会计养老金准则外文翻译

养老保险制度中英文对照外文翻译文献

养老保险制度中英文对照外文翻译文献(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)翻译:重新引入代际均衡:波兰养老保险制度摘要:波兰于1999 年通过了新的养老金制度。

这种新的养老保险制度允许波兰,以减少退休金支出(占GDP 的百分比),而不是增加它-正如预计的经合组织其他大多数国家。

本文介绍了概念背景的新系统的设计。

新系统的长期目的是确保人口代际平衡,不论情况。

这需要稳定的国内生产总值的份额分配给整个退休一代。

传统的养老金制度的目的,相反,在稳定的份额人均国内生产总值退休人员。

在人口结构的变化观察到,在过去的一夫妻几十年,这历史性的尝试,以稳定为首占GDP 的比重为退休人员严重的财政问题和经济增长负外部性,如观察许多国家。

许多国家曾试图改革其养老金制度不同的方法来尝试解决这些不断增加的费用问题。

虽然波兰改革采用了其他地方应用技术,它的设计不同于典型的做法和教训,结果是有希望的所有经合组织国家。

本文介绍了这一理论和实际应用另一种方法,因此,新的波兰养老保险制度主要特点设计。

导言人口结构的转型与政策过于短视一起造成了严重的问题在全世界许多国家地区的养老金。

传统的要素养老金制度的设计包括对捐款的薄弱环节和利益缺乏超过该系统的成本控制。

这些因素列入养老保险制度导致爆炸的设计成本,造成了负增长的外部因素和导致失业率持续高企。

因此,养老金改革的追求现已在世界各地,特别是在欧洲的政策议程的顶部。

然而,很少有国家能够在引进根本性的改革面积到了这个时候养老金。

在这种情况下,改革的定义是至关重要的。

对于本文的目的,“改革”是指改变系统,以消除而不是仅仅在边缘玩的贡献率- 结构性效率低下和退休年龄调整为短期财政和系统的参数政治传统的养老金制度已被证明是低效率的提供与社会保障。

在同一时间试图治愈这些系统阻碍了缺乏共识什么可以取代传统的制度。

讨论这问题涉及混乱的思想背景下产生的讨论参与者,以及从这些概念作为过度使用“支付即用即付”与“资金”,即“公” 与“私”,而在同一时间,忽略了数重要的经济问题。

会计准则外文文献翻译-财务会计专业

会计准则外文文献及翻译-财务会计专业(含:英文原文及中文译文)文献出处:Buschhüter M, Striegel A. IAS 37 – Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets[M]// Kommentar Internationale Rechnungslegung IFRS. Gabler, 2011:955-974.英文原文Accounting Standard (AS) 37Contingent Liabilities and Contingent AssetsBuschhüter M, Striegel AThis International Accounting Standard was approved by the IASC Board in July 1998 and became effective for financial statements covering periods beginning on or after 1 July 1999.Introduction1. IAS 37 prescribes the accounting and disclosure for all provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets, except:(a) those resulting from financial instruments that are carried at fair value;(b) those resulting from executory contracts, except where the contract is onerous. Executory contracts are contracts under which neither party has performed any of its obligations or both parties have partially performed their obligations to an equal extent;(c) those arising in insurance enterprises from contracts with policyholders;(d) those covered by another International Accounting Standard. Provisions2. The Standard defines provisions as liabilities of uncertain timing or amount. A provision should be recognised when, and only when:(a) an enterprise has a present obligation (legal or constructive) as a result of a past event; (b) it is probable (i.e. more likely than not) that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation;(c) a reliable estimate can be made of the amount of the obligation. The Standard notes that it is only in extremely rare cases that a reliable estimate will not be possible.3. The Standard defines a constructive obligation as an obligation that derives from an enterprise's actions where:(a) by an established pattern of past practice, published policies or a sufficiently specific current statement, the enterprise has indicated to other parties that it will accept certain responsibilities; (b) as a result, the enterprise has created a valid expectation on the part of those other parties that it will discharge those responsibilities.4. In rare cases, for example in a law suit, it may not be clear whether an enterprise has a present obligation. In these cases, a past event is deemed to give rise to a present obligation if, taking account of all available evidence, it is more likely than not that a present obligation exists at thebalance sheet date. An enterprise recognises a provision for that present obligation if the other recognition criteria described above are met. If it is more likely than not that no present obligation exists, the enterprise discloses a contingent liability, unless the possibility of an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits is remote.5. The amount recognized as a provision should be the best estimate of the expenditu required to settle the present obligation at the balance sheet date, in other words, the amount that an enterprise would rationally pay to settle the obligation at the balance sheet date or to transfer it to a third party at that time.6. The Standard requires that an enterprise should, in measuring a provision: (a) take risks and uncertainties into account. However, uncertainty does not justify the creation of excessive provisions or a deliberate overstatement of liabilities;(b) discount the provisions, where the effect of the time value of money is material, using a pre-tax discount rate (or rates) that reflect(s) current market assessments of the time value of money and those risks specific to the liability that have not been reflected in the best estimate of the expenditure. Where discounting is used, the increase in the provision due to the passage of time is recognised as an interest expense;(c) take future events, such as changes in the law and technological changes, into account where there is sufficient objective evidence thatthey will occur; and(d) not take gains from the expected disposal of assets into account, even if the expected disposal is closely linked to the event giving rise to the provision.7. An enterprise may expect reimbursement of some or all of the expenditure required to settle a provision (for example, through insurance contracts, indemnity clauses or suppliers' warranties). An enterprise should:(a) recognise a reimbursement when, and only when, it is virtually certain that reimbursement will be received if the enterprise settles the obligation. The amount recognised for the reimbursement should not exceed the amount of the provision; and(b) recognise the reimbursement as a separate asset. In the income statement, the expense relating to a provision may be presented net of the amount recognised for a reimbursement. 8. Provisions should be reviewed at each balance sheet date and adjusted reflect thecurrent best estimate. If it is no longer probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation, the provisioshould be reversed.9. A provision should be used only for expenditures for which the provision was originally recognised.Provisions - Specific Applications10. The Standard explains how the general recognition and measurement requirements for provisions should be applied in three specific cases: future operating losses; onerous contracts; and restructurings. Contingent Liabilities11. An enterprise should not recognise a contingent liability. , unless the12. A contingent liability is disclosed, as required by paragraph 86possibility of an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits is remote.13. Where an enterprise is jointly and severally liable for an obligation, the part of tobligation that is expected to be met by other parties is treated as a contingentThe enterprise recognises a provision for the part of the obligation for which an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits is probable, except in the extremely rare circumstances where no reliable estimate can be made.14. Contingent liabilities may develop in a way not initially expected. Therefore, theare assessed continually to determine whether an outflow of resources embodying probable. If it becomes probable that an outflow of economic benefits has become future economic benefits will be required for an item previously dealt with as a contingent liability, a provision is recognised in the financial statements of the period in which the change in probability occurs (except in the extremely rare circumstances where no reliable estimate can be made).Contingent Assets15. An enterprise should not recognise a contingent asset.16. Contingent assets usually arise from unplanned or other unexpected events that give rise to the possibility of an inflow of economic benefits to the enterprise. An example is a claim that an enterprise is pursuing through legal processes, where the outcome is uncertain. 17. Contingent assets are not recognised in financial statements since this may result in the recognition of income that may never be realised. However, when the realisation of income is virtually certain, then the related asset is not a contingent asset and its recognition is appropriate. 18. A contingent asset is disclosed, as required by paragraph 89 economic benefits is probable.19. Contingent assets are assessed continually to ensure that developments are appropriately reflected in the financial statements. If it has become virtually certain that an inflow of economic benefits will arise, the asset and the related income are recognised in the financial statements of the period in which the change occurs. If an inflow of economic benefits has become probable, an enterprise discloses the contingent asset.Measurement20. The amount recognised as a provision should be the best estimate of the expenditure required to settle the present obligation at the balance sheet date.21. The best estimate of the expenditure required to settle the present obligation is the amount that an enterprise would rationally pay to settle the obligation at the balance sheet date or to transfer it to a third party at that time. It will often be impossible or prohibitively expensive to settle or transfer an obligation at the balance sheet date. However, the estimate of the amount that an enterprise would rationally pay to settle or transfer the obligation gives the best estimate of the expenditure required to settle the present obligation at the balance sheet date. 22. The estimates of outcome and financial effect are determined by the judgement of the management of the enterprise, supplemented by experience of similar transactions and, in some cases, reports from independent experts. The evidence considered23. Uncertainties surrounding the amount to be recognised as a provision are dealt with by various means according to the circumstances. Where the provision being measured involves a large population of items, the obligation is estimated by weighting all possible outcomes by their associated probabilities. The name for thistatistical method of estimation is 'expected value'. The provision will therefore be different depending on whether the probability of a loss of a given amount is, for example, 60 per cent or 90 per cent. Where there is a continuous range of possible outcomes, and each point in that range is as likely as any other, the mid-point of thrange is used. 24. Where a single obligation is beingmeasured, the individual most likely outcome may be the best estimate of the liability. However, even in such a case, the enterprise considers other possible outcomes. Where other possible outcomes are either mostly higher or mostly lower than the most likely outcome, the best estimate will be a higher or lower amount. For example, if an enterprise has to rectify a serious fault in a major plant that it has constructed for a customer, the individual most likely outcome may be for the repair to succeed at the first attempt at a cost of1,000, but a provision for a larger amount is made if there is a significant chance that further attempts will be necessary.25. The provision is measured before tax, as the tax consequences of the provision, , Income Taxes. and changes in it, are dealt with under IAS 12,Income Taxes.Risks and Uncertainties26. The risks and uncertainties that inevitably surround many events and the best estimate of a circumstances should be taken into account in reachin the best estmeate of a provision.27. Risk describes variability of outcome. A risk adjustment may increase the amount at which a liability is measured. Caution is needed in making judgements under conditions of uncertainty, so that income or assets are not overstated and expenses or liabilities are not understated. However, uncertainty does not justify the creation of excessive provisions or adeliberate overstatement of liabilities. For example, if the projected costs of a particularly adverse outcome are estimated on a prudent basis, that outcome is not then deliberately treated as more probable than is realistically the case. Care is needed to avoid duplicating adjustments for risk and uncertainty with consequent overstatement of a provision. Present Value28. Where the effect of the time value of money is material, the amount ofa provision should be the present value of the expenditures expected to be required to settle the obligation.29. The discount rate (or rates) should be a pre-tax rate (or rates) that reflect(s) current market assessments of the time value of money and the risks specific to the liability. The discount rate(s) should not reflect risks for which future cash flow estimates have been adjusted. Future Events 30. Future events that may affect the amount required to settle an obligation should be reflected in the amount of a provision where there is sufficient objective evidence that they will occur.31. Expected future events may be particularly important in measuring provisions. For example, an enterprise may believe that the cost of cleaning up a site at the end of its life will be reduced by future changes in technology. The amount recognised reflects a reasonable expectation of technically qualified, objective observers, taking account of all available evidence as to the technology that will be available at the time of theclean-up. Thus it is appropriate to include, for example, expected cost reductions associated with increased experience in applying existing technology or the expected cost of applying existing technology to a larger or more complex clean-up operation than has previously been carried out. However, an enterprise does not anticipate the new technology for cleaning up unless it is supported by development of a completel sufficient objective evidence.32. The effect of possible new legislation is taken into consideration in measuring an existing obligation when sufficient objective evidence exists that the legislation is virtually certain to beenacted. The variety of circumstances that arise in practice makes it impossible to specify a single event that will provide sufficient, objective evidence in every case. Evidence is required both of what legislation will demand and of whether it is virtually certain to be enacted and implemented in due course. In many cases sufficient objective evidence will not exist until the new legislation is enacted.Expected Disposal of Assets33. Gains from the expected disposal of assets should not be taken into account in measuring a provision.34. Gains on the expected disposal of assets are not taken into account in measuring a provision, even if the expected disposal is closely linked to the event giving rise to the provision. Instead, an enterprise recognisesgains on expected disposals of assets at the time specified by the International Accounting Standard dealing with the assets concerned. Reimbursements35. Where some or all of the expenditure required to settle a provision is expected to be reimbursed by another party, the reimbursement should be recognised when, and only when, it is virtually certain that reimbursement will be received if the enterprise settles the obligation. The reimbursement should be treated as a separate asset. The amount recognised for the reimbursement should not exceed the amount of the provision.36. In the income statement, the expense relating to a provision may be presented net of the amount recognised for a reimbursement.37. Sometimes, an enterprise is able to look to another party to pay part or all of the expenditure required to settle a provision (for example, through insurance contracts, indemnity clauses or suppliers' warranties). The other party may either reimburse amounts paid by the enterprise or pay the amounts directly.38. In most cases the enterprise will remain liable for the whole of the amount in question so that the enterprise would have to settle the full amount if the third party failed to pay for any reason. In this situation, a provision is recognised for the full amount of the liability, and a separate asset for the expected reimbursement is recognised when it is virtuallycertain that reimbursement will be received if the enterprise settles the liability.39. In some cases, the enterprise will not be liable for the costs in question if the third party fails to pay. In such a case the enterprise has no liability for those costs and they are not included in the provision.40. As noted in paragraph 29,severally liable is a contingent liability to the extent that it is expected that the obligation will be settled by the other parties.Changes in Provisions41. Provisions should be reviewed at each balance sheet date and adjusted to reflect the current best estimate. If it is no longer probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation, the provision should be reversed.42. Where discounting is used, the carrying amount of a provision increases in each period to reflect the passage of time. This increase is recognised as borrowing cost.Use of Provisions43. A provision should be used only for expenditures for which the provision was originally recognised.44. Only expenditures that relate to the original provision are set against it. Setting expenditures against a provision that was originally recognised for another purpose would conceal the impact of two different events.Future Operating Losses45. Provisions should not be recognised for future operating losses.46. Future operating losses do not meet the definition of a liability in paragraph 10.the general recognition criteria set out for provisions in paragraph 1447. An expectation of future operating losses is an indication that certain assets of the operation may be impaired. An enterprise tests these assets for impairment under IAS 36, Impairment of Assets.Onerous Contracts48. If an enterprise has a contract that is onerous, the present obligation under the contract should be recognised and measured as a provision. 49. Many contracts (for example, some routine purchase orders) can be cancelled without paying compensation to the other party, and therefore there is no obligation. Other contracts establish both rights and obligations for each of the contracting parties. Where events make such a contract onerous, the contract falls within the scope of this Standard and a liability exists which is recognised. Executory contracts that are not onerous fall outside the scope of this Standard. 50. This Standard defines an onerous contract as a contract in which the unavoidable costs of meeting the obligations under the contract exceed the economic benefits expected to be received under it. The unavoidable costs under a contract reflect the least net cost of exiting from the contract, which is the lower ofthe cost of fulfilling it and any compensation or penalties arising from failure to fulfil it.51. Before a separate provision for an onerous contract is established, an enterprise recognises any impairment loss that has occurred on assets dedicated to that contract(see IAS 36, Impairment of Assets). Restructuring52. The following are examples of events that may fall under the definition of restructuring: (a) sale or termination of a line of business; (b) the closure of business locations in a country or region or the relocation of business activities from one country or region to another; (c) changes in management structure, for example, eliminating a layer of management; (d) fundamental reorganisations that have a material effect on the nature and focus of the enterprise's operations.53. A provision for restructuring costs is recognised only when the general recognition are met. Paragraphs 72-83 set out how criteria for provisions set out in paragraph 14the general recognition criteria apply to restructurings.54. A constructive obligation to restructure arises only when an enterprise:(a) has a detailed formal plan for the restructuring identifying at least: (i) the business or part of a business concerned;(ii) the principal locations affected;(iii) the location, function, and approximate number of employees whowill be compensated for terminating their services;(iv) the expenditures that will be undertaken;(v) when the plan will be implemented;(b) has raised a valid expectation in those affected that it will carry out the restructuring by starting to implement that plan or announcing its main features to those affected by it. . Evidence that an enterprise has started to implement a restructuring plan would be provided, 55for example, by dismantling plant or selling assets or by the public announcement of the main features of the plan. A public announcement of a detailed plan to restructure constitutes a constructive obligation to restructure only if it is made in such a way and in sufficient detail (i.e. setting out the main features of the plan) that it gives rise to valid expectations in other parties such as customers, suppliers and employees (or their representatives) that the enterprise will carry out the restructuring.56. For a plan to be sufficient to give rise to a constructive obligation when communicated to those affected by it, its implementation needs to be planned to begin as soon as possible and to be completed in a timeframe that makes significant changes to the plan unlikely. If it is expected that there will be a long delay before the restructuring begins or that the restructuring will take an unreasonably long time, it is unlikely that the plan will raise a valid expectation on the part of others that theenterprise is at present committed to restructuring, because the timeframe allows opportunities for the enterprise to change its plans.57. A management or board decision to restructure taken before the balance sheet date does not give rise to a constructive obligation at the balance sheet date unless the enterprise has, before the balance sheet date:(a) started to implement the restructuring plan;(b) announced the main features of the restructuring plan to those affected by it in a sufficiently specific manner to raise a valid expectation in them that the enterprise will carry out the restructuring. In some cases, an enterprise starts to implement a restructuring plan, or announces its main features to those affected, only after the balance sheet date. Disclosure may be , Events After the Balance Sheet Date, if the restructuring is of required under IAS 10 such importance that its non-disclosure would affect the ability of the users of the financial statements to make proper evaluations and decisions.58. Although a constructive obligation is not created solely by a management decision, an obligation may result from other earlier events together with such a decision. For example, negotiations with employee representatives for termination payments, or with purchasers for the sale of an operation, may have been concluded subject only to board approval. Once that approval has been obtained and communicated to the other parties, the enterprise has a constructive obligation to restructure, if theconditions of paragraph 72 are met.. 59. In some countries, the ultimate authority is vested in a board whose membership gement (e.g. employees) includes representatives of interests other than those of managment.or notification to such representatives may be necessary before the board decision is taken. Because a decision by such a board involves communication to these representatives, it may result in a constructive obligation to restructure.60. No obligation arises for the sale of an operation until the enterprise is committed to the sale, i.e. there is a binding sale agreement.61. Even when an enterprise has taken a decision to sell an operation and announced that decision publicly, it cannot be committed to the sale until a purchaser has been identified and there is a binding sale agreement. Until there is a binding sale agreement, the enterprise will be able to change its mind and indeed will have to take another course of action if a purchaser cannot be found on acceptable terms. When the sale of an operation is envisaged as part of a restructuring, the assets of the operation , Impairment of Assets. When a sale is only are reviewed for impairme-ent under IAS 36part of a restructuring, a constructive obligation can arise for the other parts of the restructuring before a binding sale agreement exists.62. A restructuring provision should include only the direct expenditures arising form the restrict-uring,which are those that are both:(a) necessarily entailed by the restructuring; and(b) not associated with the ongoing activities of the enterprise.63. A restructuring provision does not include such costs as:(a) retraining or relocating continuing staff;(b) marketing; or(c) investment in new systems and distribution networks.These expenditures relate to the future conduct of the business and are not liabilities for restructuring at the balance sheet date. Such expenditures are recognised on the same basis as if they arose independently of a restructuring.64. Identifiable future operating losses up to the date of a restructuring are not included in a provision, unless they relate to an onerous contract as defined in paragraph 10. , gains on the expected disposal of assets are not taken65. As required by paragraph 51into account in measuring a restructuring provision, even if the sale of assets is envisaged as part of the restructuring.Disclosure66. For each class of provision, an enterprise should disclose:(a) the carrying amount at the beginning and end of the period;(b) additional provisions made in the period, including increases toexisting provisions; (c) amounts used (i.e. incurred and charged against the provision) during the period; (d) unused amounts reversed during the period; and(e) the increase during the period in the discounted amount arising from the passage of time and the effect of any change in the discount rate. Comparative information is not required67. An enterprise should disclose the following for each class of provision:(a) a brief description of the nature of the obligation and the expected timing of any resulting outflows of economic benefits;(b) an indication of the uncertainties about the amount or timing of those outflows. Where necessary to provide adequate information, an enterprise should disclose the major assumptions made concerning future events, as addressed in paragraph 48(c) the amount of any expected reimbursement, stating the amount of any asset that has been recognised for that expected reimbursement.68. Unless the possibility of any outflow in settlement is remote, an enterprise should disclose for each class of contingent liability at the balance sheet date a brief description of the nature of the contingent liability and, where practicable:;(a) an estimate of its financial effect, measured under paragraphs 36(b) an indication of the uncertainties relating to the amount or timing of any outflow; (c) the possibility of any reimbursement.69. In determining which provisions or contingent liabilities may be aggregated to form a class, it is necessary to consider whether the nature of the items is sufficiently similar for a single statement about them to fulfil the requirements of paragraphs 85(a)and (b) and 86(a) and (b). Thus, it may be appropriate to treat as a single class of provision amounts relating to warranties of different products, but it would not be appropriate to treat as a single class amounts relating to normal warranties and amounts that are subject to legal proceedings.70. Where a provision and a contingent liability arise from the same set of -86 in a circumstances, an enterprise makes the disclosures required by paragraphs 84 that shows the link between the provision and the contingent liability.71. Where an inflow of economic benefits is probable, an enterprise should disclose a brief description of the nature of the contingent assets at the balance sheet date, and, where practicable, an estimate of their financial effect, measured using the principles set out for provisions in paragraphs 3672. It is important that disclosures for contingent assets avoid giving misleading ndications of the likelihood of income arising.73 In extremely rare cases, disclosure of some or all of the information required by paragraphs 84-89 can be expected to prejudice seriously the position of the enterprise a dispute with other parties on the subject matterof the provision, contingent or contingent asset. In such cases, an enterprise need not disclose the information, but should disclose the general nature of the dispute, together with the fact that, and reason why, the information has not been disclosed. Transitional Provisions74. The effect of adopting this Standard on its effective date (or earlier) should be reported as an adjustment to the opening balance of retained earnings for the period in which the Standard is first adopted. Enterprises are encouraged, but not required, to adjust the opening balance of retained earnings for the earliest period presented and to restate comparative information. If comparative information is not restated, this fact should be disclosed. , Net Profit or Loss for the75. The Standard requires a different treatment from IAS 8requires Period, Fundamental Errors and Changes in Accounting Policies. IAS 8comparative information to be restated (benchmark treatment) or additional pro forma comparative information on a restated basis to be disclosed (allowed alternative reatment) unless it is impracticable to do so.。

会计养老金准则-外文翻译

外文翻译原文1The logic of pension accounting2. Pensions as an expense2.1. Early approaches to pension accountingIn the USA and UK, private-sector employer-sponsored pension arrangements began to appear in the second half of the 19th century, and were often associated with large organizations such as railways, insurance companies and banks (Hannah, 1986: 10–12; Chandar and Miranti,2007: 206). Accounting for these arrangements was often very simple. The cost recognized by the employer was effectively the cash paid in a given period. Some schemes operated on a ‗pay-as-you-go‘ basis, where the employer made no advance provision for retirement benefits. In this case, the cost each period equaled the benefits paid. In a scheme where the employer made contributions to an external fund invested in securities, out of which benefits would be paid, or made notional contributions to an internal account, the cost would be the contributions arising in each period, possibly augmented by interest on notional contributions if these were not used to purchase securities. However, many employers granted pensions to enable employees to retire, even though no advance provision had been made.The ‗expense-as-you-pay‘ accounting for pen sions was rationaliz ed through the ‗gratuity theo ry‘ of retirement benefits (McGill et al., 2004: 16).This theory proposed that retirement benefits were awarded to retirees at the discretion of the employ er, ‗as a kindly ac t on the part of an employer towards old retainers who have served him faithfully and well‘ (Pilch and Wo od, 1979: 2). Paying a pension was not necessarily an act of pure benevolence, because it could allow an employer to retire an employee who was no longer performing adequately, without incurring public criticism. The gratuity theory implied that the employer received an efficiency gain when superannuated employees retired, and that the appropriate point at which to recognize the cost of pensions was as the pensions were paid. If the employer wanted to earmark some earnings in a distinct pension reserve before employees retired, then this would be regarded as an appropriation of profit rather than as an expense. Even in structured pension schemes, the employer might include clauses denying the existence of an enforceable contract, stressing that pension benefitswere paid entirely at the employ er‘s discretion and could be discontinued at any time (Stone, 1984: 24).However, the gratuity theory rapidly came under challenge from the view that pensions constitute ‗deferred pay‘, and that employees in effect sacrifice current income in exchange for the expectation of income in the future. On this basis, early accounting theorists such as Henry Rand Hatfield suggested that employers should include in operat ing expenses ‗the amount necessary to provide for future pensions‘ (Hatfield, 1916: 194). A number of commentators observed that the calculation of such an expense was potentially highly complex, but they suggested that the calculations fell within the domain of actuaries (Stone, 1984: 26).Members of the actuarial profession had already been involved in advising on appropriate contribution rates for pension schemes involving either ex ternal or internal ‗notional‘ funding. In accounting terms, the employer would measure the annual cost of pension provision either directly in terms of amounts calculated by actuaries, if the route of internal funding was followed, or through the contributions (themselves determined by actuaries) to an external pension fund. In the case of external funding, cost would be equal to contributions due for the period, and, other than short-term accruals,pension expense would be based on cash payments (or other assets transferred) to the pension fund.2.2. The beginnings of accounting regulationEarly authoritative accounting pronouncements endorsed this essentially cash-based approach to pension cost determination. The Committee on Accounting Procedure of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued Accounting Research Bulletin No. 47 Accounting for Costs of Pension Plans in 1956, and expressed the view that ‗costs based on current and future services should be systematically accrued during the expected period of active service of the cov ered employees‘ (CAP, 1956). On closer analysis,‗systematic accrual‘ implied that employers would use the method recommended by the actuary for funding the pension plan to determine the pension expense in respect of current service. This approach was endorsed by the Accounting Principles Board (APB) in their Opinion No. 8 Accounting for the Cost of Pension Plans, issued in 1966. APB 8 is entirely cost-based – there are references to ‗balance-sheet pension accruals‘ and ‗balance-sheet pension prepayments or deferred charges‘ but no explanation of these terms or how they are to be determined. Much of the Opinion addresses not the issue of det ermining ‗normalcost‘ (‗the an nual cost assigned, under the actuarial cost method in use, to years subsequent to the inception of a pension plan or to a particular valuation dat e‘) bu t rather ‗past service cost‘ (‗pension cost assigned under the actuarial cost method in use, to years prior to the inception of a pension plan‘) and ‗prior service cost‘ (‗pens ion cost assigned, under the actuarial cost method in use, to years prior to the date of a particular actuarial valuation‘). The Opinion goes to great lengths to provide guidance on how these components of pension cost should be recognized, recommending spreading of the costs over a period up to 40 years. A number of features of the accounting treatment of pension costs need to be highlighted. First although it is not made explicit, there is an under-lying desire to arrive at a pension expense in each period that is not materially different from the em ployer‘s contributions to th e pension fund. APB 8 notes ‗the amount of the pension cost determined under this Opinion may vary from the amounfunded‘ (APB, 1966: para.43), but this situation is not analyzed in detail. For unfunded pension plans, costs are to be determined using an actuarial cost method. The criteria for the selection of an appropriate actuarial cost method are that the method is‘rational and systematic and should be consistently applied so that it results in a reasonable measure of pension cost from year to year‘.Author: Christopher J. NapierNationality: EnglishOriginate from: The CPA Journal译文一养老金会计的逻辑2养老金费用2.1早先的养老金会计在19世纪后期的美国和英国,出现了私人部门雇主赞助的养老金计划,主要集中于铁路公司和保险业、银行业等大型机构(Hannah, 1986: 10–12; Chandar and Miranti,2007: 206)。

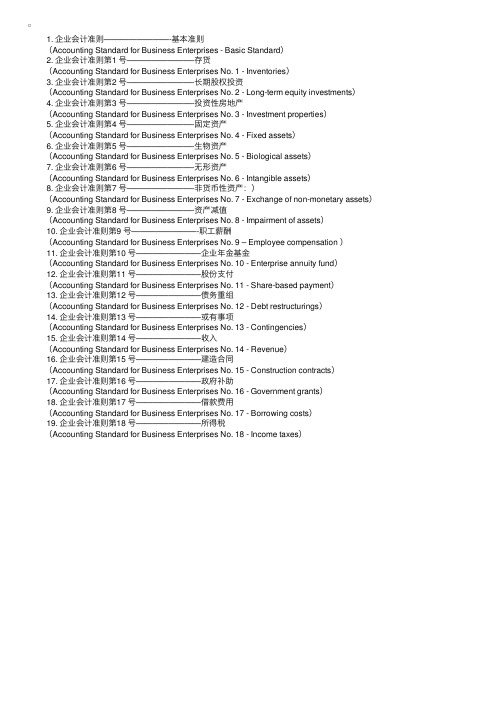

金融英语词汇辅导:会计准则中英对照

1. 企业会计准则————————-基本准则 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises - Basic Standard) 2. 企业会计准则第1 号————————-存货 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 1 - Inventories) 3. 企业会计准则第2 号————————-长期股权投资 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 2 - Long-term equity investments) 4. 企业会计准则第3 号————————-投资性房地产 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 3 - Investment properties) 5. 企业会计准则第4 号————————-固定资产 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 4 - Fixed assets) 6. 企业会计准则第5 号————————-⽣物资产 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 5 - Biological assets) 7. 企业会计准则第6 号————————-⽆形资产 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 6 - Intangible assets) 8. 企业会计准则第7 号————————-⾮货币性资产:) (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 7 - Exchange of non-monetary assets) 9. 企业会计准则第8 号————————-资产减值 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 8 - Impairment of assets) 10. 企业会计准则第9 号————————-职⼯薪酬 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 9 – Employee compensation ) 11. 企业会计准则第10 号————————企业年⾦基⾦ (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 10 - Enterprise annuity fund) 12. 企业会计准则第11 号————————股份⽀付 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 11 - Share-based payment) 13. 企业会计准则第12 号————————债务重组 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 12 - Debt restructurings) 14. 企业会计准则第13 号————————或有事项 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 13 - Contingencies) 15. 企业会计准则第14 号————————收⼊ (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 14 - Revenue) 16. 企业会计准则第15 号————————建造合同 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 15 - Construction contracts) 17. 企业会计准则第16 号————————政府补助 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 16 - Government grants) 18. 企业会计准则第17 号————————借款费⽤ (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 17 - Borrowing costs) 19. 企业会计准则第18 号————————所得税 (Accounting Standard for Business Enterprises No. 18 - Income taxes)。

外文翻译--确定有利的养老金计划,需要多少钱才够?2011-01-10

原文:Defined-benefit pension plans—How much cash is enough?By John Deinum and Winston WooRecent attention to pension issues provides a window of opportunity for policy makers to take decisive actions to implement stable, orderly and sustainable funding measures for defined-benefit pension plans.According to CFO Insights (published by Deloitte), availability of cash is one of the top concerns for every CFO. While the financial crisis may be abating, reducing costs and increasing cash flow remain top priorities in 2010. The challenge to balance strategic or operational investments against short-term management of cash is critical. For companies that offer defined-benefit (DB) plans, the challenge is magnified since potentially significant pension contributions may limit a company’s ability to make business investments that foster growth. As a result, pension benefits could be at risk because a viable DB plan requires a viable sponsor.Canada’s retirement income system ranks fourth in the world, according to the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index. The study points out that Canada’s system could be improved by increasing the level of coverage of employees in occupational pension schemes. It states: “The prevalence of private pension plans in Canada continues to decrease for employees working in the private sector.”To increase pension coverage, plans must be affordable and funding methodologies must be improved first in order to ensure stable, orderly funding.By adopting flexible and innovative funding rules, the likelihood of DB plan’s survival and expansion of coverage in the future would be improved. Otherwise, pressures to freeze DB plans or convert to a defined contribution (DC) plan will remain.The Federal government has long recognized that the regulatory framework for DB plans needs to be strengthened. Finance’s consultation paper acknowledged that:1. The combination of a significant decline in long-term interest rates, which correspond to higher pension liabilities, and poor investment returns have led tohigher pension deficits2. Excessive levels of cash flow are being directed to pension funding rather than to investment expenditures that could benefit the growth of companies and the economy more generally;3. For financially vulnerable companies, these increased cash demands could have significant implications regarding their viability;4. By funding the deficits over a short period of time, when interest rates and investment returns improve, the plan may be overfunded and it could lead to surpluses that the plan sponsors cannot utilize.In 2006, temporary measures were announced for sponsors of federally-regulated pension plans, including:1. Consolidation of all existing solvency deficiencies and reamortization over the subsequent five year period; and2. Extending the contribution schedule from five years to 10 years, with consent from members of the plan or with the use a letter of credit.The Federal government has long recognized that the regulatory framework for DB plans needs to be strengthened.The relief was only available to sponsors who filed valuation reports with The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) before 2008.In 2008, companies faced unprecedented financial turmoil that saw a near collapse of the financial system, steep declines in equity markets, recession and low interest rates. The crisisseverely hurt revenues and led to significant downsizings and business failures. In response, governments took actions to provide funding relief. In Ontario, temporary measures were announced in December 2009 that allowed companies to consolidate existing solvency payment schedules into a new five year schedule and to extend the solvency payment schedule to 10 years with plan member consent.While there is no shame in introducing temporary fixes every time a crisis arises, well-thought-out and longer-term solutions are critical to the revitalization of DB plans. The solutions must address both risks and affordability. With this in mind,below are recommendations for consideration by the stakeholders —financial executives and government policy makers. The recommendations aim to reduce the level of solvency funding contributions required with the goal that cash savings may be invested elsewhere in the business for growth and to secure future benefit accruals. While the concepts described are specific to Ontario plans, they have broader general application to federally-regulated and other provincially-regulated plans as well.A. Grow-in benefitsUnder Ontario pension legislation, a pension plan member whose age plus service is at least 55 is entitled to receive “grow-in”benefits on plan termination. For a pension plan that offers early retirement subsidies, “grow-in”provides these benefits to a member on plan termination that might not otherwise be available to the member on regular termination. Essentially with grow-in rights, the member will become entitled to an unreduced pension as if the member’s membership in the plan had continued past the date of termination. Nova Scotia and Ontario are the only two provinces that provide grow-in rights.Grow-in benefits should be eliminated from any legislative requirements.B. Pre-funding of grow-in benefitsOntario is the only province to require pre-funding of grow-in benefits as part of the solvency valuation. The cost of prefunding creates a significant cash flow burden, a cost not shared by DB plan sponsors in other provinces, putting Ontario plan sponsors at a competitive disadvantage.Nova Scotia removed the requirement to pre-fund grow-in benefits as part of a mandated solvency valuation. As a result, grow-in benefits are paid from the DB plan’s existing assets on termination. If the plan is not fully funded at termination, then the grow-in benefits are not paid.These funds may better be directed to corporate investments and ensuring the employer is viable over the long-term, thereby increasing the security of pensions accrued to date and future pensions.If grow-in benefits must be maintained under revised legislation in Ontario, theNova Scotia approach should be adopted whereby the “grow-in”benefits are not pre-funded.C. Solvency valuationSolvency valuation provides a financial position for a DB plan based on the premise that the plan is terminated on the valuation date. When solvency valuations were introduced in Ontario, virtually all pension plans had solvency liabilities substantially lower than going concern liabilities, reflecting the interest rates available to settle benefits, expected investment returns, and inflation at that time. Today, many private sector plans have solvency liabilities substantially higher than funding liabilities, reflecting the current financial climate. Pensions are by nature a long-term liability, and, as such, the funding obligations should reflect that reality. A long-term outlook enables stable plan management and reasonable contributions. The original intent of a five-year amortization period for solvency deficits is no longer realistic given current financial realities. The government needs to appreciate that DB plans represent a very long undertaking and pension benefits are long term obligations; therefore more time must be given to fund solvency deficits which are really a “best estimate”at one point in time assuming plan termination which is worst case scenario.Funding of pension deficits determined at a single point in time will be subject to significant swings caused by uncontrollable market events (such as asset returns and changes in interest rates). Allowance for such volatility should be provided by the use of longer-term average rates and amortization periods, rather than short-term market rates and the current five-year amortization period.Link the minimum funding requirements and amortization period to the level of interest rates: maintain the five-year amortization period for any solvency deficiency determined using a “normalized interest rate”or the actual solvency interest rate, if higher, and increase the amortization period to 15 years for any additional solvency deficiencies; and establish the “normalized interest rate”at 6.0 per cent per annum.D. Solvency discount rateThe Bank of Canada significantly lowered interest rates to stimulate economicrecovery and increase credit in the financial markets, resulting in a substantial decline in government bond rates which serve as the proxy for determining DB plan solvency liabilities. Lower interest rates create significantly higher pension solvency liabilities, and higher contributions for plan sponsors, offsetting benefits of the proposed relief.Use of longer-term average discount rates will stabilize plan contributions for solvency purposes and better reflect the long term nature of DB plan liabilities.Table 1 shows the lowest, average, and highest yield of long-term government bonds published by the Bank of Canada. The table was created based on the December 2009 yield on bond series V122487 (or equivalent as determined by the Bank of Canada) from 1919 to 2008. Average yields for 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 year periods ending from 1947 to 2008 were calculated.The observations range from 5.96 per cent to 6.60 per cent and suggest that use of an interest rate of six to 6.5 per cent would be appropriate.Use of a stable interest rate, based on long-term observations, to determine solvency liabilities and contributions over a five-year amortization period, combined with additional funding over a 15-year period determined as a result of market interest rates would provide significant solvency contribution relief and potentially enhance benefit security in the long term.A “normalized interest rate”of 6.0 per cent per annum should be used to establish solvency liabilities and additional liabilities, if any, determined as a result of using market interest rates be amortized over a period of 15 years.What level of benefit security should a DB plan sponsor be required to provide? The current solvency funding regulations suggest that the benefit security provided by a DB plan sponsor approach the same level as an annuity purchased from a Canadian life insurance company. This comes at a very high cost. Will significant cash flow directed to an underfunded pension plan be a contributing factor to a company’s demise, putting potential future pension benefits at risk? Would the relief proposed above allow companies to increase investments and future business prospects, ultimately providing a higher level of employment and pension security?In documents filed with courts, Nortel cited a number of times that its significantpension liabilities and contributions, expected to grow substantially due to adverse conditions in the financial markets, was one of the main reasons to seek protection under CCAA. Other high-profile publicized cases have asserted that pension funding requirements contributed to the company’s demise and sought special relief from the regulators. What is not well published are the smaller companies that simply terminated their DB plans or converted to DC in order to avoid future drain on cash flow.资料来源:CMA MANAGEME NT2010 August/September:P26-29.译文:确定有利的养老金计划,需要多少钱才够?John Deinum Winston Woo近期关注养老金问题提供了一个机会给政策制定者采取果断行动,以实施确定给付养老金计划的稳定,有序和可持续的筹资措施来确定有利的养老金计划。

最新国际会计准则ias19

目录1 概述2 目的3 范围4 定义5 退休金计划6 设立基金7 退休金计划的种类8 对退休金成本的会计处理9 揭示10 生效日期二、目的在许多国家,提供退休金成为企业对员工报酬的重要组成部分。

因此,在财务报表中对退休金费用进行适当的核算和揭示是至关重要的。

本号准则旨在阐明将提供退休金的费用确认为费用的时间以及应予确认的金额。

此外,还阐明了在企业财务报表中应于揭示的有关信息。

三、范围1.本号准则适用于对退休金计划的费用的会计处理。

2.本早准则替代于1983年发布的国际会计准则第19号“雇主财务报表中对退休金费用的会计处理”。

3.本号准则适用于根据退休金计划提取的所有退休金,无论该计划是如何制定的、正式与否,以及是否相应设立基金。

当企业依据法律或行业规划的要求,参加了国家、州、行业或其他的多重雇主退休金计划,并且参加符合退休金计划定义的雇佣终止补偿协议时,也应采用本号准则。

4.许多雇主向其雇员提供其他形式的报酬或退休福利,其中包括延期补偿安排、资深雇员的带薪假期、保健福利计划及奖金计划等。

尽管这些安排在与退休金计划本质相同时,可采用与退休金费用相似的方式进行核算和揭示,但在本号准则中将不予涉及关于这些安排的费用。

四、定义5.本号准则所使用的下列术语,具有特定的含义:退休金计划,是指企业对雇员在其终止服务时或终止服务之后,向其提供退休金的安排(或按年支付,或一次付清),该退休金或雇主为此提供的金额,应在雇员退休之前,根据有关文件的条款或企业的惯例,予以确定或预计。

规定供款的计划,是指根据供款形成的基金以及它的投资收益,来确定应支付的退休金金额的退休金计划。

规定退休金的计划,是指根据雇员的工资和服务年限,来确定应支付的退休金金额的退休金计划。

设立基金,是指为了承担未来支付退休金的义务而向企业以外的实体(基金组织)转移资产。

本期服务费用,是指企业根据退休金计划,为获得参加退休金计划的雇员在本期所提供的服务而发生的费用。

养老金会计:了解各国养老金会计准则

养老金会计:了解各国养老金会计准则引言:作为一个日益老龄化的社会,养老金成为了一个热门话题。

各国政府不得不采取措施来应对养老金问题,其中之一就是建立和实施养老金会计准则。

本文将介绍养老金会计的基本定义和目的,并深入探讨几个国家的养老金会计准则,以便更好地了解养老金会计的国际差异和趋势。

一、养老金会计的基本定义和目的1.1 养老金会计的定义养老金会计是指对企业或政府养老金计划的管理和运作进行会计核算和报告的方法和准则。

1.2 养老金会计的目的养老金会计的目的是为了提供有关养老金计划的各类信息,包括资产负债表、收入支出表等,以帮助各利益相关方做出准确的决策。

二、美国的养老金会计准则2.1 美国财务会计准则理事会(FASB)美国财务会计准则理事会(FASB)制定了《财务会计准则公开声明第87号:关于养老金会计的准则》。

该准则要求企业提供关于养老金计划的信息,包括养老金计划的具体特征、投资组合的披露、养老金资产和负债的评估等。

2.2 养老金会计的特点美国的养老金会计特点在于其披露要求的严格性和准确性。

企业必须披露养老金计划的资产和负债公允价值,并进行定期的评估和审计。

三、英国的养老金会计准则3.1 国际财务报告准则(IFRS)英国的养老金会计准则大致遵循国际财务报告准则(IFRS)。

IFRS要求企业披露养老金计划的持有资产、计划参与员工的权益以及相关的费用和收入。

3.2 英国企业会计准则委员会(ASB)英国企业会计准则委员会(ASB)为私人和非盈利机构养老金计划提供了具体的会计准则,其中包括养老金计划的定期公允价值评估和相关的披露要求。

四、中国的养老金会计准则4.1 企业会计准则中国的企业会计准则对养老金会计的相关内容有所规定,其中包括养老金计划的确认、衡量和披露等。

4.2 所得税法根据中国的所得税法,企业计提的养老金缴费可以作为税前扣除费用,这在养老金会计中需要予以考虑。

五、国际养老金会计的趋势和发展5.1 精细化的报告要求国际上养老金会计的趋势是越来越注重对养老金计划的精细化报告。

美国会计准则中文版06养老金核算reviewedbyCathyok

6-1 会计定义概述养老金计划是为职工提供福利以应对某些潜在事件,如退休、死亡、残疾、或者失业的发生。

该计划大体上可以分为“确定给付计划”及“确定缴费计划”。

两者的区别在于前者日后可以获得确定的补偿而后者平常按确定的金额缴费。

就是说,“确定给付计划”提供给参加者确定的利益,而“确定缴费计划”向每个参加者提供一个账户,并且对缴费金额和方法作了相应的规定。

确定给付计划企业对“确定给付计划”的会计核算目标有两个:(a)将养老金计划相关支出在职工服务期间计入经营费用,(b)支付养老金时同时减少相关的负债和资产。

为了减少养老金费用在财务报表中的变动幅度,企业往往将养老金支出在日后一定期间摊销,而不是一次确认为费用。

养老金费用包括年金损益、施行财务会计准则公告第87号“雇主对养老金的会计核算”的规定时预计的净资产和负债以及在养老计划实施和修改之前员工因工作而享受到的相关福利。

因此每年用于“确定给付计划”的费用包含以下几个方面:1.服务成本;2.预计给付义务的利息费用;3.该计划相关资产的实际收益;4.前期未确认服务成本的摊销;5.未确认损失及收益的摊销;6.首次采用财务会计准则公告第87号时未确认的养老金计划相关资产和负债的分摊。

由于财务会计准则公告第87号对于分期摊销的规定,很难确切对一个企业资产负债表中的预提养老金费用或待摊销养老金费用进行定义。

如果企业在采用财务会计准则公告第87号之后未修改养老金计划,并且此前所有的养老金计划相关的资产及负债均已确认,此时,报表中的预提养老金费用或待摊养老金费用则反映该计划的实际状况。

也就是说,待摊养老金费用表示相对于经营状况多付的养老金费用,而预提养老金费用则表示相对于经营状况尚未付足的养老金费用。

如果企业实行财务会计准则公告第87号,当养老金计划结算或者发生了缩减的情况,企业应记录未确认的收益和损失、前期服务费用以及由此引起的净资产或负债。

养老金计划结算以后,企业就解除了对养老金所负担的义务。

养老金外文翻译_

Protecting underfunded pensions: the role of guarantee fundsRUSSELL W. COOPERPEF, 2 (3): 247–251, 2003.f 2003 Cambridge UniversityPress247Kingdom保护资金不足的养老金:担保资金的作用罗素· W · 库珀PEF,2(3): 247–251,2003年。

f 2003 剑桥大学出版社摘要有雇主的退休金是一个补偿支付给劳动者的发达经济体,是共同的和极其重要的组成部分的公共和私营部门。

许多私人养老金资金不足,工人暴露损失的风险,因他们的用人单位停止运作,不能满足支付退休金的责任。

在本文中,我们将研究担保资金的作用,即为工人提供抵御因公司资金不足而导致福利退休金计划失败的风险。

如果实行私有化以预计养老金资金不足,我们首先考虑私人担保基金的可能性操作和探索公款一些潜在的优势。

总体而言,我们的确发现,公共资金和私人资金在提供保险方面都有一定的优势。

然而,由于需要事前溢价金资本市场不完善,以及依赖于事后捐款的资金,私人担保基金可能在战略上具有很大的不确定性。

而公共基金却可以克服这种协调性的问题。

然而,诸如美国养老金福利担保公司管理的公共基金可导致以下几个问题:(一)使本就资金不足的养老金更加缺少积累;(二)在参与市场的时候扭曲自己的决定;(三)在养老金投资组合风险过高的资产中纳入企业的决策。

在某些情况下,担保基金是不是福利的改善。

1、引言在美国,由保险养老金福利担保公司(PBGC)私人部门养老金的资金不足问题,并不和那些在20世纪80年代的储蓄和贷款机构中的危险一样。

有许多专家关注这方面问题:资金不足的计划失败暴露了保险覆盖范围并不全面以及与纳税人潜在显著的损失两个方面的问题.最近的一个由劳伦斯·怀特(1993)发起的关于通用汽车公司资金不足的讨论突出强调了一些担心,即:尽管联邦退休金福利担保公司是一家在一个基金破产是会按指定最大的数额支付养老金的公司,它有紧张的理由。

养老金会计

第6章养老金会计企业的养老金计划,从会计意义上理解,主要表现为两方面:一方面是企业对雇员承诺在未来(退休后)提供的养老金福利,或称给付义务,即为企业的养老金负债;另一方面是企业为将来偿付负债而提拨的养老基金,也就是养老金资产。

以企业为会计主体的养老金会计核算,主要是解决如何合理估计企业未来的养老金给付义务,并将此计人当期成本,以便与雇员创造的收益相配比的问题。

6.1 引言养老金(pension),通俗地讲,就是人在丧失劳动能力而被赡养时所需钱财的来源,也称退休金。

对于养老金的认识,目前主要有两种不同的观点,即“社会福利观”和“劳动报酬观”。

社会福利观认为,职工在职时所取得的工资收入已经体现了按劳分配,在退休时收取的养老金是参与剩余价值的分配,体现了国家和企业的关怀。

国家管理的养老金制度就是在这种观点的背景下产生的。

与这种观点相对应的会计处理是企业在职工退休前不需预先计提养老金,只需要在实际支付养老金时作为“营业外支出”处理。

劳动报酬观认为,养老金是劳动力价值的组成部分,是职工在职期间提供劳务所赚取的劳动报酬的一部分。

职工退休后领取的养老金是以在职时提供的劳务为依据,其实质是一项递延的报酬收入。

非国家管理的养老金制度主要是在这种观点为背景下产生。

与这种观点相对应的企业养老金会计处理是企业在职工提供劳务时就将养老金作为当期的成本费用处理。

一方面确认养老金费用,另一方面确认应计负债,以核算企业负有的向职工提存养老金的义务。

这种观点已经被世界各国会计理论界和实务界所认同。

由于养老金的来源常常要事先规划,才能保证劳动者老有所养,因此,养老金的管理需要通过“养老金计划”(pension plan)来进行。

养老金计划按照其实施主体可以分为国家的养老金计划、企业的养老金计划、个人的或者家庭的养老金计划。

譬如企业养老金计划,就是雇主因雇员在职期间提供的劳务而在雇员退休后提供(支付)给雇员的一种利益安排。

这些计划的演变以及不同计划之间的结合就形成了养老金制度。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

外文翻译原文1The logic of pension accounting2. Pensions as an expense2.1. Early approaches to pension accountingIn the USA and UK, private-sector employer-sponsored pension arrangements began to appear in the second half of the 19th century, and were often associated with large organizations such as railways, insurance companies and banks (Hannah, 1986: 10–12; Chandar and Miranti,2007: 206). Accounting for these arrangements was often very simple. The cost recognized by the employer was effectively the cash paid in a given period. Some schemes operated on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis, where the employer made no advance provision for retirement benefits. In this case, the cost each period equaled the benefits paid. In a scheme where the employer made contributions to an external fund invested in securities, out of which benefits would be paid, or made notional contributions to an internal account, the cost would be the contributions arising in each period, possibly augmented by interest on notional contributions if these were not used to purchase securities. However, many employers granted pensions to enable employees to retire, even though no advance provision had been made.The ‘expense-as-you-pay’ accounting for pen sions was rationalized through the ‘gratuity th eo ry’ of retirement benefits (McGill et al., 2004: 16).This theory proposed that retirement benefits were awarded to retirees at the discretion of the employ er, ‘as a kindly ac t on the part of an employer towards old retainers who have served him faithfully and well’ (Pilch and Wo od, 1979: 2). Paying a pension was not necessarily an act of pure benevolence, because it could allow an employer to retire an employee who was no longer performing adequately, without incurring public criticism. The gratuity theory implied that the employer received an efficiency gain when superannuated employees retired, and that the appropriate point at which to recognize the cost of pensions was as the pensions were paid. If theemployer wanted to earmark some earnings in a distinct pension reserve before employees retired, then this would be regarded as an appropriation of profit rather than as an expense. Even in structured pension schemes, the employer might include clauses denying the existence of an enforceable contract, stressing that pension benefits were paid entirely at the employ er’s discretion and could be discontinued at any time (Stone, 1984: 24).However, the gratuity theory rapidly came under challenge from the view that pensions constitute ‘deferred pay’, and that employees in effect sacrifice current income in exchange for the expectation of income in the future. On this basis, early accounting theorists such as Henry Rand Hatfield suggested that employers should include in operat ing expenses ‘the amount necessary to provide for future pensions’ (Hatfield, 1916: 194). A number of commentators observed that the calculation of such an expense was potentially highly complex, but they suggested that the calculations fell within the domain of actuaries (Stone, 1984: 26).Members of the actuarial profession had already been involved in advising on appropriate contribution rates for pension schemes involving either external or internal ‘notional’ funding. In accounting terms, the employer would measure the annual cost of pension provision either directly in terms of amounts calculated by actuaries, if the route of internal funding was followed, or through the contributions (themselves determined by actuaries) to an external pension fund. In the case of external funding, cost would be equal to contributions due for the period, and, other than short-term accruals,pension expense would be based on cash payments (or other assets transferred) to the pension fund.2.2. The beginnings of accounting regulationEarly authoritative accounting pronouncements endorsed this essentially cash-based approach to pension cost determination. The Committee on Accounting Procedure of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued Accounting Research Bulletin No. 47 Accountingfor Costs of Pension Plans in 1956, and expressed the view that ‘costs based on current and futureservices should be systematically accrued during the expected period of active service of the cov ered employees’ (CAP, 1956). On closer analysis,‘systemati c accrual’ implied that employers would use the method recommended by the actuary for funding the pension plan to determine the pension expense in respect of current service. This approach was endorsed by the Accounting Principles Board (APB) in their Opinion No. 8 Accounting for the Cost of Pension Plans, issued in 1966. APB 8 is entirely cost-based – there are references to ‘balance-sheet pension accruals’ and ‘balance-sheet pension prepayments or deferred charges’ but no explanation of these terms or how they are to be determined. Much of the Opinion addresses not the issue of det ermining ‘normal cost’ (‘the an nual cost assigned, under the actuarial cost method in use, to years subsequent to the inception of a pension plan or to a particular valuation dat e’) bu t rather ‘past service cost’ (‘pension cost assigned under the actuarial cost method in use, to years prior to the inception of a pension plan’) and ‘prior service cost’ (‘pens ion cost assigned, under the actuarial cost method in use, to years prior to the date of a particular actuarial valuation’). The Opinion goes to great lengths to provide guidance on how these components of pension cost should be recognized, recommending spreading of the costs over a period up to 40 years. A number of features of the accounting treatment of pension costs need to be highlighted. First although it is not made explicit, there is an under-lying desire to arrive at a pension expense in each period that is not materially different from the em ployer’s contributions to th e pension fund. APB 8 notes ‘the amount of the pension cost determined under this Opinion may vary from the amounfunded’(APB, 1966: para. 43), but this situation is not analyzed in detail. For unfunded pension plans, costs are to be determined using an actuarial cost method. The criteria for the selection of an appropriate actuarial cost method are that the method is‘rational and systematic and should be consistently applied so that it results in a reasonable measure of pension cost from year to year’.Author: Christopher J. NapierNationality: EnglishOriginate from: The CPA Journal译文一养老金会计的逻辑2养老金费用2.1早先的养老金会计在19世纪后期的美国和英国,出现了私人部门雇主赞助的养老金计划,主要集中于铁路公司和保险业、银行业等大型机构(Hannah, 1986: 10–12; Chandar and Miranti,2007: 206)。