荒原(中英文)—— T.S.Eliot

艾略特《荒原》

这山间甚至没有安静 只有干打的雷而没有雨 这山间甚至没有闲适 只有怒得发紫的脸嘲笑 和詈骂 从干裂的泥土房子的门 口 如果有水 而没有岩石 如果有岩石 也有水

And water A spring 350 A pool among the rock If there were the sound of water only Not the cicada And dry grass singing But sound of water over a rock 355 Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop But there is no water

那水是 一条泉 山石间的清潭 要是只有水的声音 不是知了 和枯草的歌唱 而是水流石上的清响 还有画眉鸟隐在松林里 作歌 淅沥淅沥沥沥沥 可是没有水

353 to 355 are an echo of lines 23 to 25.

“And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, And the dry stone no sound of water. Only There is shadow under this red rock” 25

WHAT THE THUNDER SAID -----------雷霆的话

AFTER the torchlight red on sweaty faces After the frosty silence in the gardens After the agony in stony places The shouting and the crying 325 Prison and place and reverberation Of thunder of spring over distant mountains He who was living is now dead We who were living are now dying With a little patience 330的面孔被火把照亮 后 在花园经过寒霜的死寂后 在岩石间的受难后 还有呐喊和哭号 监狱、宫殿和春雷 在远山的回音振荡以后 那一度活着的如今死了 我们曾活过而今却垂死 多少带一点耐心

艾略特《荒原》

弗雷泽的《金枝》是 人类历史上最伟大的 著作之一。 弗雷泽比较了多种民 族的宗教仪式,研究 了神话和仪式的基本 模式,指出远古神话 是仪式活动的产物。

《金枝》引用大量材料,说明四季循环与许多有关

神的诞生、死亡、复活的神话以及祭祀仪式有关。

渔王曾是植物神,岁末时人们哀悼他的死亡,春

天大地复苏时庆祝他的复活。

来的正是时机,他猜对了, 晚饭吃过,她厌腻而懒散, 他试着动手动脚上去温存, 虽然没受欢迎,也没有被责备。 兴奋而坚定,他立刻进攻, 探索的手没有遇到抗拒, 他的虚荣心也不需要反应, 冷漠对他等于是欢迎。 最后给了她恩赐的一吻, 探索着走出去,楼梯也没个灯亮——

她回头对镜照了一下, 全没想到还有那个离去的情人; 心里模糊地闪过一个念头: “那桩事总算完了;我很高兴。” 当美人做了失足的蠢事; 而又在屋中来回踱着,孤独地, 她机械地用手理了理头发, 并拿一张唱片放在留声机上。

后期象征主义诗人认为,自我作为纯精神的存在,

不具有被艺术直接表现的可能,只能通过与之对

应的象征来暗示。

艾略特提出寻找主观感情的“客观对应物”,把 各种情景、事件、典故等搭配成一幅幅图案来表 达某种情绪,引起共鸣。 艾略特认为诗与诗人的个人情绪没有什么关系,

提出诗歌“非个人化”的主张。

《荒原》题词

“你不知道的东西是你唯一知道的东西。”

“一首诗实际意味着什么是无关紧要的。意义不过 是扔给读者以分散注意力的肉包子;与此同时, 诗却以更加具体和更加无意识的方式悄然影响读 者”。

在艾略特看来,诗中的意义不过是个骗局,而当 人们不理解这一骗局时,自然是以某种无意识的 方式理解了诗;反之,当人们自以为把握了诗的 意义时,也就是误入圈套而不自知的时候。

在这种传统中,女性被定义为非理性,一种需要 和应当被超越的否定性 ,一个被阉割得不完整的 男人。 艾略特更是将这种思想发扬了。

荒原及汉语翻译

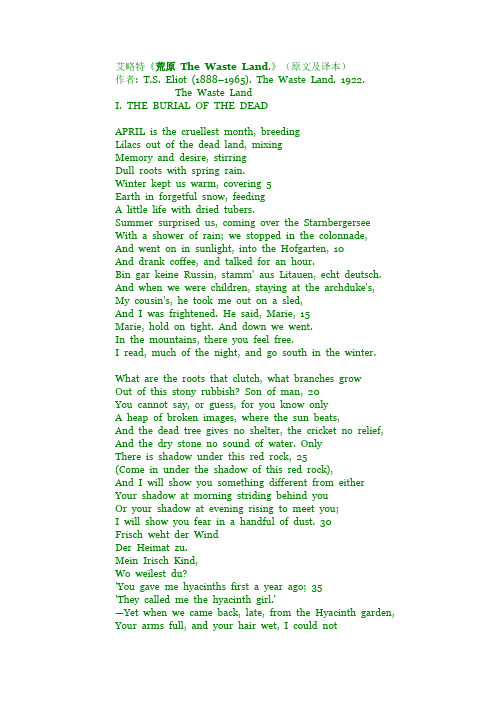

艾略特《荒原The Waste Land.》(原文及译本)作者: T.S. Eliot (1888–1965). The Waste Land. 1922.The Waste LandI. THE BURIAL OF THE DEADAPRIL is the cruellest month, breedingLilacs out of the dead land, mixingMemory and desire, stirringDull roots with spring rain.Winter kept us warm, covering 5Earth in forgetful snow, feedingA little life with dried tubers.Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, 10And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch. And when we were children, staying at the archduke's,My cousin's, he took me out on a sled,And I was frightened. He said, Marie, 15Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.In the mountains, there you feel free.I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter. What are the roots that clutch, what branches growOut of this stony rubbish? Son of man, 20You cannot say, or guess, for you know onlyA heap of broken images, where the sun beats,And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, And the dry stone no sound of water. OnlyThere is shadow under this red rock, 25(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),And I will show you something different from eitherYour shadow at morning striding behind youOr your shadow at evening rising to meet you;I will show you fear in a handful of dust. 30Frisch weht der WindDer Heimat zu.Mein Irisch Kind,Wo weilest du?'You gave me hyacinths first a year ago; 35'They called me the hyacinth girl.'—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden, Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could notSpeak, and my eyes failed, I was neitherLiving nor dead, and I knew nothing, 40Looking into the heart of light, the silence.Od' und leer das Meer.Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,Had a bad cold, neverthelessIs known to be the wisest woman in Europe, 45With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,The lady of situations. 50Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel, And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,Which is blank, is something he carries on his back, Which I am forbidden to see. I do not findThe Hanged Man. Fear death by water. 55I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:One must be so careful these days.Unreal City, 60Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,I had not thought death had undone so many.Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,And each man fixed his eyes before his feet. 65Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hoursWith a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying 'Stetson! 'You who were with me in the ships at Mylae! 70'That corpse you planted last year in your garden,'Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?'Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?'Oh keep the Dog far hence, that's friend to men,'Or with his nails he'll dig it up again! 75'You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!'II. A GAME OF CHESSTHE Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,Glowed on the marble, where the glassHeld up by standards wrought with fruited vinesFrom which a golden Cupidon peeped out 80(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra Reflecting light upon the table asThe glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,From satin cases poured in rich profusion; 85In vials of ivory and coloured glassUnstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes, Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confusedAnd drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the airThat freshened from the window, these ascended 90In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,Flung their smoke into the laquearia,Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.Huge sea-wood fed with copperBurned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone, 95 In which sad light a carvèd dolphin swam.Above the antique mantel was displayedAs though a window gave upon the sylvan sceneThe change of Philomel, by the barbarous kingSo rudely forced; yet there the nightingale 100Filled all the desert with inviolable voiceAnd still she cried, and still the world pursues,'Jug Jug' to dirty ears.And other withered stumps of timeWere told upon the walls; staring forms 105Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed. Footsteps shuffled on the stair.Under the firelight, under the brush, her hairSpread out in fiery pointsGlowed into words, then would be savagely still. 110'My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.'Speak to me. Why do you never speak? Speak.'What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?'I never know what you are thinking. Think.'I think we are in rats' alley 115Where the dead men lost their bones.'What is that noise?'The wind under the door.'What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?'Nothing again nothing. 120'Do'You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember'Nothing?'I rememberThose are pearls that were his eyes. 125'Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?'ButO O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—It's so elegantSo intelligent 130'What shall I do now? What shall I do?''I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street'With my hair down, so. What shall we do to-morrow?'What shall we ever do?'The hot water at ten. 135And if it rains, a closed car at four.And we shall play a game of chess,Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door. When Lil's husband got demobbed, I said—I didn't mince my words, I said to her myself, 140HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIMENow Albert's coming back, make yourself a bit smart.He'll want to know what you done with that money he gave yo uTo get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set, 145He said, I swear, I can't bear to look at you.And no more can't I, I said, and think of poor Albert,He's been in the army four years, he wants a good time,And if you don't give it him, there's others will, I said.Oh is there, she said. Something o' that, I said. 150Then I'll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight l ook.HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIMEIf you don't like it you can get on with it, I said.Others can pick and choose if you can't.But if Albert makes off, it won't be for lack of telling. 155You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.(And her only thirty-one.)I can't help it, she said, pulling a long face,It's them pills I took, to bring it off, she said.(She's had five already, and nearly died of young George.) 160 The chemist said it would be alright, but I've never been the sa me.You are a proper fool, I said.Well, if Albert won't leave you alone, there it is, I said,What you get married for if you don't want children?HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIME 165Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon, And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—HURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIMEHURRY UP PLEASE IT'S TIMEGoonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight. 170Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good n ight.III. THE FIRE SERMONTHE river's tent is broken: the last fingers of leafClutch and sink into the wet bank. The windCrosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed. 17 5Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song.The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette endsOr other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed. And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors; 180 Departed, have left no addresses.By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept...Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song,Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.But at my back in a cold blast I hear 185The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.A rat crept softly through the vegetationDragging its slimy belly on the bankWhile I was fishing in the dull canalOn a winter evening round behind the gashouse 190Musing upon the king my brother's wreckAnd on the king my father's death before him.White bodies naked on the low damp groundAnd bones cast in a little low dry garret,Rattled by the rat's foot only, year to year. 195But at my back from time to time I hearThe sound of horns and motors, which shall bring Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.O the moon shone bright on Mrs. PorterAnd on her daughter 200They wash their feet in soda waterEt, O ces voix d'enfants, chantant dans la coupole!Twit twit twitJug jug jug jug jug jugSo rudely forc'd. 205TereuUnreal CityUnder the brown fog of a winter noonMr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchantUnshaven, with a pocket full of currants 210C.i.f. London: documents at sight,Asked me in demotic FrenchTo luncheon at the Cannon Street HotelFollowed by a weekend at the Metropole.At the violet hour, when the eyes and back 215Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits Like a taxi throbbing waiting,I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can seeAt the violet hour, the evening hour that strives 220 Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lightsHer stove, and lays out food in tins.Out of the window perilously spreadHer drying combinations touched by the sun's last rays, 225 On the divan are piled (at night her bed)Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugsPerceived the scene, and foretold the rest—I too awaited the expected guest. 230He, the young man carbuncular, arrives,A small house agent's clerk, with one bold stare,One of the low on whom assurance sitsAs a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.The time is now propitious, as he guesses, 235The meal is ended, she is bored and tired, Endeavours to engage her in caressesWhich still are unreproved, if undesired.Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;Exploring hands encounter no defence; 240His vanity requires no response,And makes a welcome of indifference.(And I Tiresias have foresuffered allEnacted on this same divan or bed;I who have sat by Thebes below the wall 245And walked among the lowest of the dead.) Bestows on final patronising kiss,And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit...She turns and looks a moment in the glass,Hardly aware of her departed lover; 250Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass: 'Well now that's done: and I'm glad it's over.' When lovely woman stoops to folly andPaces about her room again, alone,She smoothes her hair with automatic hand, 255 And puts a record on the gramophone.'This music crept by me upon the waters'And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.O City city, I can sometimes hearBeside a public bar in Lower Thames Street, 260 The pleasant whining of a mandolineAnd a clatter and a chatter from withinWhere fishmen lounge at noon: where the wallsOf Magnus Martyr holdInexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold. 265 The river sweatsOil and tarThe barges driftWith the turning tideRed sails 270WideTo leeward, swing on the heavy spar.The barges washDrifting logsDown Greenwich reach 275Past the Isle of Dogs.Weialala leiaWallala leialalaElizabeth and LeicesterBeating oars 280The stern was formedA gilded shellRed and goldThe brisk swellRippled both shores 285Southwest windCarried down streamThe peal of bellsWhite towersWeialala leia 290Wallala leialala'Trams and dusty trees.Highbury bore me. Richmond and Kew Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe.' 295 'My feet are at Moorgate, and my heart Under my feet. After the eventHe wept. He promised "a new start".I made no comment. What should I resent?' 'On Margate Sands. 300I can connectNothing with nothing.The broken fingernails of dirty hands.My people humble people who expect Nothing.' 305la laTo Carthage then I cameBurning burning burning burningO Lord Thou pluckest me outO Lord Thou pluckest 310burningIV. DEATH BY WATERPHLEBAS the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep seas swellAnd the profit and loss.A current under sea 315Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fellHe passed the stages of his age and youthEntering the whirlpool.Gentile or JewO you who turn the wheel and look to windward, 320 Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you. V. WHAT THE THUNDER SAIDAFTER the torchlight red on sweaty facesAfter the frosty silence in the gardensAfter the agony in stony placesThe shouting and the crying 325Prison and place and reverberationOf thunder of spring over distant mountainsHe who was living is now deadWe who were living are now dyingWith a little patience 330Here is no water but only rockRock and no water and the sandy roadThe road winding above among the mountainsWhich are mountains of rock without waterIf there were water we should stop and drink 335 Amongst the rock one cannot stop or thinkSweat is dry and feet are in the sandIf there were only water amongst the rockDead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit 340There is not even silence in the mountainsBut dry sterile thunder without rainThere is not even solitude in the mountainsBut red sullen faces sneer and snarlFrom doors of mudcracked housesIf there were water 345And no rockIf there were rockAnd also waterAnd waterA spring 350A pool among the rockIf there were the sound of water onlyNot the cicadaAnd dry grass singingBut sound of water over a rock 355Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine treesDrip drop drip drop drop drop dropBut there is no waterWho is the third who walks always beside you?When I count, there are only you and I together 360But when I look ahead up the white roadThere is always another one walking beside youGliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hoodedI do not know whether a man or a woman—But who is that on the other side of you? 365What is that sound high in the airMurmur of maternal lamentationWho are those hooded hordes swarmingOver endless plains, stumbling in cracked earthRinged by the flat horizon only 370What is the city over the mountainsCracks and reforms and bursts in the violet airFalling towersJerusalem Athens AlexandriaVienna London 375UnrealA woman drew her long black hair out tightAnd fiddled whisper music on those stringsAnd bats with baby faces in the violet lightWhistled, and beat their wings 380And crawled head downward down a blackened wallAnd upside down in air were towersTolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hoursAnd voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells. In this decayed hole among the mountains 385In the faint moonlight, the grass is singingOver the tumbled graves, about the chapelThere is the empty chapel, only the wind's home.It has no windows, and the door swings,Dry bones can harm no one. 390Only a cock stood on the rooftreeCo co rico co co ricoIn a flash of lightning. Then a damp gustBringing rainGanga was sunken, and the limp leaves 395Waited for rain, while the black cloudsGathered far distant, over Himavant.The jungle crouched, humped in silence.Then spoke the thunderD A 400Datta: what have we given?My friend, blood shaking my heartThe awful daring of a moment's surrenderWhich an age of prudence can never retractBy this, and this only, we have existed 405Which is not to be found in our obituariesOr in memories draped by the beneficent spiderOr under seals broken by the lean solicitorIn our empty roomsD A 410Dayadhvam: I have heard the keyTurn in the door once and turn once onlyWe think of the key, each in his prisonThinking of the key, each confirms a prisonOnly at nightfall, aetherial rumours 415Revive for a moment a broken CoriolanusD ADamyata: The boat respondedGaily, to the hand expert with sail and oarThe sea was calm, your heart would have responded 420 Gaily, when invited, beating obedientTo controlling handsI sat upon the shoreFishing, with the arid plain behind meShall I at least set my lands in order? 425London Bridge is falling down falling down falling downPoi s'ascose nel foco che gli affinaQuando fiam ceu chelidon—O swallow swallowLe Prince d'Aquitaine àla tour abolieThese fragments I have shored against my ruins 430Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo's mad againe.Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.Shantih shantih shantih-------------------------NOTESNot only the title, but the plan and a good deal of the incident alsymbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L. Westo n'sbook on the Grail legend: From Ritual to Romance (Macmillan). Indeed, so deeply am I indebted, Miss Weston's book will eluci datethe difficulties of the poem much better than my notes can do; and Irecommend it (apart from the great interest of the book itself) toany who think such elucidation of the poem worth the trouble. Toanother work of anthropology I am indebted in general, one wh ich hasinfluenced our generation profoundly; I mean The Golden Boug h; Ihave used especially the two volumes Adonis, Attis, Osiris. Anyo newho is acquainted with these works will immediately recognize i n thepoem certain references to vegetation ceremonies.I. THE BURIAL OF THE DEADLine 20 Cf. Ezekiel 2:7.23. Cf. Ecclesiastes 12:5.31. V. Tristan und Isolde, i, verses 5–8.42. Id. iii, verse 24.46. I am not familiar with the exact constitution of the Tarot p ackof cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my own convenience. The Hanged Man, a member of the traditional pac k, fitsmy purpose in two ways: because he is associated in my mind with theHanged God of Frazer, and because I associate him with the h oodedfigure in the passage of the disciples to Emmaus in Part V. Th ePhoenician Sailor and the Merchant appear later; also the 'crow ds ofpeople', and Death by Water is executed in Part IV. The Man withThree Staves (an authentic member of the Tarot pack) I associa te,quite arbitrarily, with the Fisher King himself.60. Cf. Baudelaire:Fourmillante cité, citépleine de rêves,Oùle spectre en plein jour raccroche le passant.63. Cf. Inferno, iii. 55–7:si lunga trattadi gente, ch'io non avrei mai credutoche morte tanta n'avesse disfatta.64. Cf. Inferno, iv. 25–27:Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare,non avea pianto, ma' che di sospiri,che l'aura eterna facevan tremare.68. A phenomenon which I have often noticed.74. Cf. the Dirge in Webster's White Devil.76. V. Baudelaire, Preface to Fleurs du Mal.II. A GAME OF CHESS77. Cf. Antony and Cleopatra, II. ii. 190.92. Laquearia. V. Aeneid, I. 726:dependent lychni laquearibus aureis incensi, et noctem flammis funalia vincunt.98. Sylvan scene. V. Milton, Paradise Lost, iv. 140.99. V. Ovid, Metamorphoses, vi, Philomela.100. Cf. Part III, l. 204.115. Cf. Part III, l. 195.118. Cf. Webster: 'Is the wind in that door still?'126. Cf. Part I, l. 37, 48.138. Cf. the game of chess in Middleton's Women beware Wom en.III. THE FIRE SERMON176. V. Spenser, Prothalamion.192. Cf. The Tempest, I. ii.196. Cf. Marvell, To His Coy Mistress.197. Cf. Day, Parliament of Bees:When of the sudden, listening, you shall hear,A noise of horns and hunting, which shall bringActaeon to Diana in the spring,Where all shall see her naked skin...199. I do not know the origin of the ballad from which these li nesare taken: it was reported to me from Sydney, Australia. 202. V. Verlaine, Parsifal.210. The currants were quoted at a price 'carriage and insuranc efree to London'; and the Bill of Lading, etc., were to be handed tothe buyer upon payment of the sight draft.218. Tiresias, although a mere spectator and not indeeda 'character', is yet the most important personage in the poem, uniting all the rest. Just as the one-eyed merchant, seller of currants, melts into the Phoenician Sailor, and the latter is not wholly distinct from Ferdinand Prince of Naples, so all the wo menare one woman, and the two sexes meet in Tiresias. What Tires iassees, in fact, is the substance of the poem. The whole passage f romOvid is of great anthropological interest:...Cum Iunone iocos et 'maior vestra profecto estQuam, quae contingit maribus', dixisse, 'voluptas.'Illa negat; placuit quae sit sententia doctiQuaerere Tiresiae: venus huic erat utraque nota.Nam duo magnorum viridi coeuntia silvaCorpora serpentum baculi violaverat ictuDeque viro factus, mirabile, femina septemEgerat autumnos; octavo rursus eosdemVidit et 'est vestrae si tanta potentia plagae',Dixit 'ut auctoris sortem in contraria mutet,Nunc quoque vos feriam!' percussis anguibus isdemForma prior rediit genetivaque venit imago.Arbiter hic igitur sumptus de lite iocosaDicta Iovis firmat; gravius Saturnia iustoNec pro materia fertur doluisse suiqueIudicis aeterna damnavit lumina nocte,At pater omnipotens (neque enim licet inrita cuiquamFacta dei fecisse deo) pro lumine ademptoScire futura dedit poenamque levavit honore.221. This may not appear as exact as Sappho's lines, but I had inmind the 'longshore' or 'dory' fisherman, who returns at nightfa ll.253. V. Goldsmith, the song in The Vicar of Wakefield.257. V. The Tempest, as above.264. The interior of St. Magnus Martyr is to my mind one of t hefinest among Wren's interiors. See The Proposed Demolition of Nineteen City Churches (P. S. King & Son, Ltd.).266. The Song of the (three) Thames-daughters begins here. Fr om line292 to 306 inclusive they speak in turn. V. Götterdammerung, I II.i: The Rhine-daughters.279. V. Froude, Elizabeth, vol. I, ch. iv, letter of De Quadra to Philip of Spain:In the afternoon we were in a barge, watching the games on th eriver. (The queen) was alone with Lord Robert and myself on t hepoop, when they began to talk nonsense, and went so far that LordRobert at last said, as I was on the spot there was no reason whythey should not be married if the queen pleased.293. Cf. Purgatorio, V. 133:'Ricorditi di me, che son la Pia;Siena mi fe', disfecemi Maremma.'307. V. St. Augustine's Confessions: 'to Carthage then I came, wherea cauldron of unholy loves sang all about mine ears'.308. The complete text of the Buddha's Fire Sermon (which corresponds in importance to the Sermon on the Mount) from whichthese words are taken, will be found translated in the late Hen ryClarke Warren's Buddhism in Translation (Harvard Oriental Seri es).Mr. Warren was one of the great pioneers of Buddhist studies i n theOccident.309. From St. Augustine's Confessions again. The collocation of these two representatives of eastern and western asceticism, as theculmination of this part of the poem, is not an accident.V. WHAT THE THUNDER SAIDIn the first part of Part V three themes are employed: the jour neyto Emmaus, the approach to the Chapel Perilous (see Miss Wes ton'sbook), and the present decay of eastern Europe.357. This is Turdus aonalaschkae pallasii, the hermit-thrush whi ch Ihave heard in Quebec County. Chapman says (Handbook of Bir ds inEastern North America) 'it is most at home in secluded woodla nd andthickety retreats.... Its notes are not remarkable for variety or volume, but in purity and sweetness of tone and exquisite mod ulationthey are unequalled.' Its 'water-dripping song' is justly celebrated.360. The following lines were stimulated by the account of one ofthe Antarctic expeditions (I forget which, but I think one of Shackleton's): it was related that the party of explorers, at the extremity of their strength, had the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted.367–77. Cf. Hermann Hesse, Blick ins Chaos:Schon ist halb Europa, schon ist zumindest der halbe Osten Eu ropasauf dem Wege zum Chaos, fährt betrunken im heiligen Wahn a m Abgrundentlang und singt dazu, singt betrunken und hymnisch wie Dmi triKaramasoff sang. Ueber diese Lieder lacht der Bürger beleidigt, derHeilige und Seher hört sie mit Tränen.401. 'Datta, dayadhvam, damyata' (Give, sympathize, control). T hefable of the meaning of the Thunder is found in the Brihadaran yaka--Upanishad, 5, 1. A translation is found in Deussen's Sechzig Upanishads des Veda, p. 489.407. Cf. Webster, The White Devil, V, vi:...they'll remarryEre the worm pierce your winding-sheet, ere the spiderMake a thin curtain for your epitaphs.411. Cf. Inferno, xxxiii. 46:ed io sentii chiavar l'uscio di sottoall'orribile torre.Also F. H. Bradley, Appearance and Reality, p. 346:My external sensations are no less private to myself than are m ythoughts or my feelings. In either case my experience falls with inmy own circle, a circle closed on the outside; and, with all its elements alike, every sphere is opaque to the others which surr oundit.... In brief, regarded as an existence which appears in a soul, the whole world for each is peculiar and private to that soul.424. V. Weston, From Ritual to Romance; chapter on the Fishe r King.427. V. Purgatorio, xxvi. 148.'Ara vos prec per aquella valor'que vos guida al som de l'escalina,'sovegna vos a temps de ma dolor.'Poi s'ascose nel foco che gli affina.428. V. Pervigilium Veneris. Cf. Philomela in Parts II and III. 429. V. Gerard de Nerval, Sonnet El Desdichado.431. V. Kyd's Spanish Tragedy.433. Shantih. Repeated as here, a formal ending to an Upanishad. 'The Peace which passeth understanding' is a feeble translation of the conduct of this word.三个译本(查良铮、汤永宽、赵萝蕤)之查良铮译《荒原》,并向查老致敬!荒原。

T.S.Eliot艾略特英文介绍

• After a year in Paris, he returned to Harvard to pursue a doctorate in philosophy, but returned to Europe and settled in England in 1914. • The following year, he married Vivienne HaighWood and began working in London, first as a teacher, and later for Lloyd's Bank.

tripleidentitiesotherobservations1917年荒原thewasteland1922年诗集19091925poems190919251925年圣灰星期三ashwednesday1930年老负鼠的猫经oldpossum?sbookpracticalcats1939年焦灼的诺顿burntnorton1941年四个四重奏fourquartets1943年诗集collectedpoems1962年lovesongalfredprufrockmodernistmovement岩石therock1934年cathedral1935年家庭聚会thefamilyreunion1939年鸡尾酒会thecocktailparty1950年老政治家theelderstatesman1958年tripleidentitiessacredwood神木essaysorder风格及秩序论文集elizabethanessays伊丽莎白论文集afterstrangegods拜异教之神influenced1theimagistmovement2thesymbolistmovementarthursymonsenglishcriticmatthewarnoldinfluencemostsuccessfulliterarydictatoramericanliteraryhistorywhowieldedmostdecisiveinfluenceoverliterarydevelopmentlongtime

外国文学第26章《荒原》

11

练习思考题 1.分析《荒原》中的“水”意象,就此写一 篇千字左右的小文章。 2.如何理解杰姆逊所说的“艾略特的诗虽 然是通过零散化效果而起作用,这一首诗却仍然要 求读者能够超越这首诗并且将这些碎片重新组合起 来”? 3.《荒原》原诗稿大约有800行,经庞 德建议删至433行,意图何在? 4.试分析《荒原》的现代性意识。

1

1914年旅欧时遇到埃兹拉· 庞德,经由庞 德引荐,发表了不少诗作,其中最重要的乃是19 15年发表的《普鲁弗洛克的情歌》。1915年 初,艾略特认识了舞蹈家薇薇安· 海伍德(Viv ienHaighWood),两人一见钟情, 于同年6月结婚,然而,罹患精神病症的薇薇安使 整个家庭濒于破裂。迫于生计,艾略特承受着繁重 的工作量,担任某学校讲师的同时还兼任《自我中 心者》(TheEgoist)杂志的助理编辑。 1916年,尽管艾略特完成了博士论文,却因其 拒绝回国未能获得学位。

7

也许我们可以说这首诗以个人的自由为开始, 以对时代的概括为终结。早期的批评家们由于受到 艾略特对《尤利西斯》“神话方法”评论的影响, 强调圣杯传说对全诗结构的重要性;今天的读者会 发现艾略特将伦敦的景物一丝不走样地摄入诗中也 是同样重要的,因为以熟悉的景物为衬托,他可以 加强幻景的力量。。为了反驳艾略特是摧毁传统的 “布尔什维克”诗人这一出现于早期的指控,艾略 特的第一批支持者也许过于强调了这首诗的“秩序 ”和神话结构,而忽略了使《荒原》浑然成为一体 的独特的声音。当弗吉尼亚· 伍尔芙在1922年 下半年某天听艾略特朗诵这首诗时,她说她还不能 “抓住意思”,“只有它的声音在我的耳中回荡 ……但是我喜欢这种声音”。

12

延伸阅读 阿克罗伊德.1989.艾略特传[M]. 刘长缨,等,译,北京:国际文化出版公司. 艾略特.1994.艾略特诗学论文集[M ].李赋宁,译注.天津:百花文艺出版社. 艾略特.1989.艾略特诗学文集[M] .王恩衷,编译.北京:国际文化出版公司.

The Wasteland of T.S.Eliot【艾略特长诗《荒原》的主旨+背景+框架+内容的概括分析】(全英文)

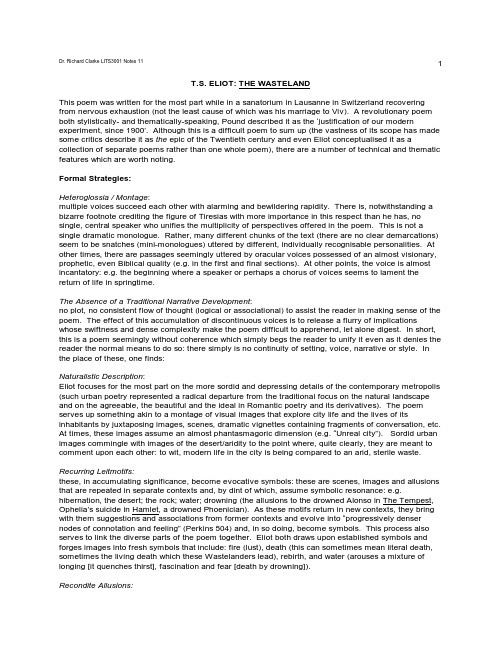

T.S. ELIOT: THE WASTELANDThis poem was written for the most part while in a sanatorium in Lausanne in Switzerland recovering from nervous exhaustion (not the least cause of which was his marriage to Viv). A revolutionary poem both stylistically- and thematically-speaking, Pound described it as the ‘justification of our modern experiment, since 1900’. Although this is a difficult poem to sum up (the vastness of its scope has made some critics describe it as the epic of the Twentieth century and even Eliot conceptualised it as a collection of separate poems rather than one whole poem), there are a number of technical and thematic features which are worth noting.Formal Strategies:Heteroglossia / Montage:multiple voices succeed each other with alarming and bewildering rapidity. There is, notwithstanding a bizarre footnote crediting the figure of Tiresias with more importance in this respect than he has, no single, central speaker who unifies the multiplicity of perspectives offered in the poem. This is not a single dramatic monologue. Rather, many different chunks of the text (there are no clear demarcations) seem to be snatches (mini-monologues) uttered by different, individually recognisable personalities. At other times, there are passages seemingly uttered by oracular voices possessed of an almost visionary, prophetic, even Biblical quality (e.g. in the first and final sections). At other points, the voice is almost incantatory: e.g. the beginning where a speaker or perhaps a chorus of voices seems to lament the return of life in springtime.The Absence of a Traditional Narrative Development:no plot, no consistent flow of thought (logical or associational) to assist the reader in making sense of the poem. The effect of this accumulation of discontinuous voices is to release a flurry of implications whose swiftness and dense complexity make the poem difficult to apprehend, let alone digest. In short, this is a poem seemingly without coherence which simply begs the reader to unify it even as it denies the reader the normal means to do so: there simply is no continuity of setting, voice, narrative or style. In the place of these, one finds:Naturalistic Description:Eliot focuses for the most part on the more sordid and depressing details of the contemporary metropolis (such urban poetry represented a radical departure from the traditional focus on the natural landscape and on the agreeable, the beautiful and the ideal in Romantic poetry and its derivatives). The poem serves up something akin to a montage of visual images that explore city life and the lives of its inhabitants by juxtaposing images, scenes, dramatic vignettes containing fragments of conversation, etc. At times, these images assume an almost phantasmagoric dimension (e.g. “Unreal city”). Sordid urban images commingle with images of the desert/aridity to the point where, quite clearly, they are meant to comment upon each other: to wit, modern life in the city is being compared to an arid, sterile waste. Recurring Leitmotifs:these, in accumulating significance, become evocative symbols: these are scenes, images and allusions that are repeated in separate contexts and, by dint of which, assume symbolic resonance: e.g. hibernation, the desert; the rock; water; drowning (the allusions to the drowned Alonso in The Tempest, Ophelia’s suicide in Hamlet, a drowned Phoenician). As these motifs return in new contexts, they bring with them suggestions and associations from former contexts and evolve into “progressively denser nodes of connotation and feeling” (Perkins 504) and, in so doing, become symbols. This process also serves to link the diverse parts of the poem together. Eliot both draws upon established symbols and forges images into fresh symbols that include: fire (lust), death (this can sometimes mean literal death, sometimes the living death which these Wastelanders lead), rebirth, and water (arouses a mixture of longing [it quenches thirst], fascination and fear [death by drowning]).Recondite Allusions:these are to all sorts of other texts (at least 37) via deliberate echoes of and quotations drawn from other writers. Today, Postmodernists celebrate such pastiche and parody as the basis of all art but many critics of the era saw it as the effect of a lack of creativity. Is The Waste Land the quintessential Modernist/Postmodernist text?Mythological Framework:Eliot, influenced by Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, implicitly alludes to the myth of the dying and reviving god which recurs throughout human civilisation. According to Frazer, primitive man explained the natural diurnal and annual cycles in terms of “the waxing or waning strength of divine beings” and the “marriage, the death and the rebirth of the gods” (qtd. in Perkins, 506). The king was regarded as an incarnation of the fertility of the land: if he weakened or died, the land wasted and would become fertile only when the king was once more healed, resurrected from the dead or succeeded. These ancient fertility myths were incorporated into Christianity. As Perkins puts it,the poem alludes repeatedly to primitive vegetation myths and associates them with theGrail legends and the story of Jesus. In the underlying myth of the poem the land is adry, wintry desert because the king is impotent or dead; if he is healed or resurrectedspring will return, bringing the waters of life. The myth coalesces with the quasi-naturalistic description of the modern, urban world, which is the dry, sterile land. . . . Thepoem does not tell the myths as stories but only alludes to them. . . . (506-7)Eliot’s mythological allusions introduces a semblance of an ordering framework or, for want of a better word, narrative into the poem:[w]hen one knows the plot, one can vaguely integrate some of the episodes of the poemwith it. The fable provides a third language, besides naturalistic presentation andsymbolism, in which the state of affairs can be conceived; the story of the sick king andsterile land is a concrete and imaginative way of speaking of the condition of man. (508)As Eliot put it in a commentary upon Joyce’s Ulysses, the whole apparatus of symbolic and mythological allusion together with the other related narrative techniques served as a way of ‘controlling, of ordering, of giving shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.’ The possibility of regeneration signalled by the myth here may hint at Eliot’s growing interest in Christianity.Overview:The narrative strategies described above are not isolatable from each other. It is impossible to consider the use of symbolism, for example, apart from the use of leitmotifs or the mythological framework. In short, in this poem, the juxtaposition of diverse fragments and strategies serves to make them comment on each other,suggesting manifold, complex and diverse implications. Through symbolism multifariousassociations and connotations were evoked and complexly interwoven. The‘mythological method’ added levels of reference at every point. By allusion, Eliot . . .brought another context to bear on his own, and the parallels and contrasts might offer arich, indefinite ‘vista.’ (513)Some questions arise, though. For example, is The Wasteland one poem or is it several?Content / Themes:The Human Condition:This is summed up in the very title of the poem.Sexuality:The very nature of the myths alluded to has the effect of underscoring the sexual as the source of much of the horrors of life in this wasteland. It is perhaps not accidental that The Wasteland was composed and published in the heyday of Freudian thought. The Wasteland seems to have a special relationship in particular with Freud’s celebrated Civilisation and Its Discontents which was composed in the years leading up to 1930 and which was the crystallisation of much of Freud’s thinking up to this point. Freud’semphasis on the degree to which the harmony of human civilisation was merely a facade, predicated as it is upon the repression of the sexual drive and of aggression (his celebrated conflict between the so-called ‘reality’ and ‘pleasure principles’) is echoed in this poem in which sex, usually in some decadent and sullied form, is almost incessantly evoked (especially in sub-poems II and III). Sex is, indeed, the preoccupation of much of Eliot’s poetry. This is a poem which seems to identify the source of the deadening of moral life and the corruption of civilisation with a perversion of the act of procreation that is synonymous with life itself. This link between Frazer and Freud is directly addressed by Eliot who remarked once that The Golden Bough is a work “of no less importance for our time than the complementary work of Freud--throwing its light on the obscurities of the soul from a different angle”(qtd. in Perkins, 509).Dialectic of Form and Content:Marshall McLuhan once argued that sometimes the ‘medium is the message.’ This is of relevance, arguably, to The Wasteland: Perkins argues that “meanings are ambiguous, emotions ambivalent; the fragments do not make an ordered whole. But precisely this, the poem illustrates, is the human condition” (513). The poem conveys in one vignette after the other, the “sickness of the human spirit”(514), the “weakening of identity and will, of religious faith and moral confidence, the feelings of apathy, loneliness, helplessness, rootlessness, and fear” (514). Thepanoramic range and inclusiveness of the poem, which only Eliot’s fragmentary andelliptical juxtapositions could have achieved so powerfully in a brief work, held in onevision not only contemporary London and Europe but also human life stretching far backinto time. (514)Amidst this welter of confusion, people struggle to make sense of an existence which impedes every attempt to do so. Hence the appropriateness of the end where a “total disintegration is suggested in a jumble . . . of literary quotations” (514).。

瓦伦西亚大学教授如何解读艾略特的长诗《荒原》(全英文)

T. S. Eliot. 2005 (1922): La tierra baldía. Edición bilingüe. Introducción y notas de Viorica Patea. Traducción José Luis Palomares. Madrid: Cátedra, Letras Universales, 2005. 328 pp.Paul Scott DerrickUniversitat de ValènciaPaul.S.Derrick@uv.esIt is practically impossible to overestimate the importance of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), not only in the course of twentieth-century poetry in English, but for Western poetry in general. This single poem has been the object of many hundreds of critical articles and book-length studies. And that interest, that cultural fascination, still shows little sign of diminishing.Along with Pound’s Cantos (begun in 1915), Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), Williams’ Spring and All (1923) and Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), The Waste Land can be classed as one of a handful of ‘centrepiece texts’ of the first-generation Modernist enterprise. It is a masterwork of constructive destruction, a brilliant application of Cubist collage techniques to language. It is both an expression and a demonstration of the cultural malaise and the crisis of belief that resulted from the First World War. It is a profound experiment in the compression, or codification, of an encyclopaedic body of knowledge—as if we had sensed the need at that point in time to condense our heritage into complex, hermetic forms in order to preserve our cultural memory in the face of some impending disaster. But, in addition, it offers a possible therapy for our illness, an opportunity to put a broken world together again—or at least to practice putting it together again. And in this sense, The Waste Land is a powerful record of a yearning for health, wholeness and holiness (words which are all, as Eliot must have been aware, etymologically connected).The poet himself, however, claimed that he had no such exalted aims in mind in 1921 when, trying to recuperate in Margate from the stress contingent on his gradually disintegrating marriage to Vivien Haigh-Wood, he sat down to write what would eventually become part III, “The Fire Sermon”. (He had begun the poem at the end of 1919 as a long series of stylistic parodies with the title “He Do the Police in Different Voices”. He composed the final section, “What the Thunder Said”, in late 1921 in Lausanne, under the care of a pre-Freudian analyst named Roger Vittoz.) In his own, undoubtedly dissembling words, The Waste Land was intended to relieve “a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life” (Eliot 1971: 1). All false modesty aside, the question that immediately arises is: how does an insignificant personal complaint get converted into such an astounding religious, philosophical and literary accomplishment?Providing a credible account of such a complicated process might be compared to producing a high-resolution, three-dimensional, multi-sectional holographic map of the occult intestines of the Gordian Knot. But that’s what this edition does. The personal aspects of The Waste Land’s genesis, the stages of its development, its roots in Eliot’s previous experience, the warp and woof of its incredible texture and much much more are masterfully illuminated in Viorica Patea’s lengthy and well-written142Paul Scott Derrick Introduction to this new translation of The Waste Land into Spanish. There seem to be very few of those hundreds of studies the poem has inspired that she is not aware of.It first appeared in the London journal Criterion, in October 1922. It was published one month later in New York in The Dial. For reasons that Eliot never made clear, he decided to append those famous notes to each of the poem’s five sections for its first edition in book form (New York: Boni and Liveright, [December] 1922). Did he do so simply for commercial reasons, to make the book longer? Did he feel the need to protect himself against possible claims of plagiarism? Was it part of the overall strategy of Modernism to present its practitioners as connoisseurs, a subterfuge by which the Modernist poet distinguished himself from the sentimentality of many fin-de-siècle versifiers and emphasized his ‘professionalism’?Or was it a sincere attempt at explanation, to make the poem accessible to more than an elite coterie of privileged readers? Whatever the motives may have been, those notes have raised more questions for serious students of Eliot’s work than they answer and have notoriously become an integral factor in the poem’s lasting fascination.But of course it was not Eliot’s duty, or intention, really to explain his own poem to the public. That is a task for those of us who follow. In this edition, Dr. Patea, Senior Lecturer in American literature at the University of Salamanca and a specialist in Modernist poetry, elucidates the meaning and significance of The Waste Land just about as thoroughly and effectively as it seems possible to do.The book consists of three general sections. The first, the Introduction, provides us with a wealth of background material which is an indispensable aid for an appreciative reading of the text. The second one is a meticulously annotated bi-lingual edition of the poem itself, and its notes, with a translation by José Luis Palomares. And the third, an extremely helpful addition, is an Appendix of ten short texts (1-2 pages), also in bi-lingual format, which are among the most important of The Waste Land’s cornucopia of intertextual references.The Introduction, also structured in three sections, is a well-balanced mix of biographical information and critical assessment of Eliot’s thought and work. This kind of approach is always enlightening, but especially so in the case of an author who went to such extremes to obfuscate the many traces of his personal life that inform his work. We learn about Eliot’s New England family background, and the atmosphere surrounding his childhood; the influence of Irving Babbit and George Santayana during his undergraduate years at Harvard and the early but lasting literary influence of Baudelaire, French Symbolism and the work of Dante.Few readers beyond specialized academic circles are aware that Eliot carried out his graduate studies at Harvard in philosophy. Dr. Patea provides a very informative discussion of this fundamental period in his intellectual development, pointing out the importance for him of teachers such as Josiah Royce, William James, Bertrand Russell and, above all, the subject of his doctoral dissertation (which he completed but, because of the First World War, never defended), the English idealist philosopher F. H. Bradley. Patea is especially effective in signalling the impact of Bradley’s philosophy on Eliot’s poetry and tracing Bradley’s imprint in The Waste Land. This very complex aspect of the poem was first seriously considered by Anne C. Bolgan (1973), who rediscovered Eliot’s dissertation in the Pusey Library at Harvard. Since then, few commentators haveReviews 143 failed at least to mention Bradley, although the most satisfying studies in this respect are probably still those of Schusterman (1988) and Jain (1992).We are also given a good overview of Eliot’s earliest critical essays and how they are intimately linked with the content of the papers he wrote for many of his graduate courses in philosophy, as well as a survey of the development of his poetry and criticism over the course of his life.The second part of the Introduction offers a panorama of detailed information concerning The Waste Land itself and discusses the most important influences contributing to its innovative form and breathtaking scope. We are given a fine description of Ezra Pound’s incisive editorial work. In convincing Eliot to cut out more than 40% of the original text, Pound ensured not only a tighter and stronger organization and a more allusive and esoteric quality, but also a higher degree of Cubist fragmentation. Patea explains how Eliot discovered what he described as ‘the mythical method’—which defines his use of history in the poem—in his own reading of Joyce’s recently-published Ulysses. She also gives a clear account of the use Eliot made of Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance and James Frazer’s The Golden Bough. Because Eliot directly cited these two works in the introductory paragraph of his notes to the poem, their importance is undeniable (regardless of what his motives for appending that material may have been). Patea’s Introduction, however, places them in a much more balanced perspective than usual, within the framework of the mythical method, among a larger number of literary, religious, anthropological and psychological influences.Finally, the third part of the Introduction devotes just over 75 pages to a detailed, insightful and coherent close reading of the poem. Many ingenious metaphors have been invented to illustrate what happens in The Waste Land. My own personal choice is the archaeological site. The ultimate grace of the Eliot/Pound collage technique is that it confronts us with a field of confusing fragments that we need to reconstruct, fragments that happen to be the remains of earlier cultural continuities:the various traditions of the West, primitivism and the wisdom of the East. This act of reconstruction corresponds with the final phase of the Cubist aesthetics. After the painter has analyzed a scene, taken it apart and placed the pieces into a new design, the viewer must complete the process by recreating the original scene (or stimulus) from the confusing cues the painting provides. In the case of The Waste Land though, the original scene, or stimulus, is the whole expanse of Western culture. The reader, like an archaeologist at a dig, is forced to use every bit of intelligence, imagination and knowledge at his or her command to flesh out those fragments, reconstitute them and to recover, or maybe better, recreate the historical continuity those fragments are remnants of. There can be a virtually unlimited number of coherent and valid explications of the poem. But every one of them is, in effect, an individual step toward recovering the health—or the wholeness—of the waste land of Western society. In her particular unfolding of this enigmatic complex of language and cultural memory (and forgetfulness), Dr. Patea applies a fine imagination and a generous intelligence to the large body of knowledge that the first two sections of her essay display.The Waste Land ends with an appeal to Buddhist and Hindu scriptures as offering a possible model for a cure to the spiritual aridity that is destroying the West:144Paul Scott Derrick con estos fragmentos a salvo apuntalé mis ruinasSea, pues, que habré de obligaros. Hierónimo esta furioso otra vez.Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.Shanti shanti shanti (285)The poem itself, in spite of its apparently chaotic fragmentation and pervasive air of pessimism, constitutes a journey from despair to hope. “La tierra baldía acaba”, writes Patea,con un atisbo de lo trascendente y la aceptación de lo sagrado. [. . .] La verdad revelada conduce a la conciencia lírica a la realidad de lo inexpresable “donde el significado aún persiste aunque las palabras fallan” [. . .] El poema de Eliot traza el viaje del alma a través del desierto de la ignorancia, del sufrimiento y de la sed de las aspiraciones terrenales.Concluye con la revelación de una realidad que libera su condición fragmentada. En el misterio de la contemplación el ser intuye la plenitud de este estado de conciencia no dual y no objetivable. (170-71)It is probably true that it began as an attempt to relieve “a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life” (Eliot 1971: 1). But Eliot is an artist whose individual mind came to accommodate the collective mind of his culture. This is an artist who taught himself to write, as he describes it in his early essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, “not only with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order” (Eliot 1964: 4).His ‘insignificant grouse’ therefore inevitably transcends to a universal plane. The Waste Land is a prototype of the verbal collage, a case study of Eliot’s concept of the historical consciousness and the mythical method. It can be thought of as a puzzle to be solved, in which we solve—or resolve—ourselves. Or it might be thought of as a verbal field containing relics of all that we are losing—fragments, mixing memory and desire, forgetfulness and need, pointing us the way toward a new sense of wholeness.Several worthwhile contributions to the general field of Eliot studies have been published in Spain (Gibert 1983; Abad 1992; Zambrano Carballo 1996; Vericat 2004), each one commendable in its own way. But this edition of The Waste Land seems to me to offer Spanish readers the best opportunity to appreciate and to comprehend all of the manifold dimensions of this towering signpost to the Modern (and post-modern) condition.Works CitedAbad, Pilar 1992: Cómo leer a T. S. Eliot. Madrid: Júcar.Bolgan, Anne C. 1973: What the Thunder Really Said: A Retrospective Essay on the Making of “The Waste Land”. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP.Eliot, T. S. 1964: Selected Essays. New York: Harcourt Brace & World, Inc.———— 1971: The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound. Ed. Valerie Eliot. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.Reviews 145 Fraser, James George 1922: The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, Abridged ed. New York: The MacMillan Co.Gibert Maceda, María Teresa 1983: Fuentes literarias en la poesía de T. S. Eliot. Madrid: Ediciones de la Universidad Complutense.Jain, Manju 1992: T. S. Eliot and American Philosophy: The Harvard Years. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.Schusterman, Richard 1988: T. S. Eliot and the Philosophy of Criticism. New York: Columbia UP. Vericat, Fabio 2004: From Physics to Metaphysics: Philosophy and Allegory in the Critical Writings of T. S. Eliot. Valencia: Universitat de València, Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans.Weston, Jesse 1983 (1919): From Ritual to Romance. Gloucester MA: Peter Smith.Zambrano Carballo, Pablo 1996: La mística de la noche oscura: San Juan de la Cruz y T. S. Eliot.Huelva: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva.Received 20 May 2006Revised version received 5 October 2006。

艾略特的诗歌作品有

艾略特的诗歌作品有艾略特(T.S. Eliot)是20世纪最重要的英语诗人之一,他的诗歌作品以其深刻的思想、复杂的结构和独特的风格而闻名。

以下是一些艾略特的著名诗歌作品:1. 《荒原》(The Waste Land),这是艾略特最著名的诗歌作品之一,被认为是现代主义诗歌的里程碑之一。

它探讨了战争、文化破碎、人类孤独等主题,运用了多种语言和文化的引用,形成了复杂的叙事结构。

2. 《四个四重奏》(Four Quartets),这是艾略特的一系列长诗作品,包括《燃烧的草》(Burnt Norton)、《东风》(East Coker)、《干旱之地》(The Dry Salvages)和《小吉尔斯》(Little Gidding)。

这些作品探讨了时间、信仰、人类存在等主题,被认为是艾略特晚年创作的巅峰之作。

3. 《愚人之歌》(The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock),这首诗以第一人称的形式讲述了一个中年男子的内心独白,探讨了生活的空虚、自我怀疑和社交焦虑等主题。

它被认为是现代主义诗歌的经典之作。

4. 《亚伯拉罕之书》(The Book of Abraham),这是艾略特早期的一部叙事诗,以宗教和神话的元素为基础,探讨了个人的信仰和灵性追求。

5. 《灰烬》(Ash Wednesday),这是艾略特在转向天主教之后创作的一部长诗,探讨了信仰、救赎和灵性的主题。

除了以上列举的作品,艾略特还有许多其他诗歌作品,如《普鲁士的死人》(The Dead Prussian)、《马克斯·贝尔曼的诗》(The Poetry of Max Beerbohm)等。

他的诗歌作品风格多样,包括现代主义的实验性写作、宗教和神秘主题的探索,以及对社会和人类存在的深入思考。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

Spread out in fiery points

Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

In vials of ivory and coloured glass

Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfume

Unguent, powdered, or liquid--troubled, vondused

And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

The change of Philomel, by the barbarous king

So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: 'Stetson!

'You who were with me in the ships at Mylae

Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

One must be so careful these days.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

The Waste Land

"NAM Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse

oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum

illi pueri dicerunt:

Sebulla pe theleis;

respondebat illa:

apothanein thelo."

'That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

'Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

'Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

'O keep the Dog far hence, that's friend to men,

I will show you fear in a handfull of dust.

Frish weht der Wind

Der Heimat zu

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

'You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

They called me the hyacinth girl.'

And when we were children, staying at the arch-duke's,

My cousin's, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

Oed'und leer das Meer.

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

'Jug Jug' to dirty ears.

And other withered stumps of time

Were told upon the walls; staring forms

Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

Doubled the flames of seven-branched candleabra

Reflecting light upon the table as

The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

From satin cases poured in rich profusion.

You canot say, or guess, for yoen images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm' aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

The lady of situations.

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

I think we are in rat's alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

'What is that noise?'

The wind under the door.

'What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?'

Glowed on the marble, where the glass

Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

From which a golden Cupidon peeped out

(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

--Yet when we came back, late, from the hyacinth garden,

Your arms full and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

With a wicked pack of cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

'Or with his nails he'll dig it up again!

'You! hypocrite lecteur!--mon semblable,--mon frere!'