通过插管型喉罩与直接喉镜行经口气管插管对血流动力学影响的比较

喉罩与气管插管对全麻患者血流动力学的影响

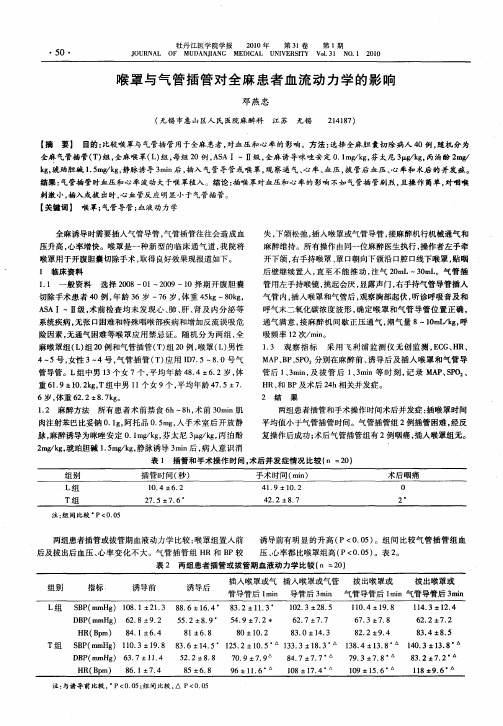

表 1 插管 和 手 术 操 作 时 间 。术 后 并 发 症情 况 比较 (n =20)

注 :组 间 比较 ‘P(0.05

两组患者插管或拔管期 血液动力 学 比较 :喉罩组 置入前 诱导前有 明显 的升高 (P<0.05)。组 间 比较 气管插 管组血 后及拔出后血 压、心率 变化不 大。气管插 管组 HR和 BP较 压 、心率都 比喉罩组高 (P<0.05)。表 2。

· 5O ·

牡丹江医学院学报 2010年 第 31卷 第 1期

JOURNAL OF MUDANJIANG MEDICAL UNIVERSITY Vo1.31 NO.1 2010

喉罩 与气 管插 管对 全 麻患 者血 流 动力 学 的影 响

邓 燕 忠

(无锡 市 惠 山 区人 民 医院麻 醉科 江 苏 无 锡 214187)

·5 1 ·

3 讨 论 喉罩置人在 胃肠 道与 呼 吸道 的交 会 处 ,具 有 良好 的通

气 ,有更易于耐受 ,具 有心血管反应小 ,置人时 不需要喉镜 暴 露 声门 ,安全 ,有效 ,易置 ,成功率 100% 。在全麻最 常见 的并 发症是气 管插管存在 气道 损伤如 :喉损伤 有声带 麻痹 ,喉头 水肿 。而喉罩不直接刺激声门和气管黏 膜 ,要 求的麻 醉深度 较 浅 ,术 中易耐受 ,苏醒 期绝 大部分 患者 较气 管插 管组安 静 无躁动 ,呼吸神 志恢复 较快 ,术毕拔 管早 ,苏 醒时 间缩 短 ,术 后患者无 咽部不适者少 ,也无肺 内感染 ,咳痰量少 ,因为喉罩 不 干扰肺部 的气 道 阻力和 纤毛活 动 ,有利 于患 者早 日恢复 。 喉罩操 作技术 ,急 救 人员 学 习较 气 管插 管容 易 ,效 果 可靠 。 应用喉罩通气在急救复苏与使用喉镜 明视下 ,与气管插 管相 比较具有操作简单 的优点 ,为抢 救赢 得时 间 ,喉罩 也可较 好 地 解 决 小 口畸 形 所 致 的 困 难 气 管 插 管 ,通 气 效 果 良好 。

比较SLIPA喉罩和气管插管麻醉对老年腹腔镜手术患者全麻诱导期血流动力学、应激激素的影响

比较SLIPA喉罩和气管插管麻醉对老年腹腔镜手术患者全麻诱导期血流动力学、应激激素的影响李鑫;张瑜【摘要】目的:比较SLIPA喉罩和气管插管麻醉对老年腹腔镜手术患者全麻诱导期血流动力学、应激激素的影响.方法:选取本院2016年6月~2017年6月期间接收并行腹腔镜手术老年患者80例作为本次研究对象,分为两个组别,对照组40例采用气管插管麻醉,研究组40例采用SLIPA喉罩麻醉,比较组间麻醉效果.结果:在麻醉后,组间除了SpO2值相比较无显著差异外(P>0.05),其余血流动力学指标、应激激素水平均存在显著差异(P<0.05).结论:在老年腹腔镜手术患者中采用SLIPA喉罩麻醉,不仅能够让其血流动力学维持在稳定状况,而且能够降低应激激素水平,安全性较高.【期刊名称】《中国医疗器械信息》【年(卷),期】2017(023)023【总页数】2页(P90-91)【关键词】SLIPA喉罩;气管插管麻醉;老年腹腔镜手术;血流动力学;应激激素【作者】李鑫;张瑜【作者单位】辽宁省人民医院麻醉科辽宁沈阳 110016;沈阳军区总医院麻醉科辽宁沈阳 110016【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R614老年患者的机体免疫力较为薄弱,对强烈刺激的适应能力较差,麻醉后容易会出现诸多应激反应[1]。

本文主要研究SLIPA喉罩和气管插管麻醉对老年腹腔镜手术患者全麻诱导期血流动力学、应激激素的影响,并将结果报道如下。

将本院2016年6月~2017年6月这一时间段收治并行腹腔镜手术的40例老年患者设为对照组,采用气管插管麻醉,并将同期接收并行腹腔镜手术的另外40例老年患者设为研究组,采用SLIPA喉罩麻醉。

在80例研究对象中,男性患者占48例,女性患者占32例,年龄52~81岁,平均年龄为(53.4±3.21)岁。

在一般临床资料比较上,组间无显著差异(P>0.05)。

所有患者在手术前30min予以0.5mg的阿托品、10mg的地西泮肌肉注射,并对其心电图、血压、指脉氧等进行密切观察,给予乳酸林格氏液。

双管型喉罩通气与气管插管在急诊手术中对血流动力学影响的比较

drc l y g so ee d t c e l n b t n T )g u . B D P H n p 2 eerc re eoe d r n n iue a e tb — i t a n oc p n or h a it a o ( T r p S P、 B 、 R a d S O r eod db fr ,u r ga d5 m n ts f r n a e r a u i o w i t i u

医 研 杂 2 8 0 第3卷 学 究 志 0 年l月 0 7 第1期 0

・ 技术 ・ 额

双 管型响 的 比较

朱 建 民 贺春 燕 姚 敏 刘松 岩

摘 要 目的 评 价 双 管 型 喉 罩 通 气 与 气 管 插 管 在 急 诊 手术 中 对 血 流 动 力 学 的影 响 。方 法 急 诊 手 术 病 人 5 6例 全 麻 下 行 插管通气 , 性病情发作前 A A 急 S I ~ Ⅱ级 , 随机 分 为 茸探 双 管 型 喉 罩 插 管 组 和 直 接 喉镜 经 口气 管 插 管组 。 记 录 两 组 患 者 于 插 管 前 即刻 、 管 中、 管 后 5 i 插 插 m n的 S P D P、 B 、 B HR和 S O p 及 一 次 置 管 成 功 率 、 管 时 间 及 插 管 后 咽 喉 疼 痛 、 音 嘶 哑 等 不 良反 应 。 插 声 结 果 两 组 一 次 置 管 成 功 率 、 管 时 问 、 后 咽 喉疼 痛 、 音 嘶 哑 的发 生 率 ,L 置 术 声 P MA组 为 9 . 3 、 1. 64 % (9 7±57 s 7 1 ;T组 为 . ) 和 .% T 10 、2 . 0 % (7 9±1. ) 和 3. 9 。 P 13 s 92 % I MA组 置 管 时 间 较 T T组 明显 缩 短 ( 0 0 ) 术 后 咽喉 疼 痛 、 音 嘶 哑 发 生 率 明 显 减 少 ( P< .5 , 声 P

对比分析喉罩麻醉、气管插管麻醉在小儿麻醉中效果

对比分析喉罩麻醉、气管插管麻醉在小儿麻醉中效果安迎迎【期刊名称】《《中国医疗器械信息》》【年(卷),期】2019(025)017【总页数】2页(P104-105)【关键词】喉罩麻醉; 气管插管小儿麻醉【作者】安迎迎【作者单位】天津市北辰医院麻醉科天津 300400【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TH789气管插管麻醉是小儿手术的主要麻醉方式,但由于小儿气道解剖结构特殊,在进行插管时极易损伤气道,可能引起患儿躁动、喉痉挛、呛咳等不良反应[1]。

与气管插管相比,喉罩麻醉操作更加简单,通过使用气囊对食管、咽喉腔进行封闭,可由咽喉通气控制气道,不仅能够减小对气道的损伤,还能够减轻对心血管系统的刺激[2]。

本文将在小儿麻醉中分别使用气管插管麻醉与喉罩麻醉,并分析麻醉效果,现报道如下。

1.资料与方法1.1 临床资料选取2015年7月~2019年5月,在本院手术治疗的74例患儿。

根据麻醉方式不同,将其分为两组。

观察组37例,男性19例,女性18例,年龄1~12岁,平均(6.46±1.19)岁,手术类型:疝气手术21例,阑尾切除术11例,骨折手术5例。

对照组37例,男性20例,女性17例,年龄2~11岁,平均(6.57±1.21)岁,手术类型:疝气手术19例,阑尾切除术12例,骨折手术6例。

1.2 方法两组患儿麻醉诱导方式相同,均使用2mg/kg丙泊酚(国药准字H20133360)+0.1mg/kg咪达唑仑(国药准字H20153019)+1μg/kg舒芬太尼(国药准字H20054256)。

对照组患儿进行气管插管麻醉,静脉注射0.6mg/kg阿曲库铵(国药准字H20171002),肌肉松弛后,根据患儿年龄选择合适的导管管径进行气管插管,维持吸入0.5%~2.0%七氟醚(国药准字H20070172),氧流量0.5~2L/min,适当使用镇痛药。

观察组患儿进行喉罩麻醉,维持吸氧4min,待意识消失后,插入喉罩,维持吸入0.5%~2.0%七氟醚,维持氧流量0.5~2.0L/min,适当使用镇痛药。

喉罩麻醉与气管插管麻醉在术中的分析比较

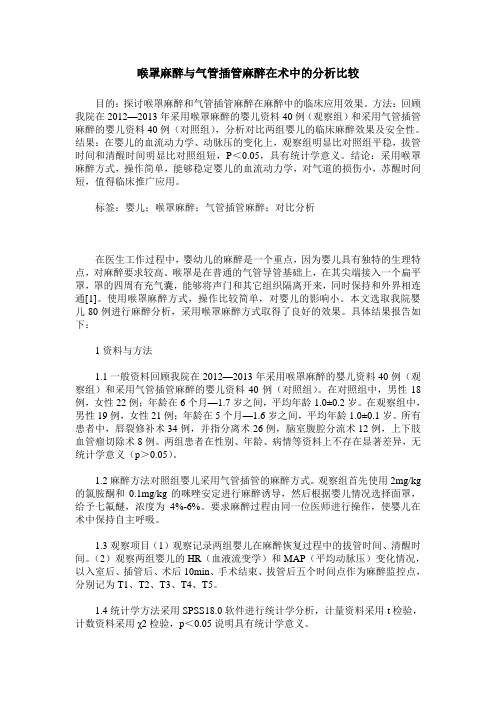

喉罩麻醉与气管插管麻醉在术中的分析比较目的:探讨喉罩麻醉和气管插管麻醉在麻醉中的临床应用效果。

方法:回顾我院在2012—2013年采用喉罩麻醉的婴儿资料40例(观察组)和采用气管插管麻醉的婴儿资料40例(对照组),分析对比两组婴儿的临床麻醉效果及安全性。

结果:在婴儿的血流动力学、动脉压的变化上,观察组明显比对照组平稳,拔管时间和清醒时间明显比对照组短,P<0.05,具有统计学意义。

结论:采用喉罩麻醉方式,操作简单,能够稳定婴儿的血流动力学,对气道的损伤小,苏醒时间短,值得临床推广应用。

标签:婴儿;喉罩麻醉;气管插管麻醉;对比分析在医生工作过程中,婴幼儿的麻醉是一个重点,因为婴儿具有独特的生理特点,对麻醉要求较高。

喉罩是在普通的气管导管基础上,在其尖端接入一个扁平罩,罩的四周有充气囊,能够将声门和其它组织隔离开来,同时保持和外界相连通[1]。

使用喉罩麻醉方式,操作比较简单,对婴儿的影响小。

本文选取我院婴儿80例进行麻醉分析,采用喉罩麻醉方式取得了良好的效果。

具体结果报告如下:1资料与方法1.1一般资料回顾我院在2012—2013年采用喉罩麻醉的婴儿资料40例(观察组)和采用气管插管麻醉的婴儿资料40例(对照组)。

在对照组中,男性18例,女性22例;年龄在6个月—1.7岁之间,平均年龄1.0±0.2岁。

在观察组中,男性19例,女性21例;年龄在5个月—1.6岁之间,平均年龄1.0±0.1岁。

所有患者中,唇裂修补术34例,并指分离术26例,脑室腹腔分流术12例,上下肢血管瘤切除术8例。

两组患者在性别、年龄、病情等资料上不存在显著差异,无统计学意义(p>0.05)。

1.2麻醉方法对照组婴儿采用气管插管的麻醉方式。

观察组首先使用2mg/kg 的氯胺酮和0.1mg/kg的咪唑安定进行麻醉诱导,然后根据婴儿情况选择面罩,给予七氟醚,浓度为4%-6%。

要求麻醉过程由同一位医师进行操作,使婴儿在术中保持自主呼吸。

《2024年三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》范文

《三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》篇一一、引言气管插管是临床麻醉和呼吸治疗中常用的技术手段,其目的在于确保患者呼吸道通畅,维持正常的气体交换。

不同的气管插管方式因其操作方法、患者舒适度及对血流动力学的影响等方面的差异,在临床应用中具有不同的适用性。

本文旨在探讨三种常见气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较。

二、材料与方法1. 材料本文研究对象为接受气管插管的患者,共计300例,其中采用第一种插管方式(如喉罩插管)的患者100例,第二种插管方式(如经典口咽插管)的患者100例,第三种插管方式(如视频喉镜引导插管)的患者100例。

2. 方法(1)对三种气管插管方式进行详细描述,包括操作步骤、适应症等;(2)通过血流动力学监测仪监测患者在插管前、插管过程中及插管后的血流动力学变化;(3)记录患者术后咽部并发症的发生情况,如咽痛、喉部水肿等;(4)对数据进行分析和比较。

三、三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响1. 喉罩插管喉罩插管在操作过程中对血流动力学的影响较小,患者在插管过程中血压、心率等指标变化较小,能够较好地维持血流动力学的稳定。

2. 经典口咽插管经典口咽插管在操作过程中对血流动力学的影响较大,患者在插管过程中可能出现血压升高、心率增快等反应,需密切关注患者生命体征变化。

3. 视频喉镜引导插管视频喉镜引导插管在操作过程中对血流动力学的影响介于喉罩插管与经典口咽插管之间,能够较好地平衡操作便利性与对患者血流动力学的影响。

四、术后咽部并发症的比较1. 咽痛三种气管插管方式术后均可能出现咽痛,其中经典口咽插管的咽痛发生率较高,可能与插管过程中对咽喉部黏膜的刺激有关。

喉罩插管和视频喉镜引导插管因操作方法不同,对咽喉部黏膜的刺激较小,咽痛发生率较低。

2. 喉部水肿喉部水肿是气管插管术后常见的并发症之一,三种气管插管方式均有发生可能。

其中,经典口咽插管的喉部水肿发生率相对较高,可能与插管过程中对喉部组织的损伤有关。

《2024年三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》范文

《三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》篇一一、引言在临床手术中,气管插管是常见且关键的医疗程序之一。

然而,由于不同插管方式对人体产生的生理效应和并发症的发生率不同,因此选择适当的插管方式对于患者的安全和康复至关重要。

本文将探讨三种常见的气管插管方式(即喉镜直视下气管插管、视频喉镜气管插管和纤维支气管镜引导下气管插管)对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较。

二、三种气管插管方式1. 喉镜直视下气管插管:此方法为传统插管方式,医生通过喉镜直视患者喉部,将气管导管插入。

2. 视频喉镜气管插管:利用高清晰度视频设备,医生可在显示屏上观察患者喉部情况,并据此插入气管导管。

3. 纤维支气管镜引导下气管插管:借助纤维支气管镜的引导,医生可将气管导管精确地插入到预定位置。

三、对血流动力学的影响1. 喉镜直视下气管插管:此方法可能导致一定的血压波动和心率变化,尤其在操作过程中刺激到气道时。

由于需要一定的技巧和经验,对于初学者来说可能存在一定的困难,容易导致血流动力学的变化。

2. 视频喉镜气管插管:由于有高清晰度视频设备的辅助,医生可以更准确地操作,减少对气道的刺激,从而降低血流动力学的变化。

3. 纤维支气管镜引导下气管插管:由于纤维支气管镜的精确引导,此方法可以更精确地将气管导管插入到预定位置,对血流动力学的影响较小。

四、术后咽部并发症的比较1. 喉镜直视下气管插管:由于操作过程中可能对咽喉部产生一定的刺激和损伤,术后咽部并发症如咽喉疼痛、声音嘶哑等较为常见。

2. 视频喉镜气管插管:由于操作更为精确,对咽喉部的刺激较小,因此术后咽部并发症的发生率相对较低。

3. 纤维支气管镜引导下气管插管:由于纤维支气管镜的精确引导,此方法可以减少对咽喉部的损伤,术后咽部并发症的发生率较低。

五、结论三种气管插管方式各有优缺点,对血流动力学和术后咽部并发症的影响也不同。

喉镜直视下气管插管虽然操作简便,但对血流动力学的影响较大,术后咽部并发症较为常见。

《2024年三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》范文

《三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》篇一一、引言在临床手术中,气管插管是一种常见的操作,其目的是为了确保患者的呼吸通畅,同时为手术提供必要的麻醉条件。

然而,不同的气管插管方式可能会对患者的血流动力学产生影响,并可能导致术后咽部并发症。

本文旨在比较三种常见的气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的差异。

二、材料与方法1. 研究对象本研究共纳入100例需要进行全身麻醉手术的患者,按照随机原则分为三组,每组采用不同的气管插管方式。

2. 气管插管方式(1)组一:采用传统喉镜气管插管法;(2)组二:采用视频喉镜气管插管法;(3)组三:采用纤维支气管镜引导的气管插管法。

3. 观察指标(1)血流动力学指标:包括心率、血压、中心静脉压等;(2)术后咽部并发症:包括咽喉疼痛、声音嘶哑、吞咽困难等。

4. 数据收集与分析在手术过程中及术后不同时间点,收集患者的血流动力学数据及咽部并发症情况,采用统计学方法进行分析。

三、三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响1. 传统喉镜气管插管法(组一)传统喉镜气管插管法在操作过程中可能会对患者的咽喉部产生一定的刺激,导致心率和血压出现一定程度的波动。

然而,经过适当的麻醉和操作技巧的调整,这种影响通常可以控制在安全范围内。

2. 视频喉镜气管插管法(组二)视频喉镜气管插管法相较于传统喉镜法具有更高的操作精度和安全性。

在操作过程中,医生可以更清晰地观察到咽喉部的结构,从而减少对周围组织的损伤。

因此,这种方法对血流动力学的影响较小,患者的心率和血压波动较小。

3. 纤维支气管镜引导的气管插管法(组三)纤维支气管镜引导的气管插管法具有较高的精确性和安全性。

由于纤维支气管镜可以直观地观察到气管内的结构,因此可以更准确地完成气管插管操作。

这种方法对血流动力学的影响也较小,患者的心率和血压波动较小。

四、三种气管插管方式术后咽部并发症的比较1. 咽喉疼痛、声音嘶哑等咽部并发症的发生率在传统喉镜组(组一)中相对较高,这可能与传统喉镜对咽喉部的刺激较大有关。

第四代喉罩与普通气管插管对血流动力学变化影响的研究

【 摘要 1 目的 进一 步观察 经第 四代 喉罩 气管插管 对血流动 力学的影 响 ; 实经 口气管插 管 时, 证

第四代 喉罩是 否能够比直接喉镜 ( L ) 生相 对轻微 的血流动力学变化。方法 DS产 择期腹 腔镜胆 囊切 除 术患者 8 0例 , 均为 A A I~Ⅱ级。随机 分为喉 罩组和 D S组 , S L 经常规静脉诱 导后气管插 管。监测麻 醉 诱 导前 ( 基础值) 后 , 、 气管插管 时和 气管插管后 5mi n内的血压 ( P 、 B ) 收缩压( B ) 舒 张压 ( B 和 心 SP 、 D P) 率( R) H 的变化 。结果 喉罩组 的平均 气管插 管操作 时间较 D S组长。气管插 管后 2组 患者 B L P和 H R

行 气 管 插 管 是 否 能 够 比 D S产 生 更 轻 微 的心 血 管 反 应 。 L

1 资 料 与 方 法

露。在 IM L A组 , 采用 Ban介绍 的标 准技 术插 入合适 型号 的 ri

IM L A和特制 的直 型硅 橡胶气 管导管。 13 观察指标 . 记录麻醉诱导前 、 醉诱导后 、 麻 插入气管 导管 时, 气管插管后 13和 5ri 、 n时的血压和心率 , a 并观察血压和心

80m 和 7 0 ~ . . m . 7 5mm的气 管导管 。所 有患 者在气 管插 k , 阿 曲 库 铵 0 1~0 5 m / g和 丙 泊 酚 1 5— g顺 . .1 g k .

管前 均 吸 氧 去 氮 3 mi, 醉 诱 导 采 用 静 脉 注 射 芬 太 尼 n麻

均 比麻 醉诱 导后 明显 升 高 , B 但 P的 最 大 值 未 超 过麻 醉 诱 导 前 水 平 , HR 的 最 大值 较 麻 醉 诱 导 前 明 显 而

《2024年三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》范文

《三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症的比较》篇一一、引言在临床手术中,气管插管是一种常见的医疗操作,用于维持患者的呼吸道通畅和进行机械通气。

不同的气管插管方式会对患者的血流动力学产生不同的影响,同时术后咽部并发症的发生率也存在差异。

本文将就三种常见的气管插管方式(经口明视插管、经鼻明视插管和经喉镜盲探插管)对血流动力学的影响及术后咽部并发症进行比较分析。

二、三种气管插管方式简介1. 经口明视插管:通过口腔直接观察声门开放情况,进行气管插管。

2. 经鼻明视插管:通过鼻腔观察声门开放情况,进行气管插管。

3. 经喉镜盲探插管:利用喉镜进行盲探式插管,不直接观察声门开放情况。

三、三种气管插管方式对血流动力学的影响1. 经口明视插管:该种插管方式在操作过程中可能会刺激口腔、咽喉等部位,导致血压升高、心率增快等血流动力学变化。

然而,由于操作者可以直接观察声门开放情况,插入过程更为精确,对血流动力学的影响相对较小。

2. 经鼻明视插管:该种插管方式对鼻腔的刺激相对较小,对血流动力学的影响也较小。

但需要注意的是,鼻腔结构与口腔不同,插管过程中可能存在一定的难度和风险。

3. 经喉镜盲探插管:该种插管方式不直接观察声门开放情况,需要依靠操作者的触感和经验进行操作。

由于插入过程较为困难,可能导致多次尝试插入,从而引起较为明显的血流动力学变化,如血压升高、心率增快等。

四、术后咽部并发症的比较1. 经口明视插管:该种插管方式术后咽部并发症主要包括口腔、咽喉部疼痛、声音改变、吞咽困难等。

由于口腔黏膜较为敏感,术后咽部并发症的发生率相对较高。

2. 经鼻明视插管:该种插管方式术后咽部并发症相对较少,主要表现在鼻腔黏膜的轻微损伤、鼻塞等症状。

由于鼻腔黏膜相对较为坚韧,术后恢复较快。

3. 经喉镜盲探插管:该种插管方式由于操作过程中可能对咽喉部造成一定的损伤,术后咽部并发症的发生率较高。

常见的并发症包括咽喉部疼痛、喉头水肿、呼吸困难等。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Original articleComparative study of hemodynamic responses to orotra- cheal intubation with intubating laryngeal mask airway and direct laryngoscopeZHANG Guo-hua, XUE Fu-shan, SUN Hai-yan, LI Cheng-wen, SUN Hai-tao, LI Ping and LIU Kun-peng Keywords: intubating laryngeal mask airway; general anesthesia; orotracheal intubation;hemodynamic responsesBackground Intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA) offers a new approach for orotracheal intubation and is expected to produce less cardiovascular stress responses. However, the available studies provide inconsistent results. The purpose of this study was to identify whether there is a clinically relevant difference in hemodynamic responses to orotracheal intubation by using ILMA and direct laryngoscope (DLS).Methods A total of 53 adult patients, ASA physical status I-II, scheduled for elective plastic surgery under general anesthesia requiring the orotracheal intubation, were randomly allocated to either DLS or ILMA groups.After a standard intravenous anesthesia induction, orotracheal intubation was performed. Noninvasive blood pressure and heart rate were recorded before (baseline values) and after anesthesia induction (post-induction values), at intubation and every minute for the first 5 minutes after intubation. The data were analyzed using Chi-square test, paired and unpaired Student's t test, and repeated-measures analysis of variance as appropriate.Results The mean intubation time in the ILMA group was longer than that in the DLS group (P<0.05). The blood pressure and heart rate increased significantly after intubation in the two groups compared to the post-induction values (P<0.05), but the maximum value of blood pressure during the observation did not exceed the baseline value, while the maximum value of heart rate was higher than the baseline (P<0.05). During the observation, there were no significant differences in blood pressure and heart rate among each time point and in the maximum values between the two groups.Conclusions Orotracheal intubations by using ILMA and DLS produce similar hemodynamic response. ILMA has no advantage in attenuating the hemodynamic responses to orotracheal intubation compared with DLS.Chin Med J 2006; 119 (11 ):899-904ntubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA) is a new device specially designed for blind orotracheal intubation.1-2 It offers several advantages over direct laryngoscope (DLS). In order to bring the glottis into the line of sight, tracheal intubation by using DLS requires distortion of surrounding oropharyn- golaryngeal structures inevitably. However, as we all know, it is impossible to distort oropharyngolaryngeal structures adequately and to exposure the glottis clearly in some cases. Anatomically curved ILMA may overcome the limitation of DLS, because it facilitates guidance of tracheal tube towards the glottis, and does not need a line of sight from the mouth to glottis. Moreover, ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation may avoid or alleviate the mechanical stimuli to the oropharyngolaryngeal structures, which are inevitable by using a rigid DLS. Theoretically, ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation leads to less severe hemodynamic responses than that by using DLS. However, some studies provide conflicting data on this issue.3-7 For example, Baskett and colleagues3 found that the tracheal intubation using ILMA produced insignificantly less hemodynamic responses, than that by using DLS. But another study showed that ILMA provided more constant blood pressure than that by DLS. Kahl etDepartment of Anesthesiology, Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100041, China (Zhang GH, Xue FS, Sun HY, Li CW, Sun HT, Li P and Liu KP)Correspondence to: Prof. XUE Fu-shan, Department of Anesthesiology, Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100041, China (Tel: 86-10-88703936. Fax: 86-10-88964137. Email: fruitxue@)Ial8 demonstrated that tracheal intubation- associated reduction of cardiovascular and endocrine stress response was more pronounced by using ILMA than that by using DLS. It is likely that these conflicting results are resulting from different duration of laryngoscopy, the times of attempts and methods of operation during ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation, and anesthetics and subject selection. In this study, we observed the hemodynamic responses to orotracheal intubation by using DLS or ILMA in adult patients under standard general anesthesia to further explore whether there is clinically relevant difference in hemodynamic response between the two intubation methods.METHODSPatientsAfter obtaining institutional ethics committee approval and written informed consent, we studied 53 adult patients, ASA physical status I-II, scheduled for elective plastic surgery under general anesthesia requiring orotracheal intubation. Of these patients, 23 were men and 30 women. Their age, weight and height ranged from 18 to 57 years, 45 to 87 kg, and 145 to 178 cm, respectively. Those who were younger than 18 or older than 60 years, taking long-term medications that may affect heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP), or having difficult airway, were excluded from this study.Study designPatients involved in this study were divided, on a random number basis (stratified by sex), into either DLS or ILMA groups. The hypothesis of this study was that there would be a clinically meaningful difference in hemodynamic responses to intubation between the groups. The number of patients for each group was determined by using an appropriate power calculation. Assuming a 1 type error of 5%, an 80% chance to detect a difference, 7 mmHg as the standard deviation in change of systolic BP (SBP), and a 50% reduction in change of SBP as being clinically significant (15 mmHg) to detect a difference between the two intubation methods, 16 patients in each group are required at least. For more reliable statistical results, a larger sample size (25 patients in each group) was used in this study. Random assignment of 25 successfully intubated patients to each group was achieved as follows: 50 index cards were placed in a box;25 cards were labeled for each group. Before each patient entered the operating room, a card was selected randomly and the patient was assigned to the indicated group. If the intubation was accomplished, the patients were included in this study, and the card was destroyed. If the intubation failed, the patient was excluded from the trial and his/her card was returned to the box.Anesthesia and intubation procedureAll the patients were fasted overnight and kept normothermic. Midazolam 0.1 mg/kg (maximum 5 mg) and scopolamine 0.01 mg/kg (maximum 0.3 mg) were given intramuscularly one hour before anesthesia. After entering the operating room, the patients was intubated with an intravenous cannula, and their BP, HR, and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) were monitored invasively with a multifunction monitor continuously (Datex-Ohmeda F-CU8, Datex Instrumentarium, Finland). Baseline values of BP and HR were recorded after a stabilization period of 5 minutes. In the DLS group, PVC Murphy-type cuffed tracheal tube (Hudson Respiratory Care Inc., USA) was used. In the ILMA group, ILMA (Laryngeal Mask Co. Ltd., UK) and specially designed straight silicone tubes (Accusil Inc., USA) were used. Tracheal tubes with internal diameter of 7.5 mm and 7.0 mm were used for male and female patients, respectively.After preoxygenation of 5 minutes, anesthesia was induced with fentanyl (2 µg/kg), vecuronium (0.1 mg/kg), and propofol (2 mg/kg) injected intrave- nously. The orotracheal intubation was started 2 minutes after vecuronium injection. All the intubations were performed by a single experienced anesthetist. In the DLS group, the tracheal tube was inserted into the trachea under a Macintosh laryngoscope according to the conventional methods, and the optimal external laryngeal manipulation was used to improve the laryngoscopic view if necessary. In the ILMA group, ILMA with suitable size was inserted using the technique described previously1 that consists of one-handed rotational movement in the sagittal plane with the head supported by a pillow to achieve a neutral position. Then, the cuff was inflated with air to reach an intracuff pressure of 60 cmH2O, and the position of the ILMA was examinedwith bag ventilation. When the ventilation was confirmed, a specially designed straight silicone tube was inserted into the ILMA immediately, and the intubation was attempted by gently advancing the tube beyond the epiglottic elevator bar. If resistance was felt, a predetermined sequence of adjusting maneuvers was performed as that recommended previously.1,2 If no resistance was felt after the tube was advanced 7 cm beyond the epiglottic elevator bar, the tube cuff was inflated and the circuit was connected to confirm correct ventilation through the tube with bag ventilation and capnography. When successful tracheal intubation was confirmed, the ILMA was removed under the help of a stabilizing rod.After the successful intubation, the tracheal tube was connected to the anesthesia breathing system for intermittent positive-pressure ventilation. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane and 60% nitrous oxide in oxygen. During the observation, a fresh gas flow of 1.5 L/min was used, and the ventilator settings were adjusted to maintain an end-expired carbon dioxide level of 35-40 mmHg and the isoflurane vaporizer was adjusted to maintain the end-tidal isoflurane concentration at 1%. Inspired concentrations of oxygen, nitrous oxide and isoflurane, and end-tidal concentration of carbon dioxide were measured and displayed digitally with a multifunction monitor (Datex-Ohmeda F-CU8). Lactated Ringer's solution was infused at a constant rate of 15 ml·kg-1·h-1 throughout the observation.Measuring variablesBP and HR were recorded after anesthetic induction (post-induction values), at intubation and every minute for the first 5 minutes after intubation. The maximum values of BP and HR during the observation were also noted. The intubation time, namely the period from termination of manual ventilation using a facemask to restarting of ventilation through the tracheal tube, was recorded using a stopwatch. Because the intubation time can significantly affect the hemodynamic response to tracheal intubation,9 patients requiring more than 120 seconds to achieve successful intubation were excluded from this study.Statistical analysisAll the data were analyzed by using SPSS 10.1 and a POMS statistical software (Version 5.0, Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, China). Demographic and clinical data from the two groups were compared using two tailed t test and Chi-square test as appropriate. Inter- and intra-group differences among the hemodynamic variables recorded over time were analyzed by using two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures, and paired and unpaired t tests with Bonferroni post-test analysis as appropriate. All quantitative data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.RESULTSQuality of orotracheal intubationTwenty-seven patients received ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation, which was completed at the first attempt in 24 cases, the second attempt in 3, and the third attempt in 1. In 3 patients, the intubation time was more than 120 seconds, because it was difficult to seek an optimal position of ILMA or insert the tracheal tube through ILMA. The other 25 patients received laryngoscopic orotracheal intubation, which was successfully performed at the first attempt in all of them with an intubation time less than 120 seconds.The 3 patients with intubation time longer than 120 seconds in the ILMA group were excluded, and then the general and hemodynamic data of the other 50 patients in the two groups were analyzed statistically. Except for intubation time, no significant difference was found between the two groups. (Tables 1 and 2)Table 1. Clinical data of patients in the two groups(n=25 in each group; mean±SD)DLS: direct laryngoscope; ILMA: intubating laryngeal mask airway.*P<0.05, compared with the DLS group. Hemodynamic changesAfter anesthetic induction, the patients' BP decreased significantly compared to the baseline value in the two groups (P<0.05), but HR remained stable. Both ILMA-guided and laryngoscopic orotracheal intubations resulted in a significant increase in BP compared to the post-induction value Groups M/F Age (y) Weight(kg)Height(cm)Intubationtime (s)DLS 10/1533.6±11.463.1±14.7 165.5±7.728.5±9.7 ILMA 11/1429.5±6.857.6±10.7 163.4±7.991.8±8.6*Table 2. Hemodynamic changes associated with the orotracheal intubation in the two groups(n =25 each; mean ±SD)DLS: direct laryngoscope; ILMA: intubating laryngeal mask airway; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate.*P <0.05 compared with the baseline values ;#P <0.05 compared with the post-induction values.(P <0.05) which, nonetheless, did not exceed the baseline value. In the DLS group, HR at intubation and 1 minute after intubation increased significantly compared to the post-induction value (P <0.05), but did not exceed the baseline values. While in the ILMA group, HR at 1 minute after intubation was significantly higher than the post-induction and baseline values (P <0.05). The maximal BP during the observation in both groups were not significantly different from the baseline values, but the maximal HR were significantly higher than the baseline values (P <0.05). There were no significant differences in BP and HR among each time point and in their maximum values during the observation between the two groups. No patient developed severe bradycardia (HR ≤50 beats/min) or severe hypotension (SBP ≤60 mmHg), and SpO 2 in all the patients were maintained at 100% in this study.DISCUSSION Laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation can cause significant pressor and tachycardiac responses by enhancing sympathetic activity. Although these are only transient cardiovascular stress responses, they are life threatening dangers to the patients suffering from the cardiocerebral vascular diseases. It has been proved that such hemodynamic responses are associated with instrument procedures through the airway, anesthetics, cardiovascular agents, patients' underlying diseases, and even their race.10-14 Because mechanic stimuli to oropharyngolaryngealstructures caused by a direct laryngoscope are considered as major causes of the hemodynamic responses to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation,15,16 many studies have focused on an intubation method that is able to attenuate or avoid the mechanic stimuli.ILMA is a new airway-securing device recently applied to clinical practice.1-2 Not only does it offer the same advantage in facilitating lung ventilation as that with standard LMA, but also it provides the superior function as an aid to the orotracheal intubation. ILMA can also be used for difficult intubation and airway management on emergencies to ventilate the patients timely and effectively.One of the prominent advantages of ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation is that it will not stimulate the base of the tongue, epiglottis, and the receptors in the pharyngeal muscles mechanically. Therefore, theoretically, ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation produces less adverse cardiovascular stress responses. However, our results showed thatorotracheal intubations by using ILMA and DLSunder general anesthesia lead to similar pressor andtachycardiac responses, which is consistent with the results of other studies on adults,5-7,10 suggesting that ILMA has no advantage in attenuating the hemodynamic responses to orotracheal intubation. Whereas, some studies showed different data. Baskett and colleagues 3 found that ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation produced statistically but not clinically significant less hemodynamic responses. In the study of Joo and Rose,4 mean arterial pressure was higher in the patients received laryngoscopicorotracheal intubation than that in those received ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation. Nevertheless, Baskett did not conduct a comparative study involving laryngoscopic intubation.3 Joo and Rose 4 did not apply the routine clinical practice becauseAfter intubation (min) Index Baseline Post- inductionAtintubation1 2 3 4 5Maximumvalues SBP (mmHg) DLS 115.6±10.8 90.8±14.5* 106.3±23.4#105.8±20.8*# 96.3±11.9* 92.4±10.9*89.2±8.8* 88.0±8.5* 113.0±23.6#ILMA 109.9±10.2 86.1±13.2* 103.3±13.2#100.0±13.6*# 92.6±13.1*89.9±12.0*87.1±10.4*86.3±11.1*106.7±13.3#DBP (mmHg)DLS 69.1±9.8 50.1±10.2* 67.1±17.7#59.7±10.87*#52.8±7.9* 50.0±7.8* 48.5±9.0* 48.0±9.1* 69.9±17.4#ILMA69.5±8.449.0±9.2*62.3±11.1*#57.2±11.25*#51.4±9.9* 47.8±8.5* 45.6±9.6* 46.1±8.3* 67.8±13.4#HR (bpm) DLS 79.5±9.4 78.3±10.4 85.2±12.0#84.1±10.0#83.9±10.9 82.7±10.4 81.2±10.5 79.0±11.8 92.4±8.6*#ILMA 84.8±11.9 84.1±12.8 89.3±15.0 92.3±12.5*#90.0±11.3 86.3±14.1 84.0±14.0 81.7±13.0 97.2±13.4*#orotracheal intubation was performed 5 minutes after the insertion of ILMA in their study.The results of our study may be caused by multiple factors. First, ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation, which includes three steps (insert and confirm the position of ILMA, insert and confirm the position of tracheal tube, and then remove the ILMA), is a time consuming procedure compared to the intubation using DLS. In our study, the mean intubation time in the ILMA group was approximately three times greater than that in the DLS group. The longer apnea and repeated airway manipulation may enhance the hemodynamic responses.9,17-19 Second, as compared with laryngoscopic intubation, ILMA- guided orotracheal intubation may impose a greater pressure on the oropharyngeal structures and cervical vertebrae, which even exceeds capillary perfusion pressure of the pharyngeal structures, resulting in backward shifting of the cervical vertebrae,20,21 thus producing more stimuli to the local structures. Third, in order to obtain an optimal position of ILMA to facilitate the insertion of tracheal tube, it is often required to move the ILMA back and forth, grasp and lift the jaw, adjust the patient's head-neck position, and increase the volume of ILMA cuff inflation or change the size of ILMA. These auxiliary maneuvers may cause additional stimuli to the oropharyngeal structures. Previous study found that grasping and lifting the jaw upwards can cause hemodynamic responses similar to those observedin conventional laryngoscopic intubation.22 Fourth, before inserting tracheal tube into the trachea via ILMA, epiglottic elevating bar of the ILMA is lifted to elevate the epiglottis and approach the glottis, that results in stimuli to the epiglottis and periepiglottic structures. Previous work suggested that mechanical stimulus to the supralaryngeal area rich in nociceptive receptors can cause strong hemodynamic responses.23 Fifth, ILMA-guided orotracheal intubation is actually a blind procedure, and tracheal tube is likely blocked off by the down folding epiglottis, anterior commissure, vocal cords and anterior tracheal wall. When the tracheal tube is blocked off, it is necessary to rotate the tracheal tube, move the ILMA up and down, and adjust patients' head-neck position, which may further stimulate the oropharyngolaryngeal structures. We believe that these maneuvers may bring longer time or even failure in tracheal intubation by using ILMA. Sixth, it has been shown that removal of the ILMA after successful intubation is a more severe stimulus than the insertion of the ILMA and tracheal tube, and can produce more significant hemodynamic responses because of stronger frictions.24 Finally, in order to avoid accidental extubation, anesthetists often use stabilizing rod to further advance the tracheal tube that may results in more frictions against the tracheal wall and even stimulating the carina when the tracheal tube is inserted too deeply. It was demonstrated that the tracheal stimulus is another main cause of hemodynamic responses to tracheal intubation.11,22,25Based on the statements above, orotracheal intubations using ILMA and DLS lead to similar hemodynamic responses. Considering the possible more attempts or even failure in tracheal intubation, ILMA is preferred to be used as a rescue means rather than a routine method for tracheal intubation in clinical anesthesia practice.In addition, our results also showed no significant difference in the maximum values of BP and HR between the two groups, further supporting the conclusion that orotracheal intubations using ILMA and DLS result in similar hemodynamic responses. Since the maximum value of BP was not significantly different from the baseline value, and the maximum increase of HR was less than 20% of the baseline value, general anesthesia could effectively attenuate the pressor and tachycardiac responses to orotracheal intubations by using the two methods.In conclusion, orotracheal intubations by using ILMA and DLS produce similar hemodynamic responses. ILMA has no advantage in attenuating the hemodynamic responses compared to DLS.REFERENCES1. Brain AI, Verghese C, Addy EV, Kaplia A. The intubatinglaryngeal mask, I: Development of a new device forintubation of the trachea. Br J Anaesth 1997; 79:699-703.2. Brain AI, Verghese C, Addy EV, Kaplia A, Brimacombe J.The intubating laryngeal mask, ii: A preliminary clinicalreport of a new means of intubating the trachea. Br JAnaesth 1997; 79: 704-709.3. Baskett PJ, Parr MJ, Nolan JP. The intubating laryngealmask. Results of a multicentre trial with experience of500 cases. Anaesthesia 1998; 53: 1174-1179.4. Joo HS, Rose DK. The intubating laryngeal mask airwaywith and without fiberoptic guidance. Anesth Analg 1999;88: 662-666.5. Kihara S, Yaguchi Y, Watanabe S, Brimacombe J,Taguchi N, Yamasaki Y. Haemodynamic responses tothe intubating laryngeal mask and timing of removal. EurJ Anaesth 2000; 17:744-750.6. Ihara S, Watanabe S, Taguchi N, Suga A, BrimacombeJR. Tracheal intubation with the Macintosh laryngoscope vs intubating laryngeal mask airway inadults with normal airways. Anaesth Intensive Care2000; 28:281-286.7. Choyce A, Avidan MS, Harvey A, Patel C, Timberlake C,Sarang K, et al. The cardiovascular response toinsertion of the intubating laryngeal mask airway.Anaesthesia 2002; 57:330-333.8. Kahl M, Eberhart LH, Behnke H, Sanger S, Schwarz U,Vogt S, et al. Stress response to tracheal intubation inpatients undergoing coronary artery surgery: directlaryngoscopy versus an intubating laryngeal maskairway. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2004; 18:275-280.9. Stoelting RK. Circulatory changes during directlaryngoscopy and tracheal intubation: influence ofduration of laryngoscopy with or without prior lidocaine.Anesthesiology 1977; 47: 381-383.10. Imai M, Matsumura C, Hanaoka Y, Kemmotsu O.Comparison of cardiovascular responses to airwaymanagement: fiberoptic intubation using a new adapter,laryngeal mask insertion, or conventional laryngoscopicintubation. J Clin Anesth 1995; 7:14-18.11. Takahashi SJ, Mizutani T, Miyabe M, Toyooka H.Hemodynamic responses to tracheal intubation withlaryngoscope versus lightwand intubating device (Trachlight) in adults with normal airway. Anesth Analg2002; 95: 480-484.12. Helfman SM, Gold MI, DeLisser EA, Herrington CA.Which drug prevents tachycardia and hypertensionassociated with tracheal intubation: lidocaine, fentanylor esmolol? Anesth Analg 1991; 72:482-486.13. Kirvela M, Scheinin M, Lindgren L. Haemodynamic andcatecholamine responses to induction of anaesthesiaand tracheal intubation in diabetic and non-diabeticuraemic patients. Br J Anaesth 1995; 74:60-65.14. Houghton IT, Low JM, Lau JT, OH TE. An ethniccomparison of the sympathetic response to trachealintubation. Anaesthesia 1993; 48: 965-968.15. Shribman AJ, Smith G, Achola KJ. Cardiovascular andcatecholamine responses to laryngoscopy with and without tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1987;59:295-299.16. Bucx MJ, Scheck PA, Van Geel RT, Den Ouden AH,Niesing R. Measurement of forces during laryngoscopy.Anaesthesia 1992; 47: 348-351.17. Shribman AJ, Smith G, Achola KJ. Cardiovascular andcatecholamines responses to laryngoscopy with andwithout tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1987;59:295-299.18. Shinji T, Taro M, Masayuki M, Hidenori T. Hemodynamicresponses to tracheal intubation with laryngoscope versus lightwand intubating device (Trachlight) in adultswith normal airway. Anesth Analg 2002; 95:480-484.19. Singh S, Smith JE. Cardiovascular changes after thethree stages of nasotracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth2003; 91: 667-671.20. Keller C, Brimacombe J. Pharyngeal mucosal pressures,airway sealing pressures, and fiberoptic position with theintubating versus the standard laryngeal mask airway.Anesthesiology 1999; 90:1001-1006.21. Keller C, Brimacombe J, Keller K. Pressures exertedagainst the cervical vertebrae by the standard andintubating laryngeal mask airway:a randomized, controlled, cross-over study in fresh cadavers. AnesthAnalg 1999; 89:1296-1300.22. Hirabayashi Y, Hiruta M, Kawakami T, Inoue S, FukudaH, Saitoh K, et al. Effects of lightwand (Trachlight)compared with direct laryngoscopy on circulatory responses to tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1998;81:253-255.23. Hamaya Y, Dohi S. Differences in cardiovascularresponse to airway stimulation at different sites andblockade of the responses by lidocaine. Anesthesiology2000; 93:95-103.24. Shimoda O, Yoshitake A, Abe E, Koga T. Reflexresponses to insertion of the intubating laryngeal maskairway, intubation and removal of the ILMA. AnaesthIntensive Care 2002; 30:766-770.25. Adachi YU, Takamatsu I, Watanabe K, Uchihashi Y,Higuchi H, Satoh T. Evaluation of the cardiovascularresponses to fiberoptic orotracheal intubation with television monitoring: comparison with conventional direct laryngoscopy. J Clin Anesth 2000; 12:503-508.(Received June 20, 2005)Edited by LUO Dan。