里罗)White Teeth(白色的牙齿)Zadie Smith(匝迪·史密斯) Wide Sargasso Sea(野海草之海)Jean Rhys(让·里斯。

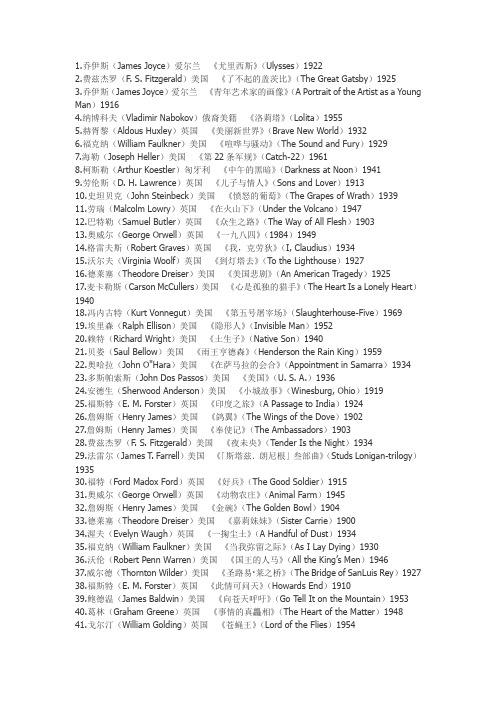

英文小说推荐

1.乔伊斯(James Joyce)爱尔兰《尤里西斯》(Ulysses)19222.费兹杰罗(F. S. Fitzgerald)美国《了不起的盖茨比》(The Great Gatsby)19253.乔伊斯(James Joyce)爱尔兰《青年艺术家的画像》(A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)19164.纳博科夫(Vladimir Nabokov)俄裔美籍《洛莉塔》(Lolita)19555.赫胥黎(Aldous Huxley)英国《美丽新世界》(Brave New World)19326.福克纳(William Faulkner)美国《喧哗与骚动》(The Sound and Fury)19297.海勒(Joseph Heller)美国《第22条军规》(Catch-22)19618.柯斯勒(Arthur Koestler)匈牙利《中午的黑暗》(Darkness at Noon)19419.劳伦斯(D. H. Lawrence)英国《儿子与情人》(Sons and Lover)191310.史坦贝克(John Steinbeck)美国《愤怒的葡萄》(The Grapes of Wrath)193911.劳瑞(Malcolm Lowry)英国《在火山下》(Under the Volcano)194712.巴特勒(Samuel Butler)英国《众生之路》(The Way of All Flesh)190313.奥威尔(George Orwell)英国《一九八四》(1984)194914.格雷夫斯(Robert Graves)英国《我,克劳狄》(I, Claudius)193415.沃尔夫(Virginia Woolf)英国《到灯塔去》(To the Lighthouse)192716.德莱塞(Theodore Dreiser)美国《美国悲剧》(An American Tragedy)192517.麦卡勒斯(Carson McCullers)美国《心是孤独的猎手》(The Heart Is a Lonely Heart)194018.冯内古特(Kurt Vonnegut)美国《第五号屠宰场》(Slaughterhouse-Five)196919.埃里森(Ralph Ellison)美国《隐形人》(Invisible Man)195220.赖特(Richard Wright)美国《土生子》(Native Son)194021.贝娄(Saul Bellow)美国《雨王亨德森》(Henderson the Rain King)195922.奥哈拉(John O"Hara)美国《在萨马拉的会合》(Appointment in Samarra)193423.多斯帕索斯(John Dos Passos)美国《美国》(U. S. A.)193624.安德生(Sherwood Anderson)美国《小城故事》(Winesburg, Ohio)191925.福斯特(E. M. Forster)英国《印度之旅》(A Passage to India)192426.詹姆斯(Henry James)美国《鸽翼》(The Wings of the Dove)190227.詹姆斯(Henry James)美国《奉使记》(The Ambassadors)190328.费兹杰罗(F. S. Fitzgerald)美国《夜未央》(Tender Is the Night)193429.法雷尔(James T. Farrell)美国《「斯塔兹.朗尼根」叁部曲》(Studs Lonigan-trilogy)193530.福特(Ford Madox Ford)英国《好兵》(The Good Soldier)191531.奥威尔(George Orwell)英国《动物农庄》(Animal Farm)194532.詹姆斯(Henry James)美国《金碗》(The Golden Bowl)190433.德莱塞(Theodore Dreiser)美国《嘉莉妹妹》(Sister Carrie)190034.渥夫(Evelyn Waugh)英国《一掬尘土》(A Handful of Dust)193435.福克纳(William Faulkner)美国《当我弥留之际》(As I Lay Dying)193036.沃伦(Robert Penn Warren)美国《国王的人马》(All the King’s Men)194637.威尔德(Thornton Wilder)美国《圣路易·莱之桥》(The Bridge of SanLuis Rey)192738.福斯特(E. M. Forster)英国《此情可问天》(Howards End)191039.鲍德温(James Baldwin)美国《向苍天呼吁》(Go Tell It on the Mountain)195340.葛林(Graham Greene)英国《事情的真龘相》(The Heart of the Matter)194841.戈尔汀(William Golding)英国《苍蝇王》(Lord of the Flies)195442.迪基(James Dickey)美国《解救》(Deliverance)197043.鲍威尔(Anthony Powell)英国《与时代合拍的舞蹈》(A Dance to the Music of Time)197544.赫胥黎(Aldous Huxley)英国《针锋相对》(Point Counter Point)192845.海明威(Ernest Hemingway)美国《太阳照样升起》(The Sun Also Rise)192646.康拉德(Joseph Conrad)英国《特务》(The Secret Agent)190747.康拉德(Joseph Conrad)英国《诺斯特罗莫》(Nostromo)190448.劳伦斯(D. H. Lawrence)英国《彩虹》(Rainbow)191549.劳伦斯(D. H. Lawrence)英国《恋爱中的女人》(Women in Love)192050.米勒(Henry Miller)美国《北回归线》(Tropic of Cancer)193451.梅勒(Norman Mailer)美国《裸者和死者》(The Naked and Dead)194852.罗斯(Philp Roth)美国《波特诺伊的抱怨》(Portnoy"s Complaint)196953.纳博科夫(Vladimir Nabokov)俄裔美籍《苍白的火》(Pale Fire)196254.福克纳(William Faulkner)美国《八月之光》(Light in August)193255.凯鲁亚克(Jack Kerouac)美国《在路上》(On the Road)195756.汉密特(Dashiell Hammett)美国《马尔他之鹰》(The Maltese Falcon)193057.福特(Ford Madox Ford)英国《行进的目的》(Parade’s End)192858.华顿(Edith Wharton)美国《纯真年代》(The Age of Innocence)192059.毕尔邦(Max Beerbohm)英国《朱莱卡.多卜生》(Zuleika Dobson)191160.柏西(Walker Percy)美国《热爱电影的人》(The Moviegoer)196161.凯赛(Willa Cather)美国《总主教之死》(Death Comes to Archbishop)192762.锺斯(James Jones)美国《乱世忠魂》(From Here to Eternity)195163.奇佛(John Cheever)美国《丰普肖特纪事》(The Wapshot Chronicles)195764.沙林杰(J. D. Salinger)美国《麦田里的守望者》(The Catcher in the Rye)195165.柏基斯(Anthony Burgess)英国《发条橙》(A Clockwork Orange)196266.毛姆(W. Somerset Maugham)英国《人性枷锁》(Of Human Bondage)191567.康拉德(Joseph Conrad)英国《黑暗之心》(Heart of Darkness)190268.刘易斯(Sinclair Lewis)美国《大街》(Main Street)192069.华顿(Edith Wharton)美国《欢乐之家》(The House of Mirth)190570.达雷尔(Lawrence Durrell)英国《亚历山大四部曲》(The Alexandraia Quartet)196071.休斯(Richard Hughes)英国《牙买加的风》(A High Wind in Jamaica)192972.耐波耳(V. S. Naipaul)千里达《毕斯瓦思先生之屋》(A House for Mr. Biswas)196173.威斯特(Nathaniel West)美国《蝗虫的日子》(The Day of the Locust)193974.海明威(Ernest Hemingway)美国《永别了,武器》(A Farewell to Arms)192975.渥夫(Evelyn Waugh)英国《独家新闻》(Scoop)193876.丝帕克(Muriel Spark)英国《琼.布罗迪小姐的青春》(The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie)196177.乔伊斯(James Joyce)爱尔兰《为芬尼根守灵》(Finnegans Wake)193978.吉卜林(Rudyard Kipling)英国《金姆》(Kim)190179.福斯特(E. M. Forster)英国《窗外有蓝天》(A Room with a View)190880.渥夫(Evelyn Waugh)英国《梦断白庄》(Bride Shead Revisited)194581.贝娄(Saul Bellow)美国《奥吉·马奇正传》(The Adventures of Augie March)197182.史达格纳(Wallace Stegner)美国《安眠的天使》(Angle of Repose)197183.耐波耳(V. S. Naipaul)千里达《河曲》(A Bend in the River)197984.鲍恩(Elizabeth Bowen)英国《心之死》(The Death of the Heart)193885.康拉德(Joseph Conrad)英国《吉姆爷》(Lord Jim)190086.达特罗(E. L. Doctorow)美国《拉格泰姆》(Ragtime)197587.贝内特(Arnold Bennett)英国《老妇人的故事》(The Old Wives" Tale)190888.伦敦(Jack London)英国《野性的呼唤》(The Call of the Wild)190389.格林(Henry Green)英国《爱》(Loving)194590.鲁西迪(Salman Rushdie)(印裔英籍)《午夜的孩子们》(Midnight’s Children)198191.考德威尔(Erskine Caldwell)美国《菸草路》(Tobacco Road)193292.甘耐第(William Kennedy)美国《紫苑草》(Ironweed)198393.佛勒斯(John Fowles)英国《占星家》(The Magus)196694.里丝(Jean Rhys)英国《辽阔的藻海》(Wide Sargasso)196695.默多克(Iris Murdoch)英国《在网下》(Under the Net)195496.斯泰伦(William Styron)美国《苏菲的抉择》(Sophie’s Choice)197997.鲍尔斯(Paul Bowles)美国《遮蔽的天空》(The Sheltering Sky)194998.凯恩(James M. Cain)美国《邮差总按两次铃》(The Postman Always Rings Twice)193499.唐利维(J. P. Donleavy)美国《眼线》(The Ginger Man)1955100.塔金顿(Booth Tarkington)美国《伟大的安伯森斯》(The Magnificent Ambersons)1918。

英语经典文学作品

Tales From Shakespeare《莎士比亚故事集》

·

Tess of the d’Urbervilles《德伯家的苔丝》

U

·

Uncle Tom's Cabin《汤姆叔叔的小屋》

·

Ulysses《尤利西斯》

V

·

Vanity Fair《名利场》

·

W

·

Wuthering Heights《呼啸山庄》

英语经典文学作品

A

·

Animal Farm《动物庄园》

·

TheAdventures of Tom Sawyer《汤姆·索亚历险记》

·

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

《爱丽丝漫游奇境》

·

TheAdventures of Huckleberry Finn

《哈克贝利·弗恩历险记》

·

The Diary of a Nobody《小人物日记》

·

David Copperfield《狄更斯:大卫·科波菲尔》

·

E

·

Emma《爱玛》

·

TheEssays《培根论说集》

F

·

Far from the Madding Crowd《远离尘嚣》

·

Fahrenheit 451《华氏451度》

·

TheFurther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe,

K

·

Kidnapped《绑架》

·

L

·

Lolita《洛丽塔》

·

Lord Of The Flies《童年无悔》

·

Lion In Winter, The《冬狮》

经典英文短篇小说

A Pair of Silk Stockings Cousin Tribulation's Story How the Camel Got His Hump RegretRikki-Tikki-TaviThe Brave Tin SoldierThe CactusThe Haunted MindThe Story of An HourThe Tale of Peter RabbitA Pair of Silk Stockingsby Kate ChopinLittle Mrs. Sommers one day found herself the unexpected possessor of fifteen dollars. It seemed to her a very large amount of money, and the way in which it stuffed and bulged her worn old porte-monnaie gave her a feeling of importance such as she had not enjoyed for years.The question of investment was one that occupied her greatly. For a day or two she walked about apparently in a dreamy state, but really absorbed in speculation and calculation. She did not wish to act hastily, to do anything she might afterward regret. But it was during the still hours of the night when she lay awake revolving plans in her mind that she seemed to see her way clearly toward a proper and judicious use of the money.A dollar or two should be added to the price usually paid for Janie's shoes, which would insure their lasting an appreciable time longer than they usually did. She would buy so and so many yards of percale for new shirt waists for the boys and Janie and Mag. She had intended to make the old ones do by skilful patching. Mag should have another gown. She had seen some beautiful patterns, veritable bargains in the shop windows. And still there would be left enough for new stockings--two pairs apiece--and what darning that would save for a while! She would get caps for the boys and sailor-hats for the girls. The vision of her little brood looking fresh and dainty and new for once in their lives excited her and made her restless and wakeful with anticipation.The neighbors sometimes talked of certain "better days" that little Mrs. Sommers had known before she had ever thought of being Mrs. Sommers. She herself indulged in no such morbid retrospection. She had no time--no second of time to devote to the past. The needs of the present absorbed her every faculty. A vision of the future like some dim, gaunt monster sometimes appalled her, but luckily tomorrow never comes.Mrs. Sommers was one who knew the value of bargains; who could stand for hours making her way inch by inch toward the desired object that was selling below cost. She could elbow her way if need be; she had learned to clutch a piece of goods and hold it and stick to it with persistence and determination till her turn came to be served, no matter when it came.But that day she was a little faint and tired. She had swallowed a light luncheon--no! when she came to think of it, between getting the children fed and the place righted, and preparing herself for the shopping bout, she had actually forgotten to eat any luncheon at all!She sat herself upon a revolving stool before a counter that was comparatively deserted, trying to gather strength and courage to charge through an eager multitude that was besieging breastworks of shirting and figured lawn. An all-gone limp feeling had come over her and she rested her hand aimlessly upon the counter. She wore no gloves. By degrees she grew aware that her hand had encountered something very soothing, very pleasant to touch. She looked down to see that her hand lay upon a pile of silk stockings. A placard nearby announced that they had been reduced in price from two dollars and fifty cents to one dollar and ninety-eight cents; and a young girl who stood behind the counter asked her if she wished to examine their line of silk hosiery. She smiled, just as if she had been asked to inspect a tiara of diamonds with the ultimate view of purchasing it. But she went on feeling the soft, sheeny luxurious things--with both hands now, holding them up to see them glisten, and to feel them glide serpent-like through her fingers.Two hectic blotches came suddenly into her pale cheeks. She looked up at the girl."Do you think there are any eights-and-a-half among these?"There were any number of eights-and-a-half. In fact, there were more of that size than any other. Here was a light-blue pair; there were some lavender, some all black and various shades of tan and gray. Mrs. Sommers selected a black pair and looked at them very long and closely. She pretended to be examining their texture, which the clerk assured her was excellent."A dollar and ninety-eight cents," she mused aloud. "Well, I'll take this pair." She handed the girl a five-dollar bill and waited for her change and for her parcel. What a very small parcel it was! It seemed lost in the depths of her shabby old shopping-bag.Mrs. Sommers after that did not move in the direction of the bargain counter. She took the elevator, which carried her to an upper floor into the region of the ladies' waiting-rooms. Here, in a retired corner, she exchanged her cotton stockings for the new silk ones which she had just bought. She was not going through any acute mental process or reasoning with herself, nor was she striving to explain to her satisfaction the motive of her action. She was not thinking at all. She seemed for the time to be taking a rest from that laborious and fatiguing function and to have abandoned herself to some mechanical impulse that directed her actions and freed her of responsibility.How good was the touch of the raw silk to her flesh! She felt like lying back in the cushioned chair and revelling for a while in the luxury of it. She did for a little while. Then she replaced her shoes, rolled the cotton stockings together and thrust them into her bag. After doing this she crossed straight over to the shoe department and took her seat to be fitted.She was fastidious. The clerk could not make her out; he could not reconcile her shoes with her stockings, and she was not too easily pleased. She held back her skirts and turned her feet one way and her head another way as she glanced down at the polished, pointed-tipped boots. Her foot and ankle looked very pretty. She could not realize that they belonged to her and were a part of herself. She wanted an excellent and stylish fit, she told the young fellow who served her, and she did not mind the difference of a dollar or two more in the price so long as she got what she desired.It was a long time since Mrs. Sommers had been fitted with gloves. On rare occasions when she had bought a pair they were always "bargains," so cheap that it would have been preposterous and unreasonable to have expected them to be fitted to the hand.Now she rested her elbow on the cushion of the glove counter, and a pretty, pleasant young creature, delicate and deft of touch, drew a long-wristed "kid" over Mrs. Sommers's hand. She smoothed it down over the wrist and buttoned it neatly, and both lost themselves for a second or two in admiring contemplation of the little symmetrical gloved hand. But there were other places where money might be spent.There were books and magazines piled up in the window of a stall a few paces down the street. Mrs. Sommers bought two high-priced magazines such as she had been accustomed to read in the days when she had been accustomed to other pleasant things. She carried them without wrapping. As well as she could she lifted her skirts at the crossings. Her stockings and boots and well fitting gloves had worked marvels in her bearing--had given her a feeling of assurance, a sense of belonging to the well-dressed multitude.She was very hungry. Another time she would have stilled the cravings for food until reaching her own home, where she would have brewed herself a cup of tea and taken a snack of anything that was available. But the impulse that was guiding her would not suffer her to entertain any such thought.There was a restaurant at the corner. She had never entered its doors; from the outside she hadsometimes caught glimpses of spotless damask and shining crystal, and soft-stepping waiters serving people of fashion.When she entered her appearance created no surprise, no consternation, as she had half feared it might. She seated herself at a small table alone, and an attentive waiter at once approached to take her order. She did not want a profusion; she craved a nice and tasty bite--a half dozen blue-points, a plump chop with cress, a something sweet--a creme-frappee, for instance; a glass of Rhine wine, and after all a small cup of black coffee.While waiting to be served she removed her gloves very leisurely and laid them beside her. Then she picked up a magazine and glanced through it, cutting the pages with a blunt edge of her knife. It was all very agreeable. The damask was even more spotless than it had seemed through the window, and the crystal more sparkling. There were quiet ladies and gentlemen, who did not notice her, lunching at the small tables like her own. A soft, pleasing strain of music could be heard, and a gentle breeze, was blowing through the window. She tasted a bite, and she read a word or two, and she sipped the amber wine and wiggled her toes in the silk stockings. The price of it made no difference. She counted the money out to the waiter and left an extra coin on his tray, whereupon he bowed before her as before a princess of royal blood.There was still money in her purse, and her next temptation presented itself in the shape of a matinee poster.It was a little later when she entered the theatre, the play had begun and the house seemed to her to be packed. But there were vacant seats here and there, and into one of them she was ushered, between brilliantly dressed women who had gone there to kill time and eat candy and display their gaudy attire. There were many others who were there solely for the play and acting. It is safe to say there was no one present who bore quite the attitude which Mrs. Sommers did to her surroundings. She gathered in the whole--stage and players and people in one wide impression, and absorbed it and enjoyed it. She laughed at the comedy and wept--she and the gaudy woman next to her wept over the tragedy. And they talked a little together over it. And the gaudy woman wiped her eyes and sniffled on a tiny square of filmy, perfumed lace and passed little Mrs. Sommers her box of candy.The play was over, the music ceased, the crowd filed out. It was like a dream ended. People scattered in all directions. Mrs. Sommers went to the corner and waited for the cable car.A man with keen eyes, who sat opposite to her, seemed to like the study of her small, pale face. It puzzled him to decipher what he saw there. In truth, he saw nothing-unless he were wizard enough to detect a poignant wish, a powerful longing that the cable car would never stop anywhere, but go on and on with her forever.Cousin Tribulation's Storyby Louisa May AlcottDear Merrys:--As a subject appropriate to the season, I want to tell you about a New Year's breakfast which I had when I was a little girl. What do you think it was? A slice of dry bread and an apple. This is how it happened, and it is a true story, every word.As we came down to breakfast that morning, with very shiny faces and spandy clean aprons, we found father alone in the dining-room."Happy New Year, papa! Where is mother?" we cried."A little boy came begging and said they were starving at home, so your mother went to see and--ah, here she is."As papa spoke, in came mamma, looking very cold, rather sad, and very much excited."Children, don't begin till you hear what I have to say," she cried; and we sat staring at her, with the breakfast untouched before us."Not far away from here, lies a poor woman with a little new-born baby. Six children are huddled into one bed to keep from freezing, for they have no fire. There is nothing to eat over there; and the oldest boy came here to tell me they were starving this bitter cold day. My little girls, will you give them your breakfast, as a New Year's gift?"We sat silent a minute, and looked at the nice, hot porridge, creamy milk, and good bread and butter; for we were brought up like English children, and never drank tea or coffee, or ate anything but porridge for our breakfast."I wish we'd eaten it up," thought I, for I was rather a selfish child, and very hungry."I'm so glad you come before we began," said Nan, cheerfully."May I go and help carry it to the poor, little children?" asked Beth, who had the tenderest heart that ever beat under a pinafore."I can carry the lassy pot," said little May, proudly giving the thing she loved best."And I shall take all the porridge," I burst in, heartily ashamed of my first feeling."You shall put on your things and help me, and when we come back, we'll get something to eat," said mother, beginning to pile the bread and butter into a big basket.We were soon ready, and the procession set out. First, papa, with a basket of wood on one arm and coal on the other; mamma next, with a bundle of warm things and the teapot; Nan and I carried a pail of hot porridge between us, and each a pitcher of milk; Beth brought some cold meat, May the "lassy pot," and her old hood and boots; and Betsey, the girl, brought up the rear with a bag of potatoes and some meal.Fortunately it was early, and we went along back streets, so few people saw us, and no one laughed at the funny party.What a poor, bare, miserable place it was, to be sure,--broken windows, no fire, ragged clothes, wailing baby, sick mother, and a pile of pale, hungry children cuddled under one quilt, trying to keep warm. How the big eyes stared and the blue lips smiled as we came in!"Ah, mein Gott! it is the good angels that come to us!" cried the poor woman, with tears of joy."Funny angels, in woollen hoods and red mittens," said I; and they all laughed.Then we fell to work, and in fifteen minutes, it really did seem as if fairies had been at work there. Papa made a splendid fire in the old fireplace and stopped up the broken window with hisown hat and coat. Mamma set the shivering children round the fire, and wrapped the poor woman in warm things. Betsey and the rest of us spread the table, and fed the starving little ones."Das ist gute!" "Oh, nice!" "Der angel--Kinder!" cried the poor things as they ate and smiled and basked in the warm blaze. We had never been called "angel-children" before, and we thought it very charming, especially I who had often been told I was "a regular Sancho." What fun it was! Papa, with a towel for an apron, fed the smallest child; mamma dressed the poor little new-born baby as tenderly as if it had been her own. Betsey gave the mother gruel and tea, and comforted her with assurance of better days for all. Nan, Lu, Beth, and May flew about among the seven children, talking and laughing and trying to understand their funny, broken English. It was a very happy breakfast, though we didn't get any of it; and when we came away, leaving them all so comfortable, and promising to bring clothes and food by and by, I think there were not in all the hungry little girls who gave away their breakfast, and contented themselves with a bit of bread and an apple of New Year's day.How the Camel Got His Humpby Rudyard KiplingNOW this is the next tale, and it tells how the Camel got his big hump.In the beginning of years, when the world was so new and all, and the Animals were just beginning to work for Man, there was a Camel, and he lived in the middle of a Howling Desert because he did not want to work; and besides, he was a Howler himself. So he ate sticks and thorns and tamarisks and milkweed and prickles, most 'scruciating idle; and when anybody spoke to him he said 'Humph!' Just 'Humph!' and no more.Presently the Horse came to him on Monday morning, with a saddle on his back and a bit in his mouth, and said, 'Camel, O Camel, come out and trot like the rest of us.''Humph!' said the Camel; and the Horse went away and told the Man.Presently the Dog came to him, with a stick in his mouth, and said, 'Camel, O Camel, come and fetch and carry like the rest of us.''Humph!' said the Camel; and the Dog went away and told the Man.Presently the Ox came to him, with the yoke on his neck and said, 'Camel, O Camel, come and plough like the rest of us.''Humph!' said the Camel; and the Ox went away and told the Man.At the end of the day the Man called the Horse and the Dog and the Ox together, and said, 'Three, O Three, I'm very sorry for you (with the world so new-and-all); but that Humph-thing in the Desert can't work, or he would have been here by now, so I am going to leave him alone, and you must work double-time to make up for it.'That made the Three very angry (with the world so new-and-all), and they held a palaver, and an indaba, and a punchayet, and a pow-wow on the edge of the Desert; and the Camel came chewing on milkweed most 'scruciating idle, and laughed at them. Then he said 'Humph!' and went away again.Presently there came along the Djinn in charge of All Deserts, rolling in a cloud of dust (Djinns always travel that way because it is Magic), and he stopped to palaver and pow-pow with the Three.'Djinn of All Deserts,' said the Horse, 'is it right for any one to be idle, with the world so new-and-all?''Certainly not,' said the Djinn.'Well,' said the Horse, 'there's a thing in the middle of your Howling Desert (and he's a Howler himself) with a long neck and long legs, and he hasn't done a stroke of work since Monday morning. He won't trot.''Whew!' said the Djinn, whistling, 'that's my Camel, for all the gold in Arabia! What does he say about it?''He says "Humph!"' said the Dog; 'and he won't fetch and carry.''Does he say anything else?''Only "Humph!"; and he won't plough,' said the Ox.'Very good,' said the Djinn. 'I'll humph him if you will kindly wait a minute.'The Djinn rolled himself up in his dust-cloak, and took a bearing across the desert, and found the Camel most 'scruciatingly idle, looking at his own reflection in a pool of water.'My long and bubbling friend,' said the Djinn, 'what's this I hear of your doing no work, with theworld so new-and-all?''Humph!' said the Camel.The Djinn sat down, with his chin in his hand, and began to think a Great Magic, while the Camel looked at his own reflection in the pool of water.'You've given the Three extra work ever since Monday morning, all on account of your 'scruciating idleness,' said the Djinn; and he went on thinking Magics, with his chin in his hand.'Humph!' said the Camel.'I shouldn't say that again if I were you,' said the Djinn; you might say it once too often. Bubbles, I want you to work.'And the Camel said 'Humph!' again; but no sooner had he said it than he saw his back, that he was so proud of, puffing up and puffing up into a great big lolloping humph.'Do you see that?' said the Djinn. 'That's your very own humph that you've brought upon your very own self by not working. To-day is Thursday, and you've done no work since Monday, when the work began. Now you are going to work.''How can I,' said the Camel, 'with this humph on my back?''That's made a-purpose,' said the Djinn, 'all because you missed those three days. You will be able to work now for three days without eating, because you can live on your humph; and don't you ever say I never did anything for you. Come out of the Desert and go to the Three, and behave. Humph yourself!'And the Camel humphed himself, humph and all, and went away to join the Three. And from that day to this the Camel always wears a humph (we call it 'hump' now, not to hurt his feelings); but he has never yet caught up with the three days that he missed at the beginning of the world, and he has never yet learned how to behave.Regretby Kate ChopinMAMZELLE AURLIE possessed a good strong figure, ruddy cheeks, hair that was changing from brown to gray, and a determined eye. She wore a man's hat about the farm, and an old blue army overcoat when it was cold, and sometimes top-boots.Mamzelle Aurlie had never thought of marrying. She had never been in love. At the age of twenty she had received a proposal, which she had promptly declined, and at the age of fifty she had not yet lived to regret it.So she was quite alone in the world, except for her dog Ponto, and the negroes who lived in her cabins and worked her crops, and the fowls, a few cows, a couple of mules, her gun (with which she shot chicken-hawks), and her religion.One morning Mamzelle Aurlie stood upon her gallery, contemplating, with arms akimbo, a small band of very small children who, to all intents and purposes, might have fallen from the clouds, so unexpected and bewildering was their coming, and so unwelcome. They were the children of her nearest neighbor, Odile, who was not such a near neighbor, after all.The young woman had appeared but five minutes before, accompanied by these four children. In her arms she carried little Lodie; she dragged Ti Nomme by an unwilling hand; while Marcline and Marclette followed with irresolute steps.Her face was red and disfigured from tears and excitement. She had been summoned to a neighboring parish by the dangerous illness of her mother; her husband was away in Texas -- it seemed to her a million miles away; and Valsin was waiting with the mule-cart to drive her to the station."It's no question, Mamzelle Aurlie; you jus' got to keep those youngsters fo' me tell I come back. Dieu sait, I wouldn' botha you with 'em if it was any otha way to do! Make 'em mine you, Mamzelle Aurlie; don' spare 'em. Me, there, I'm half crazy between the chil'ren, an' Lon not home, an' maybe not even to fine po' maman alive encore!" -- a harrowing possibility which drove Odile to take a final hasty and convulsive leave of her disconsolate family.She left them crowded into the narrow strip of shade on the porch of the long, low house; the white sunlight was beating in on the white old boards; some chickens were scratching in the grass at the foot of the steps, and one had boldly mounted, and was stepping heavily, solemnly, and aimlessly across the gallery. There was a pleasant odor of pinks in the air, and the sound of negroes' laughter was coming across the flowering cotton-field.Mamzelle Aurlie stood contemplating the children. She looked with a critical eye upon Marcline, who had been left staggering beneath the weight of the chubby Lodie. She surveyed with the same calculating air Marclette mingling her silent tears with the audible grief and rebellion of Ti Nomme. During those few contemplative moments she was collecting herself, determining upon a line of action which should be identical with a line of duty. She began by feeding them.If Mamzelle Aurlie's responsibilities might have begun and ended there, they could easily have been dismissed; for her larder was amply provided against an emergency of this nature. But little children are not little pigs: they require and demand attentions which were wholly unexpected by Mamzelle Aurlie, and which she was ill prepared to give.She was, indeed, very inapt in her management of Odile's children during the first few days.How could she know that Marclette always wept when spoken to in a loud and commanding tone of voice? It was a peculiarity of Marclette's. She became acquainted with Ti Nomme's passion for flowers only when he had plucked all the choicest gardenias and pinks for the apparent purpose of critically studying their botanical construction."'T ain't enough to tell 'im, Mamzelle Aurlie," Marcline instructed her; "you got to tie 'im in a chair. It's w'at maman all time do w'en he's bad: she tie 'im in a chair." The chair in which Mamzelle Aurlie tied Ti Nomme was roomy and comfortable, and he seized the opportunity to take a nap in it, the afternoon being warm.At night, when she ordered them one and all to bed as she would have shooed the chickens into the hen-house, they stayed uncomprehending before her. What about the little white nightgowns that had to be taken from the pillow-slip in which they were brought over, and shaken by some strong hand till they snapped like ox-whips? What about the tub of water which had to be brought and set in the middle of the floor, in which the little tired, dusty, sun-browned feet had every one to be washed sweet and clean? And it made Marcline and Marclette laugh merrily -- the idea that Mamzelle Aurlie should for a moment have believed that Ti Nomme could fall asleep without being told the story of Croque-mitaine or Loup-garou, or both; or that lodie could fall asleep at all without being rocked and sung to."I tell you, Aunt Ruby," Mamzelle Aurlie informed her cook in confidence; "me, I'd rather manage a dozen plantation' than fo' chil'ren. It's terrassent! Bont! don't talk to me about chil'ren!""T ain' ispected sich as you would know airy thing 'bout 'em, Mamzelle Aurlie. I see dat plainly yistiddy w'en I spy dat li'le chile playin' wid yo' baskit o' keys. You don' know dat makes chillun grow up hard-headed, to play wid keys? Des like it make 'em teeth hard to look in a lookin'-glass. Them's the things you got to know in the raisin' an' manigement o' chillun."Mamzelle Aurlie certainly did not pretend or aspire to such subtle and far-reaching knowledge on the subject as Aunt Ruby possessed, who had "raised five an' buried six" in her day. She was glad enough to learn a few little mother-tricks to serve the moment's need.Ti Nomme's sticky fingers compelled her to unearth white aprons that she had not worn for years, and she had to accustom herself to his moist kisses -- the expressions of an affectionate and exuberant nature. She got down her sewing-basket, which she seldom used, from the top shelf of the armoire, and placed it within the ready and easy reach which torn slips and buttonless waists demanded. It took her some days to become accustomed to the laughing, the crying, the chattering that echoed through the house and around it all day long. And it was not the first or the second night that she could sleep comfortably with little Lodie's hot, plump body pressed close against her, and the little one's warm breath beating her cheek like the fanning of a bird's wing.But at the end of two weeks Mamzelle Aurlie had grown quite used to these things, and she no longer complained.It was also at the end of two weeks that Mamzelle Aurlie, one evening, looking away toward the crib where the cattle were being fed, saw Valsin's blue cart turning the bend of the road. Odile sat beside the mulatto, upright and alert. As they drew near, the young woman's beaming face indicated that her home-coming was a happy one.But this coming, unannounced and unexpected, threw Mamzelle Aurlie into a flutter that was almost agitation. The children had to be gathered. Where was Ti Nomme? Yonder in the shed, putting an edge on his knife at the grindstone. And Marcline and Marclette? Cutting and fashioning doll-rags in the corner of the gallery. As for Lodie, she was safe enough in Mamzelle Aurlie's arms;。

经典英文短篇小说 (50)

My Financial Careerby Stephen LeacockWhen I go into a bank I get rattled. The clerks rattle me; the wickets rattle me; the sight of the money rattles me; everything rattles me.The moment I cross the threshold of a bank and attempt to transact business there, I become an irresponsible idiot.I knew this beforehand, but my salary had been raised to fifty dollars a month and I felt that the bank was the only place for it.So I shambled in and looked timidly round at the clerks. I had an idea that a person about to open an account must needs consult the manager.I went up to a wicket marked "Accountant." The accountant was a tall, cool devil. The very sight of him rattled me. My voice was sepulchral."Can I see the manager?" I said, and added solemnly, "alone." I don't know why I said "alone.""Certainly," said the accountant, and fetched him.The manager was a grave, calm man. I held my fifty-six dollars clutched in a crumpled ball in my pocket."Are you the manager?" I said. God knows I didn't doubt it."Yes," he said."Can I see you," I asked, "alone?" I didn't want to say "alone" again, but without it the thing seemed self-evident.The manager looked at me in some alarm. He felt that I had an awful secret to reveal."Come in here," he said, and led the way to a private room. He turned the key in the lock."We are safe from interruption here," he said; "sit down."We both sat down and looked at each other. I found no voice to speak."You are one of Pinkerton's men, I presume," he said.He had gathered from my mysterious manner that I was a detective. I knew what he was thinking, and it made me worse."No, not from Pinkerton's," I said, seeming to imply that I came from a rival agency. "To tell the truth," I went on, as if I had been prompted to lie about it, "I am not a detective at all. I have come to open an account. I intend to keep all my money in this bank."The manager looked relieved but still serious; he concluded now that I was a son of Baron Rothschild or a young Gould."A large account, I suppose," he said."Fairly large," I whispered. "I propose to deposit fifty-six dollars now and fifty dollars a month regularly."The manager got up and opened the door. He called to the accountant."Mr. Montgomery," he said unkindly loud, "this gentleman is opening an account, he will deposit fifty-six dollars. Good morning."I rose.A big iron door stood open at the side of the room."Good morning," I said, and stepped into the safe."Come out," said the manager coldly, and showed me the other way.I went up to the accountant's wicket and poked the ball of money at him with a quick convulsive movement as if I were doing a conjuring trick.My face was ghastly pale."Here," I said, "deposit it." The tone of the words seemed to mean, "Let us do this painful thing while the fit is on us."He took the money and gave it to another clerk.He made me write the sum on a slip and sign my name in a book. I no longer knew what I was doing. The bank swam before my eyes."Is it deposited?" I asked in a hollow, vibrating voice."It is," said the accountant."Then I want to draw a cheque."My idea was to draw out six dollars of it for present use. Someone gave me a chequebook through a wicket and someone else began telling me how to write it out. The people in the bank had the impression that I was an invalid millionaire. I wrote something on the cheque and thrust it in at the clerk. He looked at it."What! are you drawing it all out again?" he asked in surprise. Then I realized that I had written fifty-six instead of six. I was too far gone to reason now. I had a feeling that it was impossible to explain the thing. All the clerks had stopped writing to look at me.Reckless with misery, I made a plunge."Yes, the whole thing.""You withdraw your money from the bank?""Every cent of it.""Are you not going to deposit any more?" said the clerk, astonished."Never."An idiot hope struck me that they might think something had insulted me while I was writing the cheque and that I had changed my mind. I made a wretchedattempt to look like a man with a fearfully quick temper.The clerk prepared to pay the money."How will you have it?" he said."What?""How will you have it?""Oh"—I caught his meaning and answered without even trying to think—"in fifties."He gave me a fifty-dollar bill."And the six?" he asked dryly."In sixes," I said.He gave it me and I rushed out.As the big door swung behind me I caught the echo of a roar of laughter that went up to the ceiling of the bank. Since then I bank no more. I keep my money in cash in my trousers pocket and my savings in silver dollars in a sock.。

超短篇的英语小说作文

超短篇的英语小说作文Title: The Forgotten Letter。

In the quiet town of Willowbrook, tucked away amidst rolling hills and ancient forests, there lived an elderly widow named Mrs. Thompson. She resided in a quaint cottage at the edge of town, where the scent of wildflowers wafted through open windows in the summer and the trees whispered secrets in the winter winds.Mrs. Thompson was known for her gentle demeanor and her love for gardening. Every morning, she could be seen in her backyard, tending to her roses with meticulous care. But despite her serene appearance, Mrs. Thompson carried a weight in her heart—a secret from her past that had remained hidden for decades.One chilly afternoon, while sorting through a dusty trunk in her attic, Mrs. Thompson stumbled upon a faded envelope tucked beneath a pile of old photographs. Theenvelope bore her name in elegant script, and upon opening it, she discovered a letter addressed to her, dated many years ago.The letter was from James, her childhood sweetheart. Memories flooded back as Mrs. Thompson read the words written with such longing and affection. James had been drafted into the military during the war, and though he promised to return, the letter revealed that he had never made it back to Willowbrook.Tears welled in Mrs. Thompson's eyes as she realized the depth of her grief, buried for so long. She had never spoken of James to anyone, choosing instead to carry her sorrow silently. Now, confronted with his words once more, she felt a surge of emotions she had long suppressed.Driven by a newfound determination, Mrs. Thompson embarked on a journey through the past. She visited the places she and James had frequented—the old oak tree by the riverbank where they carved their initials, the meadow where they picnicked on lazy summer afternoons, and thesmall church where they had whispered vows of eternal love.With each step, Mrs. Thompson felt a sense of closure mingled with bittersweet nostalgia. She realized that she had spent years preserving the memory of James in her heart, cherishing their moments together like fragile treasures.One evening, as the sun dipped low over the horizon, Mrs. Thompson returned to her cottage with a sense of peace. She placed the letter from James in a frame on her mantelpiece, alongside a photograph of them as young lovers. The weight she had carried for so long seemed to lift, leaving behind a gentle warmth.In the weeks that followed, Mrs. Thompson found solacein sharing her story with those she trusted. To her surprise, she discovered that others in Willowbrook also held untold stories of love and loss. Bonds were forgedover shared experiences, weaving a tapestry of connections that spanned generations.As time passed, Mrs. Thompson continued her routine ofgardening and tending to her roses, but her heart felt lighter, as if a burden had been lifted. She knew now that the love she had once believed lost was, in fact, an enduring thread in the fabric of her life—a reminder of the beauty that could emerge from even the deepest sorrow.And so, in the quiet town of Willowbrook, where the hills whispered and the wildflowers bloomed, Mrs. Thompson learned that some stories are meant to be shared, even if they are long forgotten. And in sharing, she discovered the timeless truth that love, once cherished, can never truly be lost.。

短篇英语经典文学作品

短篇英语经典文学作品

以下是几部经典的短篇英语文学作品:

1. "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe:这是一部著名的短篇小说,讲述了一个疯狂的男子声称他能够听到自己心中的声音,最终因此被逮捕并揭示了他的罪行。

2. "The Gift of the Magi" by O. Henry:这是一个温馨的短篇小说,讲述

了一对年轻夫妇在圣诞节前夕为了给对方买礼物而卖掉了自己的珍贵物品,最终领悟到了真正的礼物的意义。

3. "The Metamorphosis" by Franz Kafka:这是一部荒诞的短篇小说,讲述了一个人变成了一只昆虫,并在家中遭到了自己家人和社会的排斥。

4. "Brave New World" by Aldous Huxley:这是一部反乌托邦的短篇小说,讲述了一个未来社会中人们被分为不同阶层,并通过药物和科技手段被控制和洗脑的故事。

5. "The Catcher in the Rye" by Salinger:虽然这不是一部短篇小说,而

是一部长篇小说,但其中的短篇小说部分也非常值得一读,例如《De Daumier-Smith's Blue Period》、《Teddy》和《Franny》等。

这些作品都是经典的短篇小说,涵盖了不同的文学风格和主题,希望您能够从中找到自己喜欢的作品。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Louisa May Alcott: A Child's Biographyby Louisa May AlcottAs much as seventy years ago, in the city of Boston, there lived a small girl who had the naughty habit of running away. On a certain April morning, almost as soon as her mother finished buttoning her dress, Louisa May Alcott slipped out of the house and up the street as fast as her feet could carry her.Louisa crept through a narrow alley and crossed several streets. It was a beautiful day, and she did not care so very much just where she went so long as she was having an adventure, all by herself. Suddenly she came upon some children who said they were going to a nice, tall ash heap to play. They asked her to join them.Louisa thought they were fine playmates, for when she grew hungry they shared some cold potatoes and bread crusts with her. She would not have thought this much of a lunch in her mother's dining-room, but for an outdoor picnic it did very well.When she tired of the ash heap she bade the children good-by, thanked them for their kindness, and hop-skipped to the Common, where she must have wandered about for hours, because, all of a sudden, it began to grow dark. Then she wanted to get home. She wanted her doll, her kitty, and her mother! It frightened her when she could not find any street that looked natural. She was hungry and tired, too. She threw herself down on some door-steps to rest and to watch the lamplighter, for you must remember this was long before there was any gas or electricity in Boston. At this moment a big dog came along. He kissed her face and hands and then sat down beside her with a sober look in his eyes, as if he were thinking: "I guess, Little Girl, you need some one to take care of you!"Poor tired Louisa leaned against his neck and was fast asleep in no time. The dog kept very still. He did not want to wake her.Pretty soon the town crier went by. He was ringing a bell and reading in a loud voice, from a paper in his hand, the description of a lost child. You see, Louisa's father and mother had missed her early in the forenoon and had looked for her in every place they could think of. Each hour they grew more worried, and at dusk they decided to hire this man to search the city.When the runaway woke up and heard what the man was shouting—"Lost—Lost—A little girl, six years old, in a pink frock, white hat, and new, green shoes"—she called out in the darkness: "Why—dat's ME!"The town crier took Louisa by the hand and led her home, where you may be sure she was welcomed with joy.Mr. and Mrs. Alcott, from first to last, had had a good many frights about thisflyaway Louisa. Once when she was only two years old they were traveling with her on a steamboat, and she darted away, in some moment when no one was noticing her, and crawled into the engine-room to watch the machinery. Of course her clothes were all grease and dirt, and she might have been caught in the machinery and hurt.You won't be surprised to know that the next day after this last affair Louisa's parents made sure that she did not leave the house. Indeed, to be entirely certain of her where-abouts, they tied her to the leg of a big sofa for a whole day!Except for this one fault, Louisa was a good child, so she felt much ashamed that she had caused her mother, whom she loved dearly, so much worry. As she sat there, tied to the sofa, she made up her mind that she would never frighten her so again. No—she would cure herself of the running-away habit!After that day, whenever she felt the least desire to slip out of the house without asking permission, she would hurry to her own little room and shut the door tight. To keep her mind from bad plans she would shut her eyes and make up stories—think them all out, herself, you know. Then, when some of them seemed pretty good, she would write them down so that she would not forget them. By and by she found she liked making stories better than anything she had ever done in her life.Her mother sometimes wondered why Louisa grew so fond of staying in her little chamber at the head of the stairs, all of a sudden, but was pleased that the runaway child had changed into such a quiet, like-to-stay-at-home girl.It was a long time before Louisa dared to mention the stories and rhymes she had hidden in her desk but finally she told her mother about them, and when Mrs. Alcott had read them, she advised her to keep on writing. Louisa did so and became one of the best American story-tellers. She wrote a number of books, and if you begin with Lulu's Library, you will want to read Little Men and Little Women and all the books that dear Louisa Alcott ever wrote.At first Louisa was paid but small sums for her writings, and as the Alcott family were poor, she taught school, did sewing, took care of children, or worked at anything, always with a merry smile, so long as it provided comforts for those she loved.When the Civil War broke out, she was anxious to do something to help, so she went into one of the Union hospitals as a nurse. She worked so hard that she grew very ill, and her father had to go after her and bring her home. One of her books tells about her life in the hospital.It was soon after her return home that her books began to sell so well that she found herself, for the first time in her life, with a great deal of money. There was enough to buy luxuries for the Alcott family—there was enough for her to travel.No doubt she got more happiness in traveling than some people, for she found boys and girls in England, France, and Germany reading the very books she herself, Louisa May Alcott, had written. Then, too, at the age of fifty, she enjoyed venturing into new places just as well as she did the morning she sallied forth to Boston Common in her new green shoes!。