2012 系统综述与荟萃分析.

第七章系统评价的方法与评价原则2012

(二)检索文献

系统、全面地收集所有相关的文献资料是系统评价与叙述性文献 综述的重要区别之一。为了避免出版偏倚和语言偏倚,应围绕要解决 的问题,按照计划书中制订的检索策略(包括检索工具及每一检索工 具的检索方法),采用多种渠道和系统的检索方法。除发表的原著之 外,还应收集其他尚未发表的内部资料以及多语种的相关资料。 除了利用文献检索的期刊工具及电子光盘检索工具(Medline、 Embase、Scisearch、Registers of clinical trials)外,系统评价还强调 通过与同事、专家和药厂联系以获得未发表的文献资料如学术报告、 会议论文集或毕业论文等;对已发表的文章,由Cochrane协作网的工 作人员采用计算机检索和手工检索联合的方法查寻所有的随机对照试 验,建立了Cochrane对照试验注册库和各专业评价小组对照试验注册 库,既可弥补检索工具如MEDLINE等标识RCT不完全的问题,也有 助于系统评价者快速、全面获得相关的原始文献资料。

性的作用。

系统评价本身只不过是一种研究的方法学,并不仅限于随机对照试验或 仅对治疗措施疗效进行系统评价。 根据研究的临床问题不同,系统评价可分为病因、诊断、治疗、预后、 卫生经济评价和定性研究等方面的系统评价; 根据系统评价纳入的原始研究类型不同,可分为临床对照试验和观察性 研究的系统评价,前者如随机对照试验和非随机对照试验的系统评价,后者 如队列研究和病例-对照研究的系统评价; 根据进行系统评价时纳入原始研究的方式,可分为前瞻性、回顾性和累 积性系统评价; 根据资料分析时是否采用统计学方法(Meta-分析),可分为定性和定 量的系统评价。 目前,由于根据随机对照试验所进行的系统评价在理论和方法学上较完 善及其论证强度较高,所以有关随机对照试验或评估治疗措施疗效的系统评 价较多,而其他类型的系统评价如诊断试验、病因学研究、非随机试验等正 在研究之中。

第五章 系统综述

统综述至少由两名人员独立完成筛选研究和提取

资料以保证数据的真实性。

3. Cochrane系统综述的作者需具备良好的英文阅 读与写作能力并熟悉RevMan软件的使用方法。 Cochrane系统综述研究方案和全文有统一的格式并 均需在RevMan软件中用英文写作及进行编辑管理。 4. 查询注册情况。 使用系统综述课题管理库 (RevMan Title Manager)网站查询拟注册题目是 否已被注册以避免重复工作。 5. 安排工作时间。 完成一篇Cochrane注册的系统 综述大概需要专职工作12~18个月。

能有效说明问题;但当研究间存在较大的异质性,

不能进行合并分析,即使合并也难以解释,特别 是当研究数据不完整时,Meta分析无法进行。

第二节

系统综述设计与实施

不同的学术组织对系统综述有不同的 要求和规定,Cochrane系统综述有非常严 格的制作程序和要求,是循证医学高级别 证据之一,下面以Cochrane系统综述为例 说明设计与实施过程。

发生率,你查寻了有关资料,发现有7个高质量的

随机对照试验,其中5个试验结果为阴性(使用激 素后未能减少早产儿的死亡率和呼吸窘迫综合征 的发生率),2个试验结果为阳性,你将作何结论?

第一节 概述

一、概念、特点和类型 (一)概念

1.综述(review) 综述是指就某一时间内,针 对某一专题,对大量原始研究论文中的数据、资料和 主要观点进行归纳整理、分析提炼而写成的论文。它 属于二次研究文献,专题性强,涉及范围较小,具有 一定的深度和时间性,能反映出这一专题的历史背景、 研究现状和发展趋势,具有较高的情报学价值。

干预措施的利弊,或在临床应用过程中存在较大

争议的问题。 2.必要性 系统综述关注的临床问题应具有研究

系统评价、Meta(荟萃)分析及传统综述

系统评价、Meta(荟萃)分析及传统综述系统评价是一种按照既定纳入标准广泛收集某医疗卫生问题的相关研究,是严格评价其质量,并进行定量合并分析或定性分析,得出综合结论的研究方法。

系统评价、Meta(荟萃)分析及传统综述三者都属于观察性研究。

1.传统综述是一种定性描述的研究方法,根据作者对某领域基础理论的认识和相关学科的了解,回顾分析该领域某段时期的研究文献,评价研究结果的价值和意义,发现存在的问题,为将来的研究方向提出建议,使读者能在短时间内了解该领域研究的历史、现状和发展趋势。

传统综述的写作没有固定的格式和规程,也没有评价纳入研究质量的统一标准,其质量高低受作者专业水平、资料收集广度及纳入文献质量的影响很大,不能定量分析干预措施的总效应量。

不同作者对同一问题的研究很可能得出完全不同的结论。

2.Meta分析是一种将多项研究结果进行定量合成分析的统计学方法,始于20世纪70~80年代,最初被定义为“收集大量单项试验进行结果整合的统计学分析”;1991年,Fleiss提出了较严谨和准确的定义,“Meta分析是用于比较和综合针对同一科学问题研究结果的统计学方法,其结论是否有意义取决于纳入研究的质量”。

这说明并非所有Meta分析都能得出高质量结果和结论,只有对纳入研究进行同质性检验,分析异质性的原因,按同质性因素进行合并的Meta分析才可能有意义。

仅纳入随机对照试验(RCT)的Meta分析得出的结果一般偏倚较小,其结论准确性远比单项试验高。

3.系统评价卫生政策决策者、医师和患者在决策时必须以高质量信息为依据,但面对大量医疗卫生信息时常难选择,因为多数信息都存在或多或少的问题,有的甚至是错误信息。

另一方面,由于全球医疗卫生信息更新极快,受时间、精力及检索技能等条件限制,大量有价值的信息被埋没浪费;RCT由于严格采取了控制偏倚的措施,可靠性通常较其他试验方法高,但受环境条件限制,很多RCT样本量太小,不能有效克服机遇的影响,或只专注于某特定问题,导致实用性受限。

荟萃分析

荟萃分析百科名片荟萃分析,又称“Meta 分析”,Meta意指较晚出现的更为综合的事物,而且通常用于命名一个新的相关的并对原始学科进行评论的学问,不但包括数据结合,而且包括结果的流行病学探索和评价,以原始研究的发现取代个体作为分析实体。

荟萃分析产生的主要的理由是:对于多个单独进行的研究而言,许多观察组样本过小,难以产生任何明确意见。

目录荟萃分析-概述荟萃分析-荟萃分析的分类荟萃分析-IPD 荟萃分析的步骤荟萃分析-荟萃分析的优劣荟萃分析-荟萃分析的未来荟萃分析-概述荟萃分析-荟萃分析的分类荟萃分析-IPD 荟萃分析的步骤荟萃分析-荟萃分析的优劣荟萃分析-荟萃分析的未来展开编辑本段荟萃分析-概述荟萃分析的概念最早是由Light 和Smith 于1971 年提出的。

当时针对大量发表的科学论文中,对于同样的研究却得出截然不同的结果的问题,他们提出应该在全世界范围内收集对某一疾病各种疗法的小样本、单个临床试验的结果,对其进行系统评价和统计分析,将尽可能真实的科学结论及时提供给社会和临床医师,以促进推广真正有效的治疗手段,摈弃尚无依据的无效的甚至是有害的方法。

1976 年Glass 首次将这一概念命名为Meta-analysis(荟萃分析),并定义为一种对不同研究结果进行收集、合并及统计分析的方法。

这种方法逐渐发展成为一门新兴学科--“循证医学”的主要内容和研究手段。

荟萃分析的主要目的是将以往的研究结果更为客观的综合反映出来。

研究者并不进行原始的研究,而是将研究已获得的结果进行综合分析。

编辑本段荟萃分析-荟萃分析的分类通常概念下的文献综述是对有关文献的内容或结果进行罗列、简单的描述和初步的讨论,而荟萃分析则完全上了一个台阶。

根据荟萃分析所依据的基础或数据来源可以将其分为三类:文献结果荟萃分析(Meta-analysis based on literature, MAL);综合或合并数据荟萃分析(Meta-analysis based on summary data, MAS);独立研究原始数据荟萃分析(Meta-analysis based on individual patient data, MAP or IPD Meta-analysis)。

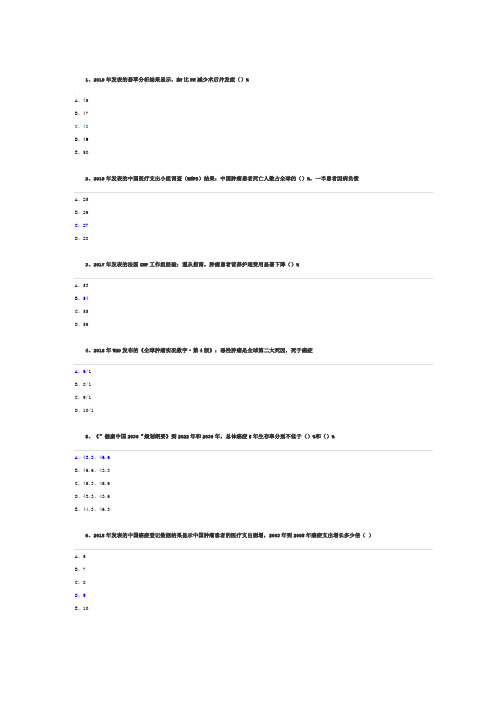

职业资格考试及答案-肿瘤学

1、2019年发表的荟萃分析结果显示,EN比PN减少术后并发症()%A、46B、47C、48D、49E、502、2019年发表的中国医疗支出小组调查(MEPS)结果:中国肿瘤患者死亡人数占全球的()%,一半患者因病负债A、25B、26C、27D、283、2017年发表的法国CNP工作组经验:遵从指南,肿瘤患者营养护理费用显著下降()%A、53B、54C、55D、564、2018年WHO发布的《全球肿瘤实况数字·第4版》:恶性肿瘤是全球第二大死因,死于癌症A、6/1B、8/1C、9/1D、10/15、《”健康中国2030“规划纲要》到2022年和2030年,总体癌症5年生存率分别不低于()%和()%A、43.3、46.6B、46.6、43.3C、46.3、46.6D、43.3、43.6E、44.3、46.36、2018年发表的中国癌症登记数据结果显示中国肿瘤患者的医疗支出剧增,2003年到2005年癌症支出增长多少倍()A、6B、7C、8D、9E、101、2021年最新发表的ESPEN《肿瘤患者临床营养实用指南》推荐:肿瘤患者的营养治疗,首选()A、肠内营养B、ONSC、肠外营养D、营养咨询2、2021年最新发表的ESPEN《肿瘤患者临床营养实用指南》推荐:放疗患者的营养治疗,首选()A、ONS/ENB、肠内营养C、肠外营养D、营养咨询3、2017年发表的法国研究结果:()%的患者不规范使用肠外营养(不符合指南标准)A、65B、70C、75D、804、化疗开始至结束,全程给予ONS ,按计划化疗完成率()A、70%B、80%C、90%D、100%E、50%5、2020年发表的意大利肿瘤学会(AIOM)的全国调研:()肿瘤科医护人员依从指南进行营养筛查和评估A、1/3B、1/4C、1/5D、1/66、美国临床肿瘤学会临床建议:()与抗肿瘤标准治疗必须整合 ??A、营养治疗B、放疗C、化疗D、手术E、检查1、营养状况评定可以测量人体的()A、体重B、体质量指数C、皮褶厚度和臂围D、以上均是2、化疗开始至结束,全程给予ONS ,按计划化疗完成率()%A、70B、80C、90D、1003、2017年发表的研究结果,法国CNP项目的实施:肿瘤患者营养护理费用显著下降()%A、53B、54C、55D、564、肠内营养常见的并发症包括()A、机械性并发症B、胃肠道并发症C、感染性并发症D、以上均是5、肠内营养的优点包括()A、符合生理状态,能维持肠道结构和功能的完整B、费用低,使用和监护简便C、并发症较少D、以上均是6、美国临床肿瘤学会临床建议:()与抗肿瘤标准治疗必须整合A、营养治疗B、放疗C、化疗D、手术1、营养治疗的第五阶梯是()A、饮食+营养教育B、全肠内营养(TEN)C、饮食+口服营养补充剂(ONS)D、全肠外营养(TPN)2、2018年发表的中国临床研究结果:34%肿瘤患者未能达到目标摄入量的()%A、40B、50C、60D、703、国内外相关指南推荐每日能量摄入量目标:()kcal/kg/天A、20-25B、25-30C、30-35D、35-404、每日蛋白质摄入量目标:()克/kg/天A、0.5-1.0B、1.0-2.0C、2.0-2.5D、2.5-3.05、化疗开始至结束,全程给予ONS ,按计划化疗完成率()A、70%B、80%C、90%D、100%E、50%6、美国临床肿瘤学会临床建议:()与抗肿瘤标准治疗必须整合 ??A、营养治疗B、放疗C、化疗D、手术E、检查1、ESPEN、CSPEN等国内外所有营养指南均推荐:围化疗期,优先选择()A、营养咨询B、口服营养补充剂(ONS)C、肠外营养D、营养风险筛查2、每日能量摄入目标:2018年发表的系统综述结果:结直肠癌术前ONS作为预康复措施的依从性为()A、40~100%B、50~100%C、60~100%D、70~100%3、2005年发表的综述描述:()是癌症患者对食物和饮食失去兴趣的主要原因A、听觉改变B、视觉改变C、味觉改变D、并发症4、术后化疗全程给予ONS,按计划化疗完成率%A、70B、80C、90D、1005、有口腔黏膜炎者,建议(),以减轻因ONS刺激粘膜所致的疼痛感A、更换制剂种类B、在ONS中加入增稠剂C、服用冰凉的ONS制剂D、少量多餐E、按摩腹部6、2012年发表的系统综述结果:口服营养补充剂的依从耐受性差,住院患者仅有()%A、67B、68C、69D、701、早期肠内营养支持优点包括()A、可以直接被肠胃肠道吸收利用B、给药途径方便C、治疗费用较低D、以上都是2、肠内营养腹泻相关的治疗和处理措施不正确的是()A、应用益生菌B、增加脂肪摄入C、应用抗生素D、注意肠内营养物的浓度3、引起恶心、呕吐的原因包括()A、营养液的高渗透压导致胃潴留B、乳糖不能耐受C、输注速度过快D、以上均是4、因肠内营养物本身使用引起腹泻的原因包括()A、营养液供给量大,速度快B、细菌污染C、肠内营养物配方含高脂肪D、以上都是5、肠内营养前后每()要用温水来冲洗管道A、2hB、4hC、6hD、12h6、肠内营养常见并发症()A、腹泻B、误吸C、腹胀D、以上都是1、胃肠外科手术患者术前口服肠内营养补充剂()A、有助于改善术后免疫功能B、有助于改善营养状态C、降低炎症因子水平D、促进术后肠道功能的恢复E、以上都是2、消化液回输的目的()A、有利于维持机体内环境的稳定性B、增加患者对肠内营养液的耐受性,使营养物质吸收更趋完善C、维持瘘口远端肠道黏膜细胞结构和功能的完整性,保持肠黏膜屏障,减少肠源性感染D、刺激肠蠕动,加速肛门排气时间E、以上都是3、关于消化液收集方法,叙述正确的是()A、管状瘘可采用普通造口袋收集B、唇状瘘可采用普通引流袋收集C、管状瘘可采用普通引流袋收集D、根据消化液吸收性质可选择开放间断式或者密闭持续式收集方法4、患者术前饮用糖类饮料,麻醉前()仍可进食固体食物A、2hB、4hC、6hD、12hE、24h5、下列关于快速康复护理,叙述错误的是()A、有效加快了患者机体功能的恢复,改善预后B、通过多种外科护理措施综合治疗C、更注重术中麻醉的管理D、实现了快速术后止痛和胃肠道功能恢复6、术后()左右可以让患者进食流质食物,根据恢复时间逐渐增加食物摄入量A、2hB、4hC、6hD、12hE、24h1、正常胃排空约需()h左右A、2B、6C、8D、12E、242、肠内营养腹泻相关的治疗和处理措施不正确的是()A、应用益生菌B、增加脂肪摄入C、应用抗生素D、注意肠内营养物的浓度3、不属于疾病相关因素引起腹泻的是()A、吸收障碍B、感染C、高血压D、糖尿病4、关于肠内营养管冲管要点说法正确的是()A、间歇重力滴注或分次推注者,应每次喂养前后用20-30ml温开水脉冲式冲管B、每次给药前后和胃残余量检测后,应用20-30ml温开水脉冲式冲管C、免疫功能受损或危重患者,宜用灭菌注射用水冲管D、应避免使用PH≤5的酸性液体药物与营养液混合E、以上都是5、肠内营养前后每()要用温水来冲洗管道A、2hB、4hC、6hD、12h6、早期肠内营养支持优点包括()A、可以直接被肠胃肠道吸收利用B、给药途径方便C、治疗费用较低D、以上都是1、根据SGA法,营养状况正常的是()A、膳食摄入量<70%,腹水和消化道症状显著B、65%≤膳食摄入<80%,皮下脂肪和体力下降C、70%≤膳食摄入<95%,有轻微腹水和消化道症状D、膳食摄入≥90%需要量,无腹水和消化道症状2、重度营养不良术后给予外周静脉营养支持,每()评价一次A、1dB、2dC、3dD、7d3、营养风险筛查表结果分数为( ),即为存在营养风险A、≥3B、3~5C、5~8D、9~104、营养风险筛查表,下列哪项是加分项()A、女性B、12岁以下儿童C、免疫力低下者D、年龄≥70岁5、营养风险筛查表不包括()A、疾病严重程度B、围术期状态C、营养状态D、年龄6、麻醉清醒后,()进食半流质食物1500mlA、8小时B、24小时C、48小时D、72小时1、患者自我营养评估内容包括()A、体重变化B、摄食情况的改变C、与消化道相关的症状D、活动和身体功能E、以上均是2、术前营养支持强调蛋白质补充,有利于术后恢复,建议非肿瘤患者术前每餐保证≥()g的蛋白质摄入A、9B、12C、18D、25E、303、加速康复外科理念(ERAS)以循证医学证据为基础,通过()等多科室协作,对围术期处理的临床路径予以优化,从而缓解围术期应激反应,减少术后并发症,缩短住院时间,促进病人康复A、外科B、麻醉C、护理D、营养E、以上均是4、营养不良的五阶梯治疗中当下一阶梯无法满足患者() %营养目标需求量3-5天时,应该选择下一阶梯A、40B、50C、60D、70E、805、营养不良的后果包括()A、ICU停留时间增长B、住院天数增加C、医疗费用增加D、并发症风险增加E、以上均是6、围术期营养不良患者推荐使用ONS≥()dA、3B、7C、12D、14E、211、在影像学检查中,()具有诊断和治疗的双重作用A、MRIB、CT淋巴管造影C、淋巴管造影D、上腹部CTE、淋巴核素显像2、乳糜漏是由于胸导管或淋巴管主要分支破损或渗透性过高引起乳糜液溢出的一种疾病,可出现()等A、严重的低蛋白血症B、脂溶性维生素缺乏C、能量-蛋白质营养不良D、酸中毒和免疫功能障碍E、以上都是3、关于乳糜漏的临床表现,错误的是()A、乳糜性胸腔积液B、蛋白尿C、乳糜性腹水D、乳糜尿E、乳糜样腹泻4、乳糜漏保守治疗无效可考虑()A、禁食B、手术治疗C、引流D、纠正低蛋白血症E、饮食控制5、在乳糜漏的影像学检查中,下面哪项不属于特殊检查()A、淋巴管造影B、淋巴核素显像C、MRID、CT淋巴管造影6、乳糜漏的病因分类,根据发生部位的不同分为()A、乳糜胸B、乳糜腹C、乳糜泻D、乳糜尿、软食的适应症要求()A、食物残渣较少B、便于咀嚼C、易消化D、不宜油炸、油煎E、以上均是2、肠外营养液配置好暂不使用,应放在4°冰箱内保存,保存时间不超过()小时A、12B、24C、36D、48E、723、半流质饮食适应症要求()A、少量多餐B、注意营养素供给C、2~3小时进食1次D、每天进食6~8次E、以上均是4、普食适应症不包括()A、非消化道肿瘤或无消化系统功能障碍的病人B、伴有口腔疾患的肿瘤病人C、化疗、放疗前后的病人D、术后康复期病人E、不伴有发热、出血等临床急性期症状的病人5、再喂养综合征临床表现是()A、低磷血症、低钾血症、低镁血症B、低磷血症、高钾血症、低镁血症C、低磷血症、低钾血症、低钠血症D、低磷血症、高钾血症、高镁血症E、高磷血症、高钾血症、低镁血症6、肿瘤病人营养不良相关的因素包括()A、能量代谢异常B、蛋白质代谢异常D、脂代谢异常E、以上均是1、下列属于CRRT主要优势的是()A、精确调控液体平衡B、对心血管功能的影响小C、维持机体内环境稳定D、以上均是2、下列对CRRT对机体营养代谢的影响中不属于蛋白质的影响的是()A、CRRT治疗失血B、CRRT时,谷氨酰胺的清除要比其他氨基酸更加明显C、CRRT激活细胞因子,使机体处于类似于慢性炎症反应状态D、CRRT治疗氨基酸很容易被滤器所清除3、下列属于CRRT对机体营养代谢的影响中脂类的是()A、脂肪不经CRRT滤过,不需额外补充B、CRRT时可显著引起葡萄糖获得或丢失C、采用不含糖或糖含量低的置换液D、使用含1%或更高的葡萄糖置换液可以导致机体净摄取葡萄糖4、下列不属于CRRT特点的是()A、溶质清除率低B、血流动力学稳定C、纠正酸碱平衡紊乱D、代谢控制5、下列对AKI/ARF患者代谢变化描述错误的是()A、排泄减少,导致血电解质增加B、微量元素和维生素缺乏C、钾、镁、磷酸氢盐减少D、以上均是6、下列对于主观全面评价量表(SGA)描述正确的是()A、SGA是一个可重复的、有效的评价患者营养状态的指标B、SGA包括最近体重和营养摄入的变化、胃肠道症状C、SGA经济、检测迅速、对蛋白质能量营养状态能进行综合评估D、以上均是。

荟萃分析

1.效应量的选择和各独立研究的效应大小的计算 1)效应量的选择 效应量(effect size / ES):定量测量一种 因素与另一因素之间关联强度的统计量。 ① 二分类变量:比值比(OR),绝对危险度 (AR);相对危险度(RR);风险差(RD)等。 ② 连续变量:加权均差(WMD);标准化均差 (SMD);Hedges’g等。

17

3.异质性(heterogeneity)检测。 异质性检测目的:检查各个独立研究的结果是 否具有可合并性。异质性的存在将影响合并结果的 可信度。 若异质性小,说明各独立实验基本上是在同样 的条件下进行,数据较为均一,结果的差异主要由 随机因素产生。 若异质性大,说明各实验数据差异较大,各实 验中除了随机性因素外,还可能存在其他导致结果 不一致的因素。

21

异质性检的测结果和处理方法。 1)若异质性不明显,则选择固定效应模型来 合并效应值。 2)若异质性明显,则应选择随机效应模型来 合并效应值,并且通常需要进一步同过亚组分析和 荟萃回归分析来探讨异质性的来源。 3)当异质性过于明显且不能排除,也不能弄 清楚来源时,则应放弃荟萃分析,只做一般的定性 描述 。

13

OR值所代表的意义 <1:病例组所施加的因素使暴露事件发 生的机会减少; =1:病例组施加的因素对暴露事件没有 影响; >1:病例组所施加的因素使暴露事件发 生的机会增加。

OR

例如,前面OR=0.80,则说明吸烟使晚绝经的 机会减少到80%。也就是吸烟使绝经年龄提前。

14

②连续型变量效应量的计算(基于标准化均数差 / SMD的 Hedges’g ) X1:病例组平均值 SMD=(X1-X2)/S X2:对照组平均值 N1:病例组样变量 N2:对照组样本量 S :总的标准差 S1:病例组标准差 S2:对照组标准差 Hedges’g=SMD*J J :校正因子 J=1-[3/4*(N1+ N2-3)]

高同型半胱氨酸血症对认知功能障碍影响的相关研究进展

高同型半胱氨酸血症对认知功能障碍影响的相关研究进展【摘要】同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,Hcy)是氨基酸代谢的中间产物,由甲硫氨酸、半胱氨酸分解过程中产生。

体内代谢失衡,血清同型半胱氨酸>15umol/L时可诊断为高同型半胱氨酸血症(HHcy)。

叶酸、维生素B12、维生素B6缺乏可能会引起同型半胱氨酸升高。

而高同型半胱氨酸血症会增加认知功能障碍发生的风险,目前具体作用机制尚不明确。

尽管有研究证明,通过补充叶酸、维生素B6、维生素B12可以治疗高同型半胱氨酸血症,但是没有强有力证据证明通过补充维生素等微量元素降低同型半胱氨酸水平可以预防及改善认知功能。

未来需要更多大规模临床试验进一步的研究论证。

【关键词】高同型半胱氨酸血症认知功能障碍 MTHFR突变基因叶酸 B族维生素同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,Hcy)是人体内的重要的代谢指标,是氨基酸分解过程中的重要中间产物,由甲硫氨酸、半胱氨酸分解过程中产生。

一般情况下,同型半胱氨酸可通过分解代谢,在体内维持较低水平。

当各种原因引起体内同型半胱氨酸代谢失衡,体内血浆总同型半胱氨酸值>15umol/L时可诊断为高同型半胱氨酸血症(HHcy)。

高同型半胱氨酸血症会增加认知功能障碍发生的风险[1]。

目前同型半胱氨酸对认知功能障碍的作用机制尚不明确。

本文对同型半胱氨酸的体内代谢机制及其影响因素、高同型半胱氨酸血症对认知功能障碍的作用等方面的研究进展进行综述,并探讨高同型半胱氨酸血症的治疗对认知功能障碍的影响。

1.Hcy代谢机制及影响因素同型半胱氨酸体内代谢主要有两条途径:转硫作用和再甲基化[2],如图1。

同型半胱氨酸由胱硫醚-β-合成酶催化通过转硫作用生成半胱氨酸,其过程中需要磷酸吡哆醛(维生素B6)作为辅因子[3]。

所以当体内维生素缺乏,特别是叶酸、维生素B12、维生素B6缺乏可能会引起同型半胱氨酸升高[3]。

而同型半胱氨酸另一代谢途径再甲基化通常发生在人类心脏、肝脏和肾脏中,Hcy是由甲硫氨酸合成酶或甜菜碱-同型半胱氨酸甲基转移酶催化产生甲硫氨酸[4]。

老年人临床营养管理进展答案-华医网2025年度项目继续教育

老年人临床营养管理进展华医网2025年度项目答案科目:一、消化系统衰老与营养【上】 (1)二、消化系统衰老与营养【下】 (2)三、老年人蛋白质-能量营养不良 (3)四、老年临床营养管理指导原则 (4)五、老年肌少症的营养管理 (5)六、老年慢病的营养管理 (5)七、老年卒中全程营养管理的进展与思考 (6)八、老年共病状态下的营养管理 (7)九、老年人营养不良干预实操 (8)十、老年营养风险筛查 (9)十一、《中国老年重症患者肠内营养支持专家共识》解读 (10)十二、老年人的生理特点与营养需求 (11)一、消化系统衰老与营养【上】1.人体必需得七大营养素是()正确答案:A、水、蛋白质、脂类、碳水化合物、膳食纤维、维生素、矿物质2.胃酸的功能有()正确答案:E、前面4个选项都是3.以下哪项描述不是老年人吞咽功能下降导致的结果?正确答案:B、老年人咽—UES(上食管括约肌)收缩反射和咽反射的容量阈值升高,使得食物更容易通过咽部正确答案:上食管括约肌4.营养物质吸收的主要场所是()正确答案:B、小肠5.以下哪项不是老年人胃电及胃动力异常对营养摄取和消化产生的可能影响?正确答案:C、老年人胃中间横带的出现,可能导致胃内食物分布均匀,有利于食物的消化和吸收二、消化系统衰老与营养【下】1.以下关于肝脏衰老的描述中不正确的是()正确答案:C、肝脏衰老后,其有效血流量会增加以维持正常功能2.老年人营养不良发生三要素是()正确答案:E、A、B、C都是3.肠道微生态老化的特点有()正确答案:E、前面四个选项都是4.肠道菌群可以参与合成哪种维生素?()正确答案:A、维生素K5.以下是具有抗炎作用菌群的是()正确答案:D、乳酸杆菌三、老年人蛋白质-能量营养不良1.老年人PEM占老年人营养不良的()正确答案:A、35%2.以下哪一项描述最不符合“营养不良”的定义?()正确答案:D、短期内因食物中毒导致的体重减轻和身体不适3.老年人发生PEM的要素有()正确答案:E、A、B、C都是4.医院ICU老年人PEM患病率高达()正确答案:C、50%5.以下哪项措施是确保老年人营养素摄入充足的有效方法正确答案:B、针对老年人口咽功能退化,为老年人制做细软可口、营养丰富的食物四、老年临床营养管理指导原则1.老年人营养不良的后果有()正确答案:E、A、B、C、D都是2.膳食纤维,推荐每日摄入量为()正确答案:C、25-30g/d3.以下哪种指征的患者应接受营养干预()正确答案:A、经口摄入不足目标量80%4.老年人的营养评估指标有()正确答案:E、A、B、C、D都是5.关于误吸预防和处理,以下哪项措施是不正确的?正确答案:C、成人管饲时,无论患者情况如何,都应选择14号胃管五、老年肌少症的营养管理1.相关研究显示,ONS可显著降低营养不良老年住院患者的出院后()天死亡率正确答案:A、90天2.以下不属于导致继发性肌少症产生因素的是()正确答案:C、增龄3.2022年发表的Meta分析结果显示全球肌少症总体患病率()正确答案:A、10-27%4.研究显示,老年肌少症患者骨折风险增加近()正确答案:E、2倍5.根据2020年人口普查数据,中国老年占全国人数的()正确答案:B、18.7%六、老年慢病的营养管理1.2023年发表的《中国心血管健康与疾病报告2022》:()是中国居民疾病死亡首要原因正确答案:A、心血管病2.2020年发表的《中国居民营养与慢性病状况报告》数据显示,中国因慢病导致的死亡占总死亡的()正确答案:C、88.5%3.2019年我国因慢性病导致的死亡占总死亡(),其中心脑血管病、等慢性病死亡比例为()正确答案:A、88.5%,80.7%4.2024年发表的ESPEN《多发病住院患者的营养支持实践指南》推荐:老年多发病住院患者,出院后继续营养支持(ONS)至少几个月()正确答案:B、2个月5.对2022年发表的系统综述和荟萃分析结果描述正确的是()正确答案:D、A、B、C都正确七、老年卒中全程营养管理的进展与思考1.以下哪一项不是2021ASA/AHA指南中推荐的DASH饮食模式强调的食物类别()正确答案:C、高脂肪乳制品2.关于卒中可干预的危险因素有()正确答案:E、前面四个选项都是3.以下哪项关于脑血管病的描述是正确的?()正确答案:E、脑血管病是世界范围内成人致残、致死的主要原因之一4.关于中国脑血管病的情况,以下哪项描述是正确的?()正确答案:C、中国脑血管病的死亡率是欧美国家的5倍5.关于DASH饮食模式与心脑血管病风险的关系,以下哪个说法不正确?()正确答案:D、2021ASA/AHA指南不推荐DASH饮食模式来降低心脑血管病风险八、老年共病状态下的营养管理1.2021年发表的中国研究Meta分析结果:1/3中国中老年居民慢病共病患病率:()正确答案:D、41%2.2022年发表的纳入193项国际研究的系统综述和荟萃分析结果:全球多发病合并患病率高达正确答案:C、42.4%3.脑卒中发病后()小时内早期开始营养支持治疗正确答案:B、24-48小时4.多发病的病理生理与机制有()正确答案:E、前面4个现象都是5.老年糖尿病营养不良,肾脏功能正常的患者,蛋白质摄入量应为()正确答案:C、1.0-1.5g/kg/d九、老年人营养不良干预实操1.关于ONS口服营养补充剂治疗者的随访频率,下列哪项描述是正确的?正确答案:C、社区或出院患者的随访频率应至少为每周两次2.2018年发表的以色列研究结果:_x000b_医生处方,可提高老年患者出院后ONS依从性近()倍正确答案:A、5倍3.ONS依从性的影响因素有()正确答案:E、前面4个选项都是4.出现ONS不耐受的处理措施是()正确答案:E、A、D都是5.2016年发表的美国临床研究结果:ONS显著降低营养不良老年住院患者的()死亡率正确答案:D、90天十、老年营养风险筛查1.以下关于老年患者营养不良的随访计划不正确的是()正确答案:C、干预结束后每两个月随访1次2.营养不良对老年患者可能产生哪些不良影响()正确答案:D、增加老年患者的住院天数和住院费用3.营养不良对老年人健康的潜在影响有哪些?()正确答案:E、前面4个选项都是4.可在社区应用的筛查评估工具是()正确答案:A、MNA-SF5.2022年发表的Meta分析结果:中国社区老年人营养不良或营养风险合并患病率是()正确答案:A、41.2%十一、《中国老年重症患者肠内营养支持专家共识》解读1.住院老年吞咽障碍患者营养不良的发生率高达(),故此类患者在经口进食前需进行吞咽功能筛查正确答案:A、37%-67%2.指南建议老年患者进行持续鼻饲喂养时,床头抬高()正确答案:C、30°-45°3.一项中国研究结果,中国重症患者存在营养不良风险的比率高达()正确答案:B、97.22%4.老年休克患者出现以下哪种情况时应采用延迟肠内营养()正确答案:D、A、B、C5.根据指南推荐,老年患者需要的目标喂养热量是()正确答案:A、25-30kcal•kg-1•d-1十二、老年人的生理特点与营养需求1.老年人营养干预的治疗目标是()正确答案:A、≥70%的能量目标需求90%的液体目标需求100%的蛋白质目标需求100%的微)2.2020年第七次全国人口普查主要数据:中国≥60岁老年人占()正确答案:E、18.7%3.为什么建议老年人增加膳食蛋白质的摄入量?正确答案:D、老年人利用现有蛋白质的能力下降,且蛋白质需求量增加,同时正常蛋白质摄入量可能减少4.2022年发表的中国临床研究结果显示隐性饥饿的社区老年人补充ONS()个月,显著升高白蛋白水平正确答案:A、3个月5.2022年发表的Meta分析结果显示老年人牙齿缺失,营养不良或营养不良风险增加()正确答案:C、21%。

系统综述解读

系统综述与传统综述的区别

传统综述

系统综述

问题

涉及面常较广

常集中于某一临床问题

文献来源和收集 不系统、全面,可能存在 收集全面,有规定的步

偏倚

骤和策略

筛选文献

没有统一标准,常存在偏 根据统一标准筛选文献

倚

质量评价

常无或随意性大

强有力的评价标准

资料综合

常常为定性描述

定量综合,如 meta-分析

推论(结论)

请大家计算OR, RR!

Tanzania 1995

治疗组

妊娠诱发 高血压

2

没有诱发 高血压

62

对照组

4

59

合计

9

121

合计

64 63 127

计算:治疗对妊娠诱发高血压发生机会影响的危险率 (RR);

治疗对妊娠诱发高血压发生机会影响的比值比(OR).

答案

Tanzania 1995

治疗组

妊娠诱发 高血压

odds = 发生某一事件的人数 未发生某事件的人数

组间比较——2x2表

Blum et al 患有消化

不良

治疗组

119

没有消化 不良

45

对照组

130

34

合计

249

79

合计

164 164 328

Blum et al 患有消化 没有消化 合 计

危险度与比值的比较 不良

不良

治疗组

119

45

164

对照组

130

odds = 4/59=0.068

危险比率(risk ratio, RR)=பைடு நூலகம்对危险度(relative risk, RR)

荟萃分析

平均绝经年龄 标准差 43.43 3.11 吸烟 45.59 4.73 不吸烟

样本量 40 242

10

荟萃分析数据处理基本步骤 1.效应量的选择和各独立研究的效应量大小的 计算; 2.异质性检测;

3.计算平均效应量;

4. 偏倚检测。

11

1.效应量的选择和各独立研究的效应大小的计算 1)效应量的选择 效应量(effect size / ES):定量测量一种 因素与另一因素之间关联强度的统计量。 ① 二分类变量:比值比( OR ),绝对危险度 (AR);相对危险度(RR);风险差(RD)等。 ② 连续变量:加权均差(WMD);标准化均差 (SMD);Hedges’g等。

21

异质性检的测结果和处理方法。

1)若异质性不明显,则选择固定效应模型来 合并效应值。

2)若异质性明显,则应选择随机效应模型来 合并效应值,并且通常需要进一步同过亚组分析和 荟萃回归分析来探讨异质性的来源。

3)当异质性过于明显且不能排除,也不能弄 清楚来源时,则应放弃荟萃分析,只做一般的定性 描述 。

4 .文献数据提取 根据我们研究需要,提取文献的各种数据如: 研究特征,测量结果等。提取过程确保数据的正确 性。

6

5 .统计学分析 将提取的相关数据进行统计学处理和综合分析 (本次课重点内容,后面详细介绍)。

6 .结论和讨论 结合分析的结果和相关专业知识做出结论,并 对本次研究的过程和结果展开讨论。

二分类为两种相互排斥相互对立的事物,如: 早绝经与晚绝经。 举例,吸烟对绝经关系的二分类数据(规定绝 经年龄大于50岁晚绝经,小于50岁为早绝经) 晚绝经 262 211 早绝经 168 108

9

吸烟 不吸烟

连续变量数据

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

ReviewCoping strategies and psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia:A systematic review and meta-analysisRyan Li ⁎,Claudia Cooper,Jonathan Bradley,Amanda Shulman,Gill LivingstonDepartment of Mental Health Sciences,University College London,Holborn Union Building,Highgate Hill,London N195LW,United Kingdoma r t i c l e i n f o ab s t r ac tArticle history:Received 1March 2011Received in revised form 27May 2011Accepted 27May 2011Available online 2July 2011Background :Carers for people with dementia experience high levels of anxiety and depression.Coping style has been associated with carer anxiety and depression.Method :We systematically reviewed studies examining the relationships between coping and anxiety or depression among carers of people with dementia.We rated study validity using standardised checklists.We calculated weighted mean correlations (WMC)for the relation-ships between coping and psychological morbidity,using random effects meta-analyses.Results :We included 35studies.Dysfunctional coping correlated with higher levels of anxiety (WMC =0.39,95%CI 0.28–0.50;N =688)and depression (0.46,0.36–0.56;N =1428)cross-sectionally,and with depression 6and 12months later (0.32,0.10–0.54;N=143).Emotional support and acceptance-based coping correlated with less anxiety (−0.22,95%CI −0.26to −0.18;N =628)and depression (−0.20,−0.28to −0.11;N=848)cross-sectionally;and predicted anxiety and depression a year later in the only study to measure this.Solution-focused coping did not correlate signi ficantly with psychological morbidity.Limitations :Just over a quarter of the identified studies provided extractable data for meta-analysis,including only two longitudinal studies.Conclusions :There is good evidence that using more dysfunctional,and less emotional support and acceptance-based coping styles are associated with more anxiety and depression cross-sectionally,and there is preliminary evidence from longitudinal studies that they predict this morbidity.Our findings would support the development of psychological interventions for carers that aim to modify coping style.©2011Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.Keywords:Dementia Carers CopingSystematic review Meta-analysisContents 1.Introduction .......................................................22.Methods .........................................................22.1.Search strategy ...................................................22.2.Inclusion and exclusion criteria ...........................................22.3.Categorising coping ................................................22.4.Quality assessment .................................................22.5.Data extraction ...................................................32.6.Analysis ......................................................33.Results ..........................................................33.1.Study description and methods ...........................................33.2.Cross-sectional studies ...............................................3Journal of Affective Disorders 139(2012)1–11⁎Corresponding author.Tel.:+442072883559;fax:+442072883411.E-mail address:ryan.li@ (R.Li).0165-0327/$–see front matter ©2011Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.055Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of Affective Disordersj o u r n a l h om e p a g e :w w w.e l s ev i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /j a d3.2.1.Anxiety (7)3.2.2.Depression (7)3.2.3.Mixed psychological morbidity (7)3.3.Longitudinal studies (7)3.3.1.Anxiety (8)3.3.2.Depression (9)4.Discussion (9)4.1.Limitations (10)4.2.Clinical implications (10)Role of funding source (10)Conflict of interest (10)Acknowledgements (10)References (10)1.IntroductionFamily carers of people with dementia have high levels of anxiety and depression(Cooper et al.,2007;Crespo et al., 2005;Pinquart and Sorensen,2003).This psychological morbidity has been found to be most strongly associated with the coping strategies used by the carer,as well as demographic characteristics of the carer and neuropsychiatric symptoms and illness severity in the person with dementia (Cooper et al.,2008).Nonetheless earlier studies have reported conflicting results about the relationships between emotion-focused or dysfunctional coping styles and psycho-logical morbidity(Crespo et al.,2005;Neundorfer,1991; Proctor et al.,2002;Shaw et al.,1997;Vedhara et al.,2001).Coping is the process by which people manage stress.If coping strategies are important contributors to carer psycho-logical morbidity,then understanding which styles are protective and which are detrimental may inform the development of interventions.Coping strategies were initially divided into emotion-focused and problem-focused(Lazarus and Folkman,1984).Later a third category of dysfunctional coping was suggested(Carver et al.,1989).Kneebone and Martin(2003)reviewed12cross-sectional and6longitudinal studies,and concluded that problem-solving and acceptance styles of coping appear to be advantageous for carers of people with dementia,but commented their findings were limited because studies failed to identify the influence of the stressors.Greater stressors would be expected to elicit more coping strategies as well as increasing anxiety and depression.We aimed to systematically review and meta-analyse the relationships between coping strategies and psychological morbidity in family carers for people with dementia.We examined the measures of coping and re-classified them to ensure comparability between studies.We also took into account two specific stressors,the severity of dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms of the care recipient,as the use of coping strategies is expected to increase as stressors increase.2.Methods2.1.Search strategyWe searched EMBASE,MEDLINE,PsycINFO,Web of Science,CINAHL and AMED up to March2010.The search terms were:(carer OR caregiver OR caring OR relative OR supporter OR family);(dementia OR Alzheimer OR cognitive impairment);coping;(anxiety OR depression OR mood OR psychiatric morbidity OR psychological morbidity).We hand-searched relevant reviews and the references of included studies.We also asked authors of all the included studies whether they were aware of any further studies.2.2.Inclusion and exclusion criteriaWe included primary research studies,published in English that reported the relationship(for example as correlations or regression analyses)between coping strate-gies and psychological morbidity in family/informal carers of people with any form of dementia.Studies that reported data on carers of people without dementia were excluded,unless they reported the results for dementia carers separately.We included only studies that used standardised,quantitative measures of coping and psychological morbidity,and only where the coping measure could be classified according to our categorisation described as follows.2.3.Categorising copingWe categorised coping strategies as solution-focused, emotional support and acceptance-based,or dysfunctional, using Carver's(1997)definitions of problem-focused,emo-tion-focused and dysfunctional coping as a framework.The three categories have demonstrated satisfactory psychomet-ric properties for carers of people with dementia(Cooper et al.,2008).For every coping scale used in the included studies,RL classified its respective subscales into the three categories by examining the individual questions.This classification was then discussed with and agreed with two other authors(GL and CC)(see Table1).2.4.Quality assessmentRL and one other author(AS or JB)independently rated the quality of each study,blind to each other's ratings.Disagree-ments were resolved through discussion with GL.Our measure of study validity was adapted from Boyle(1998).For cross-sectional studies,we awarded points as follows:•Power analysis based on relationship between coping and depression/anxiety:1point2R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders139(2012)1–11•Clearly defined population:1point •Representative sample:1point for probability sampling,or whole population was recruited(for example,consecutive sampling).•Participants and non-participants comparable:1point if demonstrated statistically,or if participation rate≥80%•Reliability and validity:for each,0.5point if measures of psychological morbidity and coping validated in target population,0.25points if validated only in another population.•Confounding factors:1point if all of the following confounders were identified or addressed;carer gender and physical health,care recipient neuropsychiatric symp-toms,carer burden.For longitudinal studies,we applied two additional criteria:1point if participants were followed up for at least 6months;1point if at least80%of participants were followed up(or those lost to follow-up were shown to be comparable). We classified studies with a quality score of3or greater as higher quality studies.2.5.Data extractionFor each study,we extracted any correlation or regression coefficients reported for the relationship between a coping subscale and psychological morbidity.We tabulated the direction and statistical significance of the relationship under the three broad categories of coping(Tables2and3). We excluded correlation or regression coefficients reported for individual questions,or for any coping measures that could not be categorised using our system.2.6.AnalysisWe conducted meta-analyses by extracting the standardised beta regression coefficients from studies for the relationships between depression,anxiety or mixed psychological morbidity and the categories of coping strategy.We calculated relevant regression coefficients from our own unpublished data(Cooper et al.,2008,2010).Coefficients were pooled to produce a weighted mean correlation(WMC)coefficient,using a random effects model to account for heterogeneity(Hunter and Schmidt, 1990).Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS17 software package(SPSS Inc.,2008).We used StatsDirect2.6.6to produce forest plots of the results(StatsDirect Ltd.,2008).As dementia severity was a known confounder in the relationship between carer coping and mental health,we included in our meta-analysis only studies that controlled for severity of dementia(either by cognitive status or duration of illness)or neuropsychiatric symptoms.3.Results3.1.Study description and methodsFrom5396publications identified by our systematic searches,we included35unique studies(28cross-sectional and seven longitudinal)reported across37 publications.One paper(Shaw et al.,1997)reported different study procedures for its US and China samples; we have included these two different studies as two separate studies(Fig.1).Most(30)of the studies were from developed,English-speaking countries;of the remainder,two were from Taiwan (Fuh et al.,1999;Huang et al.,2006),and there was one each from Belgium(Schoenmakers et al.,2009),the Netherlands (Pot et al.,2000)and China(Shaw et al.,1997).3.2.Cross-sectional studiesTable2summarises characteristics,results and the quality of the included cross-sectional studies.Four longitudinal studies additionally provided cross-sectional baseline data (Cooper et al.,2006;Kinney et al.,2003;Matson,1994; Vedhara et al.,2000.Table3).Dysfunctional coping was most often reported to be positively associated with anxiety,while most papers considering emotional support and acceptance-based coping or solution-focused coping reported non-significant associations with anxiety.For depression,a large majority of papers reported positive association with dys-functional coping;emotional support and acceptance-based coping and solution-focused coping and was most often reported with non-significant or negative associations. Overall,there was no observable difference in the direction and statistical significance offindings between higher and lower quality studies.We extracted and meta-analysed regression coefficients from the11studies that controlled for severity of dementia or neuropsychiatric symptoms.All of these studies measured either depression or anxiety,except for the single study providing extractable data on mixed psychological morbidity (Hinrichsen and Niederehe,1994).Table1Classification of coping strategies.Selection of coping subscales/factors[exemplar items in brackets]and source coping measure,categorised by RL. Solution-focused Emotional support and acceptance-based DysfunctionalActive coping[I've been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I'm in]Brief COPEPlanful problem-solving[I knew what had to be done,so I doubled my efforts to make things work] Ways of Coping QuestionnaireLogical analysis[Considered several alternatives for handling the problem]Coping Responses Inventory Active behavioural[Made a plan of action and followed it]Health and Daily Living Form Using emotional support[I've been gettingemotional support from others]Brief COPEPositive reappraisal[Changed or grew as aperson in a good way]Ways of CopingQuestionnaireAffective regulation[Tried to see the positiveside of the situation]Coping ResponsesInventoryActive cognitive[Prayed for guidance and/orstrength]Health and Daily Living FormDenial[I've been saying to myself“This isn't real”]Brief COPEAccepting responsibility[Criticized or lecturedmyself]Ways of Coping QuestionnaireAvoidance[Avoided being with people in general]Health and Daily Living FormEmotional discharge[Let my feelings out somehow]3R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders139(2012)1–113.2.1.AnxietyEmotional support and acceptance-based coping was associated with less anxiety (WMC =−0.220,95%CI −0.259to −0.180;p b 0.0005;3studies;N=628).Dysfunc-tional coping was associated with more anxiety (WMC=0.390,95%CI 0.283to 0.498;p b 0.0005;4studies;N=688),while solution-focused coping was not signi ficantly associated with anxiety (WMC=0.096,95%CI −0.020–0.212;p=0.104;4studies;N=678)(Fig.2).3.2.2.DepressionEmotional support and acceptance-based coping was associated with less depression (WMC=−0.196,95%CI −0.283to −0.109;p b 0.0005;5studies;N=848).Dysfunc-tional coping was associated with more depression (WMC=0.456,95%CI 0.357to 0.555;p b 0.0005;10studies;N=1428),while solution-focused coping was not signi fi-cantly associated with depression (WMC=−0.035,95%CI −0.113to 0.043;p=0.376;4studies;N=700)(Fig.3).3.2.3.Mixed psychological morbidityOnly one study provided extractable data on mixed psycho-logical morbidity (Hinrichsen and Niederehe,1994).This found dysfunctional coping to be associated with more distress (standardised beta=0.350,p b 0.001,N=152),but no signi fi-cant association between solution-focused coping and distress (standardised beta=0.090,not signi ficant,N=152).It did not examine emotional support and acceptance-based coping.3.3.Longitudinal studiesTable 3summarises characteristics,results and the quality of the included longitudinal studies,two of which provided5396 hits(5392 electronic search, 4 hand-search)607 potential references:abstracts retrieved192 full texts retrieved35 studies included in review (published across 37 papers)11 studies with regression analysescontrolling for confounders:included in meta-analysisExcluded: 126 no measures of relationship betweencoping and anxiety/depression16 no specific data on carers of people with dementia13 intervention studiesExcluded: 305 did not report all required outcomemeasures77 not primary quantitative study33 no specific data on carers of people with dementiaExcluded by title:4342 clearly irrelevant 38 not peer-reviewed journal409 duplicatesFig.1.Flowchart of included/excluded studies.7R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders 139(2012)1–11extractable data for meta-analysis (Cooper et al.,2008;Vedhara et al.,2000).3.3.1.AnxietyEmotional support and acceptance-based coping was associated with less anxiety (standardised beta =−0.195,p =0.020)and solution-focused coping with greater anxiety a year later (standardised beta =0.299,p =0.002)in the only included study (n =93)to measure these types of coping (Cooper et al.,2008).Dysfunctional coping at baseline did not signi ficantly predict anxiety 6months (Vedhara et al.,2000)or 12months later (WMC =0.190,95%CI −0.158to 0.539;Cooper et al.,2008)(p =0.284;2studies;N =143).0.39 (0.28, 0.50)Cooper et al. 20010.56 (0.40, 0.68)Cooper et al. 20060.44 (0.32, 0.54)Neundorfer 19910.53 (0.32, 0.69)0.28 (0.17, 0.38)Cooper et al. 20100.10 (-0.02, 0.21)Cooper et al. 20100.12 (-0.01, 0.25)Cooper et al. 20060.23 (0.04, 0.41)Proctor et al. 2002-0.01 (-0.12, 0.10)0.38 (0.11, 0.60)Cooper et al. 20060.29 (-0.46, -0.10)abcFig.2.Forest plots showing standardised regression coef ficients between coping styles and anxiety,and their weighted mean correlations (random effects models),after controlling for neuropsychiatric symptoms and dementia severity.Parentheses indicate 95%con fidence intervals.Studies in bold are higher quality.a:Relationship between solution-focused coping and anxiety b:Relationship between emotional support and acceptance-based coping and anxiety c:Relationship between dysfunctional coping and anxiety.8R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders 139(2012)1–113.3.2.DepressionDysfunctional coping signi ficantly predicted depression at follow-up (WMC=0.321,95%CI 0.098to 0.544;p=0.005;2studies;N=143).Neither emotional support nor acceptance-based coping (standardised beta=−0.149,p=0.28)nor solution-focused coping (standardised beta=0.112,p=0.46)signi ficantly predicted depression a year later (n=93;Cooper et al.,2008).4.DiscussionThis is the first meta-analysis of the relationships between carer coping and psychological morbidity and the first systematic review to take into account the effect of stressors.We found consistent evidence from higher quality cross-sectional studies that dysfunctional coping was moderately correlated (WMC ≈0.4)with depression and anxiety.There was also evidence from two high quality longitudinal studies that dysfunctional coping predicted depression 6and 12months later.Coping strategies based on acceptance and seeking emotional support were correlated cross-sectionally to a lesser degree (WMC ≈0.2)with lower anxiety and depression in high quality studies.In one study these coping strategies predicted lower anxiety and depression a year later (Cooper et al.,2008).Our meta-analysis suggests that solution-focused coping is not cross-sectionally associated with carer mental health,which challenges the typical assumption in the literature thatCooper et al. 2010Kim et al. 2007Huang et al. 2006Cooper et al. 2006Haley et al. 1996Kramer 1993Neundorfer 1991Cooper et al. 2010Huang et al. 2006Cooper et al. 2006Kramer 1993Cooper et al. 2010Cooper et al. 2006Kramer 1993abcFig.3.Forest plots showing standardised regression coef ficients between coping styles and depression,and their weighted mean correlations (random effects models),after controlling for neuropsychiatric symptoms and dementia severity.Parentheses indicate 95%con fidence intervals.Studies in bold are higher quality.a:Relationship between solution-focused coping and depression b:Relationship between emotional support and acceptance-based coping and depression c:Relationship between dysfunctional coping and depression.9R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders 139(2012)1–11solution-focused coping has positive implications for carer mental health(for example,see Kneebone and Martin,2003). The only study that explored such a relationship longitudinally found that carers who reported using more solution-focused coping strategies relative to other forms of coping at baseline, tended to show more symptoms of anxiety and depression at 12months follow-up(Cooper et al.,2008).This might be explained by the inevitability of dementia as a progressive and incurable illness,in which stressors associated with the illness become less amenable to problem-solving over time(Cooper et al.,2008).This is not to suggest solution-focused behaviours have no benefits at all;our review did not consider any outcomes other than carer psychological morbidity.Studies that have investigated coping have tended to use a wide variety of coping measures(Kneebone and Martin, 2003).This is thefirst review to synthesise studies of carer coping in dementia using a common classification system for different coping measures,enabling meaningful comparisons of results obtained with different measures.4.1.LimitationsWe could only include just over a quarter of the identified studies in our meta-analysis;the remainder of studies did not control for relevant stressors.There was a particular dearth of longitudinal studies,and only two included data that we could extract for analysis.A number of coping subscales could not be extracted from otherwise relevant studies,because the coping subscales did notfit into one of our three pre-defined categories,but we have no reason to think that this introduces a particular bias to ourfindings.4.2.Clinical implicationsDysfunctional coping behaviours are performed by every-one to some degree(as are all coping behaviours).Coping scales are not all-or-nothing but instead measure how much of a coping style is used,and what implications this has for carer mental health.Our meta-analysis provides good evidence that the greater use of dysfunctional coping and less use of coping based on acceptance and support are associated with anxiety and depression cross-sectionally;there is preliminary evi-dence(from one or two studies)that they also predict this morbidity from longitudinal studies.This suggests that psychological interventions aimed at modifying coping style carers use would be rational interventions.We are currently recruiting participants for such a trial.Role of funding sourceThis study was completed by the authors in their capacities as employees of UCL.UCL had no further role in the study design;in the collection,analysis and interpretation of data;in the writing of the report;and in the decision to submit this paper for publication.Conflict of interestCC and GL authored some of the papers in this review.All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank all authors who responded to our request for publications.ReferencesAshley,N.R.,Kleinpeter,C.H.,2002.Gender differences in coping strategies of spousal dementia caregivers.J.Hum.Behav.Soc.Env.6,29–46.Batt-Leiba,M.I.,Hills,G.A.,Johnson,P.M.,Bloch,E.,1998.Implications of coping strategies for spousal caregivers of elders with dementia.Top.Geriatr.Rehabil.14,54–62.Boyle,M.H.,1998.Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies.Evid.Based Ment.Health.1,37–39.Brashares,H.J.,Catanzaro,S.J.,1994.Mood regulation expectancies,coping responses,depression,and sense of burden in female caregivers of Alzheimer's patients.J.Nerv.Ment.Dis.182,437–442.Carver,C.S.,1997.You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE.Int.J.Behav.Med.4,92–100.Carver,C.S.,Scheier,M.F.,Weintraub,J.K.,1989.Assessing coping strategies:a theoretically based approach.J.Pers.Soc.Psychol.56,267–283. Cooper,C.,Balamurali,T.B.,Livingston,G.,2007.A systematic review of the prevalence and covariates of anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia.Int.Psychogeriatr.19,175–195.Cooper,C.,Katona,C.,Orrell,M.,Livingston,G.,2006.Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease:the LASER-AD study.J.Affect.Disord.90,15–20.Cooper,C.,Katona,C.,Orrell,M.,Livingston,G.,2008.Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease.Int.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry.23,929–936.Cooper,C.,Selwood,A.,Blanchard,M.,Walker,Z.,Blizard,R.,Livingston,G., 2010.The determinants of family carers'abusive behaviour to people with dementia:results of the CARD study.J.Affect.Disord.121,136–142. Crespo,M.,Lopez,J.,Zarit,S.H.,2005.Depression and anxiety in primary caregivers:a comparative study of caregivers of demented and nondemented older persons.Int.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry.20,591–592. Fuh,J.-L.,Wang,S.-J.,Liu,H.-C.,Liu,C.-Y.,Wang,H.-C.,1999.Predictors of depression among Chinese family caregivers of Alzheimer patients".Alzheimer Dis.Assoc.Disord.3,171–175.Goode,K.T.,Haley,W.E.,Roth,D.L.,Ford,G.R.,1998.Predicting longitudinal changes in caregiver physical and mental health:a stress process model.Health Psychol.17(2),190–198.Haley,W.E.,Levine,E.G.,Brown,S.L.,Bartolucci,A.A.,1987.Stress,appraisal, coping,and social support as predictors of adaptational outcome among dementia caregivers.Psychol.Aging2,323–330.Haley,W.E.,Roth,D.L.,Coleton,M.I.,Ford,G.R.,West,C.A.,Collins,R.P.,Isobe, T.L.,1996.Appraisal,coping,and social support as mediators of well-being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease.J.Consult.Clin.Psychol.64,121–129.Hinrichsen,G.A.,Niederehe,G.,1994.Dementia management strategies and adjustment of family members of older patients.Gerontologist34, 95–102.Huang,C.,Musil,C.M.,Zauszniewski,J.A.,Wykle,M.L.,2006.Effects of social support and coping of family caregivers of older adults with dementia in Taiwan.Int.J.Aging Hum.Dev.63,1–25.Hunter,J.E.,Schmidt,F.L.,1990.Methods of Meta-analysis:Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings.Sage,Newbury Park,CA.Kim,J.-H.,Knight,B.G.,Longmire,C.V.F.,2007.The role of familism in stress and coping processes among African American and white dementia caregivers:effects on mental and physical health".Health Psychol.26, 564–576.Kinney,J.M.,Ishler,K.J.,Pargament,K.I.,Cavanaugh,J.C.,2003.Coping with the uncontrollable:the use of general and religious coping by caregivers to spouses with dementia.J.Relig.Gerontol.14,171–188.Knight,B.G.,Silverstein,M.,McCallum,T.J.,Fox,L.S.,2000.A sociocultural stress and coping model for mental health outcomes among African American caregivers in southern California.J.Gerontol.B.Psychol.Sci.Soc.Sci.55B,142–150.Knop,D.S.,Bergman-Evans,B.,McCable,B.W.,1998.In sickness and in health: an exploration of the perceived quality of the marital relationship, coping,and depression in caregivers of spouses with Alzhemier's disease.J.Psychosoc.Nur.Ment.Health Serv.36,16.Kneebone,I.I.,Martin,P.R.,2003.Coping and caregivers of people with dementia.Br.J.Health Psychol.8,1–17.Kramer,B.J.,1993.Expanding the conceptualization of caregiver coping:the importance of relationship-focused coping strategies.Fam.Relat.42, 383–391.Lazarus,R.S.,Folkman,S.,1984.Stress.Appraisal and Coping,Springer,NY. Livingston,G.,Regan, C.,Cooper, C.,Orrell,M.,Katona, C.,2007.Mood disorders in people with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers:the LASER-AD study.Int.J.Psychiatry Clin.Prac.11(Suppl.1),12. Lutzky,S.M.,Knight,B.G.,1994.Explaining gender differences in caregiver distress:the roles of emotional attentiveness and coping styles.Psychol.Aging9,513–519.10R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders139(2012)1–11Matson,N.,1994.Coping,caring and stress:a study of stroke carers and carers of older confused people.Br.J.Clin.Psychol.33,333–344. Morano,C.L.,2003.Appraisal and coping:moderators or mediators of stress in Alzheimer's disease caregivers?Soc.Work.Res.27,116–128. Mausbach,B.T.,Aschbacher,K.,Patterson,T.L.,Ancoli-Israel,S.,von Kanel,R., Mills,P.J.,Dimsdale,J.E.,Grant,I.,2006.Avoidant coping partially mediates the relationship between patient problem behaviors and depressive symptoms in spousal Alzheimer caregivers.Am.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry.14,299–306.Neundorfer,M.M.,1991.Coping and health outcomes in spouse caregivers of persons with dementia.Nurs.Res.40,260–265.Parks,S.H.,Pilisuk,M.,1991.Caregiver burden:gender and the psychological costs of caregiving.Am.J.Orthopsychiatry.61,501–509.Pinquart,M.,Sorensen,S.,2003.Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health:a meta-analysis.Psychol.Aging18,250–267.Pot,A.M.,Deeg,D.J.,van Dyck,R.,2000.Psychological distress of caregivers: moderator effects of caregiver resources?Patient Educ Couns.41, 235–240.Powers, D.V.,Gallagher-Thompson, D.,Kraemer,H.C.,2002.Coping and depression in Alzheimer's caregivers:longitudinal evidence of stability.J.Gerontol.B Psychol.Sci.Soc.Sci.57B,205–211.Proctor,R.,Martin, C.,Hewison,J.,2002.When a little knowledge is a dangerous thing…:a study of carers'knowledge about dementia, preferred coping style and psychological distress.Int.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry.17,1133–1139.Pruchno,R.A.,Resch,N.L.,1989.Mental health of caregiving spouses:coping as mediator,moderator,or main effect?Psychol.Aging4,454–463. Saad,K.,Hartman,J.,Ballard,C.,Kurian,M.,Graham,C.,Wilcock,G.,1995.Coping by the carers of dementia sufferers.Age Ageing24,495–498. Schoenmakers,B.,Buntinx,F.,De Lepeleire,J.,2009.The relation between care giving and the mental health of caregivers of demented relatives:a cross-sectional study.Eur.J.Gen.Pract.15,99–106.Shaw,W.S.,Patterson,T.L.,Semple,S.J.,Grant,I.,Yu,E.S.,Zhang,M.,He,Y.Y., Wu,W.Y.,1997.A cross-cultural validation of coping strategies and their associations with caregiving distress.Gerontologist37,490–504. SPSS Inc.,2008.SPSS for Windows,Rel.17.0.0.SPSS Inc.,Chicago. StatsDirect Ltd.,2008.StatsDirect version2.6.6.Stats Direct Ltd.,Chesire. Vedhara,K.,Shanks,N.,Anderson,S.,Lightman,S.,2000.The role of stressors and psychosocial variables in the stress process:a study of chronic caregiver stress.Psychosom.Med.62,374–385.Vedhara,K.,Shanks,N.,Wilcock,G.,Lightman,S.L.,2001.Correlates and predictors of self-reported psychological and physical morbidity in chronic caregiver stress.J.Health Psychol.6,101–119.Vitaliano,P.P.,Maiuro,R.D.,Russo,J.,Becker,J.,1987.Raw versus relative scores in the assessment of coping strategies.J.Behav.Med.10,1–18. Wilcox,S.,O'Sullivan,P.,King,A.C.,2001.Caregiver coping strategies:wives versus daughters.Clin.Gerontol.23,81–97.Williamson,G.M.,Schulz,R.,1993.Coping with specific stressors in Alzheimer's disease caregiving.Gerontologist37,747–755.Wright,L.K.,1994.AD spousal caregivers:longitudinal changes in health, depression,and coping.J.Gerontol.Nurs.20,33.11R.Li et al./Journal of Affective Disorders139(2012)1–11。