Cervical spine dysfunctions in patients with chronic subjective tinnitus

支架成形术治疗横窦狭窄继发搏动性耳鸣1例

【 K e y w o r d s 】 p u l s a t i l e t i n n i t u s ; t r a n s v e l ’ s e s i n u s n o s i s ; i n t r a - r a n i a l h y p e l ’ l e i i s i o l l : s t e n t i n g a l i g i o p l a s t y

C o r r e s l mt 7 d i n g n H t h o r :. i f n L o n g,E一 , ¨ “ i l :l o t i g e r g @h o t oa t i l . r 『 J , ¨ ( J[ n t e r v e n t Ra d M ,2 0 1 7.2 6:7 6 5 — 7 6 6)

呜患者 , 此 后 内外 相 天研 究较 少 现 报 道 应 J L } { 支架 成 形术 成功 治 疗 横实 狭 窄继 发 颅 高 压 及 搏 动 性 呜 患 并 J 例

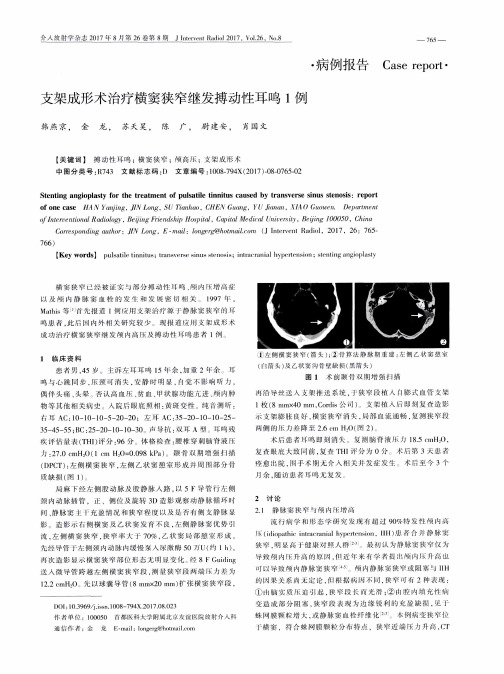

l左 侧 横 窦 狭 窄 ( 筒 头) ; 骨舞 : 法 静 脉 期 重建 : 左侧 乙 状 窦

1 临 床 资 料

St e nt i ng ang i o pl a s t y f o r t he t r e a t m ent o f p ul s at i l e t i nni t us c a us e d by t r a ns ve r s e s i n us s t e nos i s: r ep or t

患者男 , 4 5岁 主 诉序 耳 呜 l 5 余. 加 重 2年 余 耳

鸣 与心 跳 同 步 , 压颈 町消失 . 安静时 明 . r 1 觉 影 响 听 力, 偶伴头痛 、 大晕 、 ’ 否认高 1 0 【 ¨ { 、 贫I 血、 状腺功能亢进 、 颅I ~肿 物 等 其 他 棚 关 史 。入 院 后 底 照 卡 H : 越 斑 变 性 纯 啬 i J ! ! l J 昕:

每天两次氮斯汀喷鼻剂治疗季节性过敏性鼻炎的药用疗效外文翻译原文

R E V I E W Effectiveness of twice daily azelastine nasal spray in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitisFriedrich HorakMedical University Vienna,ENT – Univ. Clinic, Vienna, Austria Correspondence: Friedrich Horak HNO – Univ. Klinik Wien, Waehringer Guertel 18–20, A-1090 Vienna, A ustria T el +43 1 404 003 336Fax +43 1 789 76 76Email friedrich.horak@vienna.at Abstract: Azelastine nasal spray (Allergodil®, Lastin®, Afl uon®; Meda AB, Stockholm, Sweden) is a fast-acting, effi cacious and well-tolerated H1-receptor antagonist for the treatment of rhinitis. In addition it also has mast-cell stabilizing and anti-infl ammatory properties, reducing the concentration of leukotrienes, kinins and platelet activating factor in vitro and in vivo, as well as infl ammatory cell migration in rhinitis patients. Well-controlled studies in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR), perennial rhinitis (PR) or vasomotor rhinitis (VMR) confi rm that azelastine nasal spray has a rapid onset of action, and improves nasal symptoms associated with rhinitis such as nasal congestion and post-nasal drip. Azelastine nasal spray is effective at the lower dose of 1 spray as well at a dose of 2 sprays per nostril twice daily, but with an improved tolerability profi le compared to the 2-spray per nostril twice daily regimen. Compared with intranasal corticosteroids, azelastine nasal spray has a faster onset of action and a better safety profi le, showing at least comparable effi cacy with fl uticasone propionate (Flonase®; GSK, USA), and a superior effi cacy to mometasone furoate (Nasonex®; Schering Plough, USA). In combination with fl uticasone propionate, azelastine nasal spray exhibits greater effi cacy than either agent used alone, and this combination may provide benefi t for patients with diffi cult to treat seasonal allergic rhinitis. In addition, azelastine nasal spray can be used on an as-needed basis without compromising clinical effi cacy. Compared with oral antihistamines, azelastine nasal spray also demonstrates superior effi cacy and a more rapid onset of action, and is effective even in patients who did not respond to previous oral antihistamine therapy. Unlike most oral antihistamines, azelastine nasal spray is effective in alleviating nasal congestion, a particularly bothersome symptom for rhinitis sufferers. Azelastine nasal spray is well tolerated in both adults and children with allergic rhinitis. Bitter taste which seems to be associated with incorrect dosing technique is the most common side effect reported by patients, but this problem can be minimized by correct dosing technique.Keywords: azelastine nasal spray, rhinitis, intranasal corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, seasonal allergic rhinitisIntroductionRhinitis is an inflammatory disease of the upper airways, affecting approximately 58 million people only in the United States alone (Settipane 2001) and its prevalence is increasing. The cost of the disease is signifi cant with between US$2 and US$5 billion incurred annually in both direct and indirect costs (Ray et al 1999; Reed et al 2004). In the US, the number of lost workdays is estimated as approximately 3.5 million a year (Mahr and Sheth 2005). It can be classifi ed as allergic, non-allergic or mixed upper respiratory disorder (Berstein 2007). It is classifi ed as allergic if symptoms occur in association with a specifi c IgE-mediated response; as non-allergic if symptoms are induced by irritant triggers, but without an IgE-mediated response; and as of mixed etiology if IgE-mediated responses occur in conjunction with symptoms induced by both allergens and non-allergic irritant triggers. Allergic rhinitis (AR) is further classifi ed as seasonal or perennial (Dykewicz et al 1998). Seasonal allergic rhinitis© 2008 Dove Medical Press Limited. A ll rights reservedTherapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4(5) 1009–10221009Horak(SAR) symptoms are induced by exposure to pollens from trees, grass, weeds or seasonal mould spores, whilst peren-nial rhinitis (PR) is associated with environmental allergens which are generally present on a year-round basis such as house dust, animal dander and insect droppings (Dykewicz et al 1998). In contrast, the “Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines” recommend a classifi cation in intermittent allergic rhinitis and persistent allergic rhinitis according to the frequency and persistence of symptoms (Bousquet et al 2001).Symptoms of SAR include nasal congestion, runny nose, nasal and nasopharyngeal itching, ear symptoms, sneezing and ocular symptoms in many patients, including itchy and watery eyes (Bielory and Ambrosio 2002). The symptoms of sneezing, itching and rhinorrhea are less common with PR (Economides and Kaliner 2002). As many as half of all patients diagnosed with rhinitis have non-allergic disease (sometimes called vasomotor rhinitis [VMR]) where an allergic component cannot be identifi ed (Dykewicz et al 1998). Symptoms are often induced by irritant triggers such as tobacco smoke, strong odors and temperature and pres-sure changes (Devyani and Corey 2004). The symptoms of VMR are similar to those of AR (Devyani and Corey 2004). To further complicate rhinitis classifi cation, as many as half of all patients with AR are also sensitive to non-allergic triggers; a condition referred to as mixed rhinitis (Settipane and Settipane 2002; Liberman et al 2005). Symptoms of rhinitis can have a major impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL) by interfering with sleep which causes fatigue, and impairing daily activities and cognitive function (Dykewicz et al 1998). Patients often complain of an inability to concentrate, and in the case of SAR often avoid outdoor activities in order to avoid exposure to symptom-inducing allergen(s). The Joint Task Force on Allergy Practice and Parameters advises that improving the negative impact on daily life in rhinitis patients defi nes successful treatment as much as providing symptom relief (Dykewicz et al 1998). Indeed, Juniper (1997) recommends that for most patients with rhinitis, improving patient well-being and QoL should be the primary goal of treatment.Treatment guidelines from the Joint Task Force and WHO recommend that antihistamines, both topical (eg, azelastine [Allergodil®; Meda AB, Stockholm, Sweden]) and oral second-generation (eg, loratadine [Claritin®, Schering Plough, USA], desloratadine [Clarinex®; Schering Plough, USA], fexofenadine [Allegra®; Sanofi Aventis, USA] or cetirizine [Zyrtec®; Pfi zer, USA], and levocetirizine [Xyzall®; UCB, EU]) be used as fi rst-line therapy for AR (Dykewicz et al 1998; Bousquet et al 2001). Intranasal corticosteroids (eg, fl uticasone propionate [Flonase®, GSK, USA], mometasone furoate [Nasonex®; Schering Plough, USA]) may also be considered as initial therapy for AR in patients with more severe symp-toms, particularly nasal congestion [(Dykewicz et al 1998; LaForce 1999). The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines recommend a stepped approach to therapy based upon the frequency and severity of symptoms (Table 1) (Bousquet et al 2001). Interestingly, a recent US nationwide survey incorporating approximately 2500 adult allergy suf-ferers, revealed that 66% were dissatisfi ed with their current allergy medication due to lack of effectiveness (Anon 2006). Furthermore, more than two-thirds of primary care physicians reported patient dissatisfaction with therapy as the main reason for stopping or switching medications (Anon 2001). Clearly, effective therapies with a good safety profi le are needed to treat AR sufferers.AzelastineAzelastine nasal spray is a topically administered second-generation antihistamine and selectively antagonizes the H1-receptor (Zechel et al 1981) being approximately tenfold more potent than chlorpheniramine in this regard (Casale 1989). It has one of the fastest onsets of action (15 min with nasal spray and up to 3 min with eye drops) among the currently available rhinitis medications (Baumgarten et al 1994; Greiff et al 1997). The effect of azelastine lasts at least 12 hours, thus allowing for a once or twice daily dosing regimen (Greiff et al 1997). It has proven effi cacy in treating both allergic and non-allergic rhinitis, and is the only pre-scription antihistamine approved in the US, Portugal and the Netherlands for the treatment of both SAR (1996) and VMR (1999). In SAR patients azelastine therapy (two sprays per nostril twice daily), improved both total symptom and major symptom complex scores to a signifi cantly greater extent than placebo (McTavish and Sorkin 1989; Storms et al 1994; LaForce et al 1996; Ratner and Sacks 2007). Similarly, in PR patients, azelastine nasal spray signifi cantly improved sleep-ing, reduced daytime somnolence and nasal congestion com-pared with placebo (Golden et al 2000). Liberman et al (2005) were the fi rst to show that azelastine was also effective in the management of VMR and even in mixed rhinitis. Azelastine nasal spray signifi cantly (p Ͻ 0.01) reduced the total VMR symptom score (TVRSS) compared with placebo after 21-day double-blind treatment, and was associated with clinical improvement in each symptom of the TVRSS (ie, rhinorrhea, sneezing, nasal congestion, and post-nasal drip). In a large open-label trial 4364 patients received azelastine nasal sprayTherapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4(5)1010Azelastine nasal spray(2 sprays per nostril twice daily) as monotherapy for 2 weeks. 78% of VMR patients reported some or complete control of post-nasal drip which rose to 90% of SAR patients for the symptom of sneezing. Of patients reporting sleep diffi culties or impaired daytime activities because of rhinitis symptoms, 85% experienced improvements in these parameters with azelastine. Baseline sleep diffi culties and impairment of daytime activities were signifi cant (p Ͻ 0.01) predictors of a positive treatment effect with azelastine nasal spray. Female patients (p = 0.02), patients with SAR (p Ͻ 0.01) and patients with SAR plus sensitivity to non-allergic triggers (p = 0.03) were identifi ed as being most likely to respond to azelastine nasal spray (Liberman et al 2005) Due to its rapid onset of action, azelastine nasal spray continues to control rhinitis symptoms when used on an as-needed basis (Ciprandi et al 1997). This property of azelastine is discussed later. First marketed in the UK in 1991 for the treatment of both SAR and PR, it is currently available in more than 70 countries world-wide.Mode of actionH owever, azelastine is more than just an anti-histamine. It exhibits a very fast and long-acting effect based on a triple mode of action, with anti-infl ammatory and mast cell stabilizing properties in addition to its anti-allergic effects (Bernstein 2007; Lee and Corren 2007). For example, azelas-tine inhibits the activation of cultured mast cells and release of interleukin (IL)-6, tryptase, and histamine (Kempuraj et al 2002). It also reduces mediators of mast cell degranu-lation such as leukotrienes which are involved in the late phase allergic response (Howarth 1997), in the nasal lavage fl uid of patients with rhinitis (Shin et al 1992). It does this possibly by reducing the production of leukotriene (LT)B4 and LTC4, inhibiting phospholipase A2and LTC4synthase (H amasaki et al 1996). Leukotrienes are associated with dilation of vessels, increased vascular permeability and edema which results in nasal congestion, mucus production and recruitment of infl ammatory cells (Golden et al 2006). Substance P and bradykinin concentrations which are formed in biological fl uids and tissues during infl ammation, are also reduced by azelastine (Shin et al 1992; Nieber et al 1993; Shinoda et al 1997). These agents are associated with the AR symptoms of nasal itching and sneezing, but may also contribute to the onset of non-allergic VMR symptoms. Other anti-infl ammatory properties of azelastine include inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) releaseT able 1 Summary of ARIA allergic rhinitis management guidelinesRhinitis severity ARIA recommendationMild intermittent • Oral/intranasal antihistamines OR• Decongestants (10 days maximum)Moderate/severe intermittent • Intranasal antihistamines• Oral antihistamines AND/OR• Decongestants• Intranasal corticosteroids• CromonesMild persistent • Intranasal antihistamines• Oral antihistamines AND/OR• Decongestants• Intranasal corticosteroids• CromonesA stepwise approach is advised with reassessment after 2 weeks. If symptomsare controlled and the patient is on intranasal corticosteroid, the dose shouldbe reduced, but otherwise treatment continued. If symptoms persist and thepatient is on antihistamines or cromones, a change should be made to anintranasal corticosteroid.Moderate/severe persistent • Intranasal corticosteroid (fi rst line treatment)If symptoms are uncontrolled after 2–4 weeks, medication should be addeddepending on the persistent symptom, eg, add an antihistamine if the majorsymptom is rhinorrhea, pruitis, or sneezing, double the dose of intranasalsteroid for persistent nasal blockage and add ipratropium for prominentcomplaint of rhinorrhea.Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4(5)1011Horak(Hide et al 1997; Matsuo and Takayama 1998), reduction of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) generation, as well as a reduction in the number of a range of infl ammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-4 and IL-8 (Y oneda et al 1997; Ito et al 1998; Beck et al 2000). These cytokines perpetuate the infl ammatory response (Settipane 2001). Finally, in SAR patients, azelastine nasal spray has been shown to lower neutrophil and eosinophil counts and decrease intercel-lular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression on nasal epithelial cell surfaces in both the early and late phases of the allergic reaction (Ciprandi et al 1996). It also decreases free-radical production by human eosinophils and neutrophils (Busse et al 1989; Umeki 1992) and calcium infl ux induced by platelet-activating factor in vitro (Nakamura et al 1988; Morita et al 1993).The use of a topical treatment has many advantages over a systemic treatment. Firstly, with a nasal spray, medication can be delivered directly to the site of allergic infl ammation. Secondly, the higher concentrations of antihistamines that can be achieved in the nasal mucosa by topical as opposed to oral administration should enhance the anti-allergic and potential anti-infl ammatory effects of these agents. Thirdly, a dose of 0.28 mg intranasally has a faster onset of action than a dose of 2.2 mg administrated orally (Horak et al 1994). And fi nally, with topical administration the risk of interaction with concomitant medication is minimized (Davies et al 1996) and the potential of systemic effects reduced.DosageRecent results from 2 studies have shown that azelastine nasal spray at a dosage of 1 spray per nostril twice daily is effec-tive and has a better tolerability profi le compared to 2 sprays per nostril twice daily in patients (Ն12 years; n = 554) with moderate to severe SAR (Lumry et al 2007). The total nasal symptom score (TNSS) improved by 14.1% in study 1 and by 22.1% in study 2 with azelastine nasal spray (1 spray per nostril twice daily) compared with 4.5% and 12.0% with placebo in study 1 (p = 0.01) and 2 (p Ͻ 0.01) respectively. This compares with a 24%–29% improvement in rhinitis symptoms scores with a 2-spray dosage of azelastine (Ratner et al 1994; Storms et al 1994; LaForce et al 1996). For individual symptoms, itchy nose, runny nose, sneezing, and nasal congestion were all signifi cantly improved after the 1-spray azelastine regimen compared with placebo. One spray per nostril twice daily of azelastine was also associ-ated with signifi cant improvements in the Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) daily activity and nasal symptoms domains and patient global evaluations compared with placebo. In addition, the incidence of a bitter taste after azelastine application more than halved and the incidence of somnolence decreased almost 30 times in the 1-spray group versus the labeled incidence with the 2-spray regimen (Lumry et al 2007). Although an earlier study showed an improve-ment in rhinitis symptoms versus placebo with azelastine 1 spray per nostril twice daily, this improvement failed to reach statistical signifi cance. However, a global evaluation noted a signifi cant clinical improvement versus placebo (49%) in the 1-spray regimen (75%, p Ͻ 0.001) as well as a 2-spray once daily (89%, p = 0.028) and a 2-spray twice daily regimen (83%, p Ͻ 0.001) (Weiler et al 1994).From these results one can conclude that a greater degree of effectiveness would be expected with two sprays per nostril twice daily. Although one spray per nostril twice daily may provide somewhat less effi cacy this is compensated for by an improved tolerability profi le compared with the 2-spray regimen. Therefore, the choice of dosage of azelastine nasal spray should be based on the severity and persistence of symptoms as well as the patient’s acceptance of the nasal spray (Bernstein 2007). For example, the 2-spray dose could be used as the starting dose for patients with severe symptoms of SAR, and either maintained or tapered to the 1-spray dose as required. The 1-spray dose could be used as a starting dose in patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms, and if necessary the dose increased to 2 sprays per nostril twice daily if symptom control proved to be inadequate (Lumry et al 2007).As-neededBecause azelastine starts working within 15 minutes of application investigators wondered how effective an as-needed regimen would be in controlling the symptoms of rhinitis (Ciprandi et al 1997). A randomized controlled study was car-ried out in 30 patients sensitized to Parietaria pollen or grass. Patients were treated with the standard European dose of azelas-tine (0.56 mg/day), half this dose (0.22 mg/day), or as-needed. Both groups who received the standard and half-standard doses showed an improvement in their rhinitis symptoms, with a concomitant reduction in markers of infl ammation, namely neutrophil and eosinophil counts as well as ICAM-1 expression in nasal scrapings. However, patients who used azelastine nasal spray on an as-needed basis also showed an improvement in their rhinitis symptoms, but without a reduction in the markers of infl ammation. The results of this small study suggest that although regular treatment with azelastine is superior at controlling symptoms, as-needed therapy may beTherapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4(5)1012Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4(5)1018Horakan improvement in TNSS of 32.5% compared with 24.6% for those patients taking oral cetirizine. The most common side effect reported by patients in the azelastine group was bitter taste (5.7%). Somnolence was reported by 1.5% of patients taking cetirizine (Sher and Sacks 2006).In addition to nasal symptoms, patients with SAR can experience impairment in HRQoL. Two 2-week, double-blind, multicenter studies were conducted during autumn 2004 and spring 2005 comparing the improvement with azelastine nasal spray (2 sprays per nostril twice daily) versus cetirizine (10 mg daily) on symptoms and HRQoL in SAR patients (Meltzer and Sacks 2006). Results from these studies revealed that azelastine nasal spray improved the overall RQLQ score to a signifi cantly (p Ͻ 0.05) greater degree than cetirizine tablets. When results from both studies were pooled, the combined analysis confi rmed the signifi cant superiority of azelastine spray both in terms of the overall RQLQ score (p Ͻ 0.001) as well as each RQLQ domain (p Ͻ 0.03) including the nasal symptoms domain (p Ͻ 0.001). More patients in the azelastine nasal spray group experienced a clinically important improve-ment from baseline in HRQoL (ie, Ն2 units on the 0–6 rating scale) compared with patients in the cetirizine group (35% vs 20% respectively) (Meltzer and Sacks 2006).Berger et al (2006) also showed that azelastine nasal spray (2 sprays per nostril) and oral cetirizine (10 mg once daily) effectively treated nasal symptoms in patients with SAR (n = 360). Rapid relief of rhinitis symptoms was evident in both groups at the fi rst evaluation after initial administration and continued during the 14 study days, with the azelastine patients showing the greatest degree of improvement during the second week of treatment. Improvements in the TNSS and individual symptoms favored azelastine over cetirizine (Figure 7), with signifi cant differences for nasal congestion (p = 0.049) and sneezing (p = 0.01). Azelastine nasal spray improved TNSS by a mean of 4.6 (23.9%) compared with 3.9 (19.6%) with cetirizine. The positive effect of azelastine nasal spray on congestion was observed despite the fact that the cetirizine group had the added benefi t of daily use of a placebo saline spray. Azelastine nasal spray also signifi cantly improved the RQLQ overall (p = 0.002) and individual domain (p Յ 0.05) scores compared with cetirizine (Berger et al 2006). Although oral cetirizine signifi cantly improved RQLQ scores, patients treated with azelastine nasal spray reported additional statistically signifi cant improvement beyond that reported with cetirizine for each individual RQLQ domain including activities, sleep, non-nose/non-eye symp-toms, practical problems, nasal symptoms, eye symptoms, and emotions (Figure 8). Although it is often assumed that patients prefer oral medications to sprays in both the ACT I and ACTII trials, patients reported superior improvements in QoL variables with azelastine nasal spray compared with oral cetirizine (Corren et al 2005).MNSS Rhinorrhea Nasal Itching Sneezing Nasal Congestion1234AzelastineDesloratadine PlaceboA b s o l u t e I m p r o v e m e n t f r o m b a s e l i n e(120 m i n s c o r e –360 m i n s c o r e )Figure 6 Major nasal symptom and mean nasal symptom scores after administration of azelastine nasal spray (1 spray per nostril), desloratadine (5 mg) or placebo in patients with SAR: absolute changes of last value (6 hours after the start of challenge) compared to predose (ie, 2 hours after the start of the challenge). Reprinted with permission from Horak F , Zieglmayer UP , Zidglmayer R, et al 2006. A zelastine nasal spray and desloratadine tablets in pollen-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis: a pharmacodynamic study of onset of action and ef fi cacy. Curr Med Res Opion , 22:151–7. Copyright © 2006 LibraPharm.as either ‘good’ or ‘very good’ compared with just 76% of levocabastine patients (Falser et al 2001).Safety and tolerabilityThe advantages of intranasal delivery include lower risk of systemic side effects and drug interactions (Salib and Howarth 2003). In controlled studies, azelastine nasal spray was well-tolerated for treatment durations up to 4 weeks in both adults and children (Ն12 years) (Storms et al 1994; Meltzer et al 1994; Ratner et al 1994; Weiler et al 1994; LaForce et al 1996). Bitter taste, headache, somnolence and nasal burning were the most frequently reported adverse events, but most of these were mild or moderate in nature. These studies reported a greater incidence of somnolence compared with placebo (11.5% vs 5.4%, p Ͻ 0.05). How-ever, the incidence of somnolence between azelastine- and placebo-treated patients (3.2% vs 1.0%) did not differ in VMR studies (Banov and Liberman 2001). Post-marketing surveillance studies also reported a similar degree of somnolence (approx 2%) in both azelastine and placebo groups (Berger and White 2003; LaForce et al 2004; Corren et al 2005; Berger et al 2006). The lower incidence of azelastine-related adverse events in later trials is most likely due to correct dosing technique, when the drug is administered without tipping back the head or deeplyinhaling the spray, both of which would increase systemic absorption and could result in bitter taste and somnolence. As the incidence of somnolence whilst using azelastine nasal spray has been reported to be greater than placebo in certain studies, US prescribing recommendations warn against concurrent use of alcohol and/or other CNS sup-pressants. However, to date no studies have been designed to assess specifi cally the effects of azelastine nasal spray on the CNS in humans.DisclosuresThe author has no confl icts of interest to report.AbbreviationsACT 1, first Azelastine Cetirizine Trial; AR, allergic rhinitis; ARIA, allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma; EEC, environmental exposure chamber; GM-CSF, granu-locyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; H RQoL, health-related quality of life; ICAM-1, intercellular adhe-sion molecule-1; IL, interleukin; LT, leukotriene; MNSS, major nasal symptom score; NNT, number needed to treat; PR, perennial rhinitis; QoL, quality of life; RQLQ, Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire; SAR, seasonal allergic rhinitis; TNF α, tumor necrosis factor alpha;Azelastine nasal spray Cetirizine21.510.5M e a n i m p r o v e m e n t f r o m b a s e l i n eOverall RQLQ ScoreActivities SleepNon-nasal non-eye symptomsPractical problems Nasal symptoms Eye symptoms EmotionFigure 8 Mean improvement from baseline to day 14 in overall Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) score and individual RQLQ domain scores (intention-to-treat population). *p Յ 0.05 vs cetirizine; **p Ͻ 0.01 vs cetirizine. Reprinted with permission from Berger W , Hampel F , Bernstein J, et al 2006. Impact of azelastine nasal spray on symptoms and quality of life compared with cetirizine oral tablets in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol , 97:375–81. Copyright © 2006 American College of Allergy, A sthma and Immunology.TNSS, total nasal symptom score; TVRSS, Total VMR Symptom Scale; VCC, Vienna Challenge Chamber; VMR, vasomotor rhinitis.ReferencesAl Suleimani YM, Walker MJA. 2007. Allergic rhinitis and its pharmacology.Pharmacol Ther, 114:233–60.Anon. 2001. Physician survey sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Rochester (NY): Harris Interactive Inc, October 19–21.Anon. 2006. Allergies in America: a landmark survey of nasal allergy sufferers. H ealthSTAR Communications, Inc. Sponsored by Altana Pharma US, Inc. March 1.Banov CH, Liberman P. 2001. Effi cacy of azelastine nasal spray in the treatment of vasomotor (perennial nonallergic) rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 86:28–35.Baumgarten CR, Petzold U, Dokic D, et al. 1994. Modifi cation of allergen-induced symptoms and mediator release by intranasal azelastine.J Pharmacol Ther, 3:43–51.Beck G, Mansur A, Afzal M, et al. 2000. Effect of azelastine nasal spray on mediators of infl ammation in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR). American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 56th Annual Meeting, San Diego (CA); March 3–8.Behncke VB, Alemar GO, Kaufman DA, et al. 2006. Azelastine nasal spray and fl uticasone nasal spray in the treatment of geriatric patients with rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 117:263Berger W, Hampel F, Bernstein J, et al. 2006. Impact of azelastine nasal spray on symptoms and quality of life compared with cetirizine oral tablets in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 97:375–81.Berger WE, White MV. 2003. Effi cacy of azelastine nasal spray in patients with an unsatisfactory response to loratadine. An n Allergy Asthma Immunol, 91:205–11.Berkowitz TB, Bernstein DI, LaForce C, et al. 1999. Onset of action of mometasone furoate nasal spray (NASONEX) in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy, 54:64–9.Bernstein JA. 2007. Azelastine hydrochloride: a review of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, clinical effi cacy and tolerability. Curr Med Res Opin, 23:2441–52.Bielory L, Ambrosio P. 2002. Conjunctivitis and allergic eye diseases. In: Kaliner MA, editor. Current Reviews of Rhinitis. Philadelphia: Current Medicine, Inc. pp. 115–22.Bousquet J, van Cauwenberge PB, Khaltaev N, et al. 2001. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma: ARIA workshop report. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 108:S147–S334.Busse W, Randley B, Sedgwick J, et al. 1989. The effect of azelastine on neutrophil and eosinophil generation of superoxide. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 83:400–5.Casale TB. 1989. The interaction of azelastine with human lung histamine H1, beta, and muscarinic receptor binding sites. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 83:771–6.Charlesworth EN, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. 1989. Effect of cetirizine on mast cell-mediator release and cellular traffi c during the cutaneous late-phase reaction. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 83:905–12. Cheria-Sammari S, Aloui R, Gormand B, et al. 1995. Leukotriene B4 pro-duction by blood neutrophils in allergic rhinitis: effects of cetirizine.Clin Exp Allergy, 25:729–36.Ciprandi G, Buscaglia S, Pesce G, et al. 1995. Cetirizine reduces infl amma-tory cell recruitment and ICAM-1 (or CD54) expression on conjunctival epithelium in both early-and late-phase reactions after allergen-specifi c challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 95:612–21.Ciprandi G, Pronzato C, Passalacqua G, et al. 1996. Topical azelastine reduces eosinophil activation and intercellular adhesion molecule-I expression on nasal epithelial cells: an anti-allergic activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 98:1088–96.Ciprandi G, Ricca V, Passalaqua G, et al. 1997. Seasonal rhinitis and azelastine: long- or short-term treatment? J Allergy Clin Immun ol, 99:301–7.Corren J, Storms W, Bernstein J, et al. 2005. Effectiveness of azelastine nasal spray compared with oral cetirizine in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Ther, 27:543–53.Davies RJ, Bagnall AC, McCabe RN, et al. 1996. Antihistamines: topical vs oral administration. Clin Exp Allergy, 26:S11–S17.Devyani L, Corey JP. 2004. Vasomotor rhinitis update. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 12:243–247.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, et al. 1998. Diagnosis and manage-ment of rhinitis: complete guidelines of the Joint ask Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 81:478–518.Economides A, Kaliner MA. 2002. Allergic rhinitis. In: Kaliner MA, ed.Current Reviews of Rhinitis. Philadelphia: Current Medicine, Inc.pp. 35–51.Falser N, Wober W, Rahlfs VW, et al. 2001. Comparative effi cacy and safety of azelastine and levocabastine nasal sprays in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Arzeimittelforschung, 51:387–93.Golden MP, Gleason MM, Togias A. 2006. Cysteinyl leukotrienes: multi-functional mediators in allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy, 36:689–703.Golden S, Teets SJ, Lehman EB, et al. 2000. Effect of topical nasal azelastine on the symptoms of rhinitis, sleep and daytime somnolence in perennial allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 85:53–7.Greiff L, Andersson M, Svensson C, et al. 1997. Topical azelastine has a 12-hour duration of action as assessed by histamine challenge-induced exudation of alpha 2-macroglobulin into human nasal airways. Clin Exp Allergy, 27:438–44.Hamasaki Y, Shafi geh M, Y amamoto S, et al. 1996. Inhibition of leukotriene synthesis by azelastine. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 76:469–75. Herman D, Garay R, Legal M. 1997. A randomized double-blind placebo controlled study of azelastine nasal spray in children with perennial rhinitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 39:1–8.H ide I. Toriu N, Nuibe T, et al. 1997. Suppression of TNF-α secre-tion by azelastine in a rat mast (RBL-2H3) cell line. J Immun ol, 159:2932–40.Horak F, Jager S, Toth J, et al. 1994. Azelastine in pollen-induced allergic rhinitis – a pharmacodynamic study of onset of action and effi cacy.Drug Invest, 7:34–40.Horak F, Stübner P, Zieglmayer R, et al. 2003. Comparison of the effect of Desloratadine 5mg daily and placebo on nasal airfl ow and seasonal allergic rhinitis symptoms induced by grass pollen exposure. Allergy, 58:481–5.H orak F, Stübner P. 2002. Decongestant activity of deslorata-dine in controlled-allergen-exposure trials. Clin Drug In vest, 22(Suppl 2):13–20.Horak F, Stübner UP, Zieglmayer R, et al. 2002a. Effect of desloratadine versus placebo on nasal airfl ow and subjective measures of nasal obstruction in patients with grass pollen-induced allergic rhinitis in an allergen-exposure unit. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 109:956–61.Horak F, Stübner UP, Zieglmayer R, et al. 2002b. Effect of desloratadine versus placebo on nasal airfl ow and subjective measures of nasal obstruction in subjects with grass pollen-induced allergic rhinitis in an allergen-exposure unit. J Allergy Clin. Immunol, 109:956–61.Horak F, Zieglmayer UP, Zieglmayer R, et al. 2006. Azelastine nasal spray and Desloratadine tablets in pollen-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis:a pharmacodynamic study of onset of action and effi cacy. Curr MedRes Opion, 22:151–7.Howarth PH. 1997. Mediators of nasal blockage in allergic rhinitis. Allergy, 52(Suppl 40):12–8.Ito H, Nakamura Y, Takagi S, et al. 1998. Effects of azelastine on the level of serum interluekin-4 and soluble CD23 antigen in the treatment of nasal allergy. Arzneim-Forsch, 48:1143–7.Juniper EF. 1997. Measuring health-related quality of life in rhinitis.J Allergy Clin Immunol, 99:S742–S9.。

调神开郁针法结合眼针治疗紧张性头痛的临床观察

中国临床保健杂志 2021年6月第24卷第3期 ChinJClinHealthc,June2021,Vol.24,No.3·论著·调神开郁针法结合眼针治疗紧张性头痛的临床观察刘丹1,张亭玉2,于春华3,张艺馨21.黑龙江中医药大学附属第一医院针灸四科,哈尔滨150040;2.黑龙江中医药大学;3.黑龙江省哈尔滨仁济中医门诊部[摘要] 目的 观察调神开郁针法结合眼针治疗紧张性头痛的临床疗效。

方法 采用随机数字表法将紧张性头痛患者60例分为观察组和对照组各30例,观察组予调神开郁针法与眼针结合的治疗方案,对照组予常规针刺方案,均治疗4个疗程后运用统计学方法对两组患者的头痛情况(头痛程度、持续时间、头痛指数)、焦虑抑郁情况的评价指标及临床疗效进行分析。

结果 观察组患者治疗后视觉模拟评分法(VAS)评分、头痛持续时间、头痛指数均较治疗前明显降低(P 0.01),且与对照组比较差异均有统计学意义(P 0.01)。

对照组患者治疗后VAS评分较治疗前降低(P 0.05),头痛持续时间、头痛指数均较治疗前明显降低(P 0.01);两组治疗后汉密尔顿焦虑量表(HAMA)、汉密尔顿抑郁量表(HAMD)评分均较治疗前明显降低(P 0.01),且治疗后的HAMA评分与对照组比较差异有统计学意义(P 0.01),HAMD评分组间比较差异有统计学意义(P 0.05)。

观察组总有效率为93.3%优于对照组的76.7%,两组临床疗效比较,差异有统计学意义(P 0.05)。

结论 调神开郁针法结合眼针治疗紧张性头痛,可明显降低患者头痛程度、持续时间、头痛指数,改善患者焦虑、抑郁的不良精神心理状态效果优于常规针刺。

[关键词] 紧张型头痛;针灸疗法;眼针;治疗结果DOI:10.3969/J.issn.1672 6790.2021.03.010ClinicalobservationofTiaoShenKaiYuNeedingcombinedwithEyeAcupunctureinthetreatmentoftensiontypeheadacheLiuDan ,ZhangTingyu,YuChunhua,ZhangYixinDepartmentofAcupunctureⅣ,theFirstAffiliatedHospitalofHeilongjiangUniversityofChineseMedicine,Harbin150040,China[Abstract] Objective ToobservetheclinicaleffectofTiaoShenKaiYuNeeding(anti depressionandregulatingmind)combinedwitheyeacupunctureontension typeheadache.Methods Atotalof60patientswithtension typeheadachewererandomlydividedintoobservationgroupandcontrolgroupaccordingtotherandomnumbertablemethod,30casesineachgroup.TheobservationgroupwastreatedwiththecombinationofTiaoShenKaiYuNeedingandeyeacupuncturewhilethecontrolgroupwastreatedwiththeconventionalacupuncture.After4coursesoftreatment,theresultsoftheheadachestatus(headachedegree,duration,headacheindex),theevaluationindexesofanxietyanddepressionandtheclinicalefficacyoftwogroupswereanalyzedbystatisticalmethods.Results Afterthetreatment,VASscore,headachedurationandheadacheindexintheobservationgroupweresignificantlylower(P 0.01),andthedifferencesbetweengroupsweresignificance(P 0.01).Inthecontrolgroup,VASscorewaslower(P 0.05),headachedurationandheadacheindexweresignificantlylower(P 0.01)afterthetreatment.TheHAMAandHAMDscoresofthetwogroupsweresignificantlylowerthanthosebeforetreatment(P 0.01),thebetween groupdifferenceofHAMAscorehasobvioussignificance(P 0.01),andHAMDscorehasstatisticalsignificance(P 0.05).Thetotaleffectiveratewas93.3%intheobservationgroupand76.7%inthecontrolgroup,andthedifferenceinclinicalefficacybetweenthetwogroupswasstatisticallysignificant(P 0.05).Conclusion TheefficacyofTiaoShenKaiYuNeedingcombinedwitheyeacupunctureinthetreatmentoftension typeheadacheisbetterthanthatofconventionalacupuncture,whichcansignificantlyreducetheheadachedegree,duration,headacheindexofpatients,andimprovetheadversementalandpsychologicalstatesofanxietyanddepression.[Keywords] Tension typeheadache;Acupuncture Moxibustion;Eyeacupuncture;Treatmentoutcome基金项目:第四批全国中医(临床、基础)优秀人才研修项目(国中医药人教发〔2017〕24号)作者简介:刘丹,主任医师,硕士研究生导师,Email:gameckld@126.com 紧张性头痛(TTH)主要表现为双侧颈枕部、额颞部或全头部发作性甚至持续性的紧缩感、压迫感或钝痛感。

浅谈咽鼓管功能障碍的诊治

123 45 6 7

5 Crackling or popping sounds in the ear?

123 45 6 7

6 Ringing in the ears.

123 45 6 7

7 A feeling that your hearing is muffled.

123 45 6 7

治疗

• 治疗: 一、咽鼓管异常开放 1、一般治疗; 2、药物治疗:局部激素、局部封闭、鼻冲洗等。 3、手术治疗:咽鼓管咽口黏膜下注射、咽鼓管咽口热凝术

5 Schroder S, Lehmann M, Ebmeyer J, er al. Balloon Eustachian tuboplasty: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Clin Otolaryngol, 2015,40(6): 629-638. 6 易虹, 谢杏强. 咽鼓管球囊扩张术对鼻咽癌放疗后分泌性中耳炎的治疗[J]. 实用临床医学, 2017, 18(5): 8182.

其他

无法确定的

临床表现

• 症状: 1.耳闷胀感; 2. 听力下降; 3. 耳鸣; 4. 头痛; 5. 眩晕; 6. 自听增强

客观检查

• 客观检查: 1. 内镜检查:耳内镜、视频内镜、鼻咽镜 2. 声导抗测听:Doyle等[1]研究提示声导抗诊断ETD的灵敏度和特异性分

别为52%和51%。

1. Doyle WJ, Swarts JD, Banks J, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of eustachian tube funtion tests in adults[J]. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2013, 139(7): 719-727.

大前庭水管综合征前庭功能及听力学相关检查的研究与分析

英文缩略词表英文缩写 英文全称 中文名称LV AS large vestibular aqueduct syndrome 大前庭水管综合征 VEMP vestibular evoked myogenic potential 前庭诱发的肌源性电位 SVV subjective visual vertical 主观垂直视觉检查 PTA pure tone audiometry 纯音测听SN Spontaneus nystagmus 自发性眼震CP canal paresis 轻瘫指数OTR ocular tiltreactiong 眼球偏斜反应学位论文原创性声明和版权使用授权书学位论文原创性声明本人郑重声明:所呈交的学位论文,是本人在导师的指导下,独立进行研究工作所取得的真实成果。

除文中已注明引用的内容外,本论文不含任何其他个人或集体已经发表或撰写过的作品成果。

对本论文的研究做出重要贡献的个人和集体,均已在文中以明确方式标明。

本人完全意识到本声明的法律结果由本人承担。

作者签名(手写):__________ 导师签名(手写):_______________________年____月____日 ____________年____月____日学位论文版权使用授权书本学位论文作者完全了解学校有关保留、使用学位论文的规定,同意学校保留并向国家有关部门或机构(如国家图书馆、中国学术期刊电子杂志社的《中国优秀博硕士学位论文数据库》、中国科学技术信息研究所的《中国学位论文全文数据库》等)送交论文的复印件和电子版,允许论文被查阅和借阅。

本人授权福建医科大学可以将本学位论文的全部或部分内容编入有关数据库进行检索,可以采用影印、缩印或扫描等复制手段保存和汇编本学位论文。

(保密的学位论文在解密后适用本授权书)作者签名(手写):__________ 导师签名(手写):_______________________年____月____日 ____________年____月____日第一部分基础篇前庭水管是一微小骨管,位于颞骨岩部中,呈逆转的J型,可分为近侧段和远侧段两部分。

外周前庭疾病的诊断和治疗

收稿日期:2020 ̄08 ̄04基金项目:上海交通大学医工交叉重点项目(ZH2018ZDA11)ꎻ上海交通大学医学院附属新华医院院级临床研究培育基金项目(17CSK03ꎬ18JXO04)通信作者:杨军ꎮE ̄mail:yangjun@xinhuamed.com.cndoi:10.6040/j.issn.1673 ̄3770.1.2020.074述评外周前庭疾病的诊断和治疗杨军ꎬ郑贵亮上海交通大学医学院附属新华医院耳鼻咽喉头颈外科/上海交通大学医学院耳科学研究所/上海市耳鼻疾病转化医学重点实验室ꎬ上海200092㊀㊀杨军ꎬ上海交通大学医学院附属新华医院耳鼻咽喉头颈外科主任ꎬ博士生导师ꎬ上海市优秀学科带头人ꎬBarany协会会员ꎬ中华医学会耳鼻咽喉头颈外科分会耳科组委员ꎬ上海医学会耳鼻咽喉头颈外科分会副主任委员ꎮ中宣部 国家出版基金 项目评审委员会二审专家ꎮ«ActaOto ̄Laryngologica»«中华耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志»«山东大学耳鼻喉眼学报»等八种期刊编委㊁特邀审稿专家ꎮ临床专长为耳神经及侧颅底外科ꎬ在眩晕外科㊁耳神经外科㊁侧颅底肿瘤以及听觉植入方面具有丰富的临床经验ꎻ基础研究方向为耳蜗发育㊁听觉可塑性㊁耳蜗转导机制ꎮ作为项目负责人承担国家自然基金5项㊁973子课题1项㊁上海市科委重大项目1项ꎬ发表论文160余篇ꎮ作为主要完成人ꎬ获得国家科技进步二等奖㊁华夏医学科技奖二等奖㊁上海市科技进步奖一等奖㊁上海医学科技奖一等奖㊁中华医学科技奖三等奖㊁高等学校科学研究优秀成果奖科学技术进步奖一等奖等奖项ꎮ成功申办并将于2021年4月22~25日在上海举办第八届梅尼埃及内耳疾病国际研讨会ꎮ入选中国耳科医生百强榜名录和中国名医百强榜眩晕外科医生名录ꎮ摘要:眩晕是外周前庭疾病的主要表现之一ꎬ发病原因涉及多个学科ꎬ临床诊治较为困难ꎮ随着前庭功能检查技术的发展㊁对前庭疾病研究的不断深入ꎬ相关科研成果与日剧增并广泛应用于临床ꎮ近年来ꎬ随着前庭疾病国际分类标准制定和发布ꎬ各类前庭疾病诊断标准相继出台ꎬ治疗前庭疾病的药物㊁手术的相关规范日趋完善ꎬ加之前庭康复技术的飞速发展ꎬ使得对前庭疾病的诊疗越来越规范和精准ꎮ关键词:外周前庭疾病ꎻ眩晕ꎻ诊疗进展ꎻ前庭功能检查ꎻ前庭康复治疗中图分类号:R764.3㊀㊀㊀文献标志码:A㊀㊀㊀文章编号:1673 ̄3770(2020)05 ̄0001 ̄06引用格式:杨军ꎬ郑贵亮.外周前庭疾病的诊断和治疗[J].山东大学耳鼻喉眼学报ꎬ2020ꎬ34(5):1 ̄6.YANGJunꎬZHENGGuiliang.Diagnosisandmanagementofperipheralvestibulardiseases[J].JournalofOtolaryngologyandOphthalmologyofShan ̄dongUniversityꎬ2020ꎬ34(5):1 ̄6.DiagnosisandmanagementofperipheralvestibulardiseasesYANGJunꎬZHENGGuiliangDepartmentofOtolaryngology ̄Head&NeckSurgeryꎬXinhuaHospitalꎬShanghaiJiaotongUniversitySchoolofMedicine/EarInstituteꎬShanghaiJiaotongUniversitySchoolofMedicine/ShanghaiKeyLaboratoryofTranslationalMedicineonEarandNoseDiseasesꎬShanghai200092ꎬChinaAbstract:Vertigoisoneofthemostimportantsymptomofperipheralvestibulardiseaseswhicharedifficulttodifferentiallydiag ̄noseandmanagebecausemultipledisciplinesareinvolved.Thepremiseofeffectivemanagementisaccuratediagnosisofvestibulardiseases.Withthedevelopmentofvestibularfunctionexaminationtechnologyandthedeepeningofvestibulardiseaseresearchꎬgreatprogresshasbeenmadeinthediagnosisandmanagementofvestibulardiseases.Theestablishmentandpublicationofinternationalclassificationofvestibulardiseasesꎬtheintroductionofdiagnosticstandardsforvariousvestibulardiseasesintheworldꎬtheformula ̄tionofvestibulardiseasedrugsꎬsurgicalspecificationsandtherapiddevelopmentofvestibularrehabilitationtechnologymakethediagnosisandmanagementofvestibulardiseasesmoreandmorestandardizedandaccurate.Keywords:PeripheralvestibulardiseaseꎻVertigoꎻDiagnosisandmanagementꎻVestibularfunctionexaminationꎻVestibularrehabilitationtherapy㊀㊀眩晕作为多感官综合征ꎬ是耳鼻咽喉科门诊就诊的主要症状之一ꎬ涉及耳鼻咽喉科㊁神经内科㊁骨科㊁心内科㊁精神科㊁心理科等多个学科ꎬ临床诊治较为困难[1 ̄2]ꎮ众所周知ꎬ对于任何疾病的准确治疗ꎬ都是以准确的诊断为前提的ꎮ近年来ꎬ随着对前庭疾病研究的深入以及各种前庭检查技术的发展ꎬ在临床各学科的共同关注和努力下ꎬ前庭疾病的国际分类㊁诊疗规范和指南㊁专家共识等相继制定和推出ꎬ使得对前庭疾病的诊断和治疗越来越精准[3 ̄6]ꎮ本文主要从前庭疾病国际分类和规范㊁前庭功能检查技术进展㊁外周前庭疾病的药物和手术治疗㊁前庭康复等四个方面来对外周前庭疾病的诊疗进展进行述评ꎮ1㊀前庭疾病国际分类和规范为了提高临床质量ꎬ加强研究促进学科发展ꎬ世界卫生组织决定在国际疾病分类第11版(interna ̄tionalclassificationofdiseases11ꎬICD ̄11)中首次加入前庭疾病国际分类(internationalclassificationofvestibulardisordersꎬICVD)ꎮICVD的框架结构㊁定义和疾病诊断标准等陆续出台ꎬ于2018年正式发布了完整版本[3]ꎮ在ICVD的框架结构中ꎬ对前庭疾病㊁前庭症状㊁诊断标准等分别进行了界定和定义ꎮ前庭疾病除了包括累及前庭的内耳疾病外ꎬ也涵盖了前庭至脑的传导通路ꎬ包括脑干㊁小脑㊁相关皮层下结构以及前庭皮层的病变[4]ꎻ对于临床症状与前庭疾病类似ꎬ但原发于其他系统的疾病(如心脏㊁颈椎等)ꎬICVD主要集中于这些疾病的前庭表现ꎬ并未重新定义和分类这些非前庭原发疾病ꎮ前庭疾病的分类和定义对促进诊断标准的制定㊁临床医生及研究者的交流㊁疾病治疗及机制研究方面有着重要意义[3]ꎮICVD框架结构由相互关联的四个层面构成[3 ̄4]ꎬ包括症状和体征㊁综合征㊁功能失调和疾病㊁发病机制ꎮ在第一层中对前庭症状分别进行了定义ꎬ包括眩晕㊁头晕㊁前庭-视觉症状㊁姿势症状ꎻ在第二层中对常见的前庭综合征进行了定义ꎬ包括急性㊁发作性㊁慢性前庭综合征ꎻ在第三层中对前庭疾病分别进行了定义ꎬ并制定了前庭性偏头痛(vestibularmigraineꎬVM)㊁良性阵发性位置性眩晕(benignparoxysmalpositionalvertigoꎬBPPV)㊁梅尼埃病(Meniere̓sdiseaseꎬMD)以及持续性姿势知觉性头晕(persistentposturalperceptualdizzinessꎬPPPD)㊁前庭阵发症(vestibularparoxysmꎬVP)等疾病的诊断标准ꎮ我国也陆续制定出台了MD诊断和治疗指南㊁BPPV诊断和治疗指南㊁眩晕诊治多学科专家共识㊁前庭功能检查专家共识VM诊治专家共识等ꎮ这些前庭疾病的国际分类㊁诊断标准㊁诊疗指南㊁规范以及专家共识的出台ꎬ对提高我国眩晕/头晕疾病的整体诊治水平起到了极大的促进作用ꎮ2㊀前庭功能检查技术进展前庭功能检查是临床上辅助前庭疾病诊断的必要手段ꎬ通过前庭功能检查来对前庭系统的生理功能进行定性㊁定量评估ꎬ明确病变侧别㊁部位[5 ̄6]ꎮ随着前庭功能检查技术的飞速发展ꎬ除了传统的眼震电图㊁旋转试验外ꎬ前庭诱发肌源性电位(vestibu ̄lar ̄evokedmyogenicpotentialꎬVEMP)㊁视频头脉冲检查(videoheadimpulsivetestꎬvHIT)㊁前庭自旋转实验(vestibularautorotationtestꎬVAT)以及主观视觉垂直线检查(subjectivevisualverticalꎬSVV)等也在临床上逐步开展ꎬ能够分别对半规管㊁耳石器㊁前庭神经等进行定性㊁定侧㊁定量的检查ꎮ眼震电图检查包括扫视试验㊁视跟踪试验㊁视动试验㊁凝视试验㊁自发眼震试验㊁冷热试验等ꎬ通过评估视动系统㊁前庭视动系统的功能来反映前庭系统的功能ꎮ外周前庭病变引起的眼震多为水平㊁扭转性眼震ꎬ有疲劳现象ꎬ并被固视抑制ꎻ中枢性眼震则多为粗大㊁非水平性ꎬ如垂直性㊁钟摆型眼震等ꎬ不会被固视抑制ꎬ无疲劳现象ꎮ扫视试验异常多提示为脑干或小脑等中枢系统病变ꎮ视跟踪试验Ⅰ㊁Ⅱ型为正常或外周前庭病变ꎬⅢ㊁Ⅳ型多提示中枢前庭病变ꎮ视动试验异常多提示前庭中枢病变ꎬ也可见于部分外周前庭病变的急性期ꎮ凝视试验中ꎬ中枢病变表现为方向改变的眼震ꎬ而外周前庭病变则表现为方向固定的眼震ꎮ前庭有自身的频率特性ꎬ目前前庭频率的客观检查主要是通过用不同频率刺激半规管壶腹后ꎬ观察和记录眼动情况来判断前庭受损侧别和各半规管的功能ꎮ包括超低频率刺激的温度试验㊁低频的转椅试验以及中高频的VAT和HIT等[5 ̄9]ꎮ温度试验(检测频率0.003~0.008Hz)是通过冷热水或冷热气的灌注ꎬ比较两侧水平半规管的功能ꎬ是临床上评价一侧外周或中枢性前庭功能障碍的常用方法[8]ꎮ在温度试验检查中的眼震极盛期ꎬ进行固视抑制ꎬ如果固视抑制失败ꎬ则提示可能为中枢病变ꎮ旋转试验(检测频率0.01~0.64Hz)通过检查前庭水平半规管系统对一定加速度刺激的反应情况ꎬ定量评价前庭系统功能ꎻvHIT不仅用于检查单侧或双侧水平半规管功能ꎬ还可用于评估垂直半规管的功能状态[9]ꎻVEMP用于检查耳石器功能和中枢病变[10]ꎻSVV是针对椭圆囊病变的主观量化检查[6]ꎮVAT检测频率为0.5~6.0Hzꎬ接近于人体日常活动的频率ꎬ可用于检测水平和垂直方向的高频眼动反射ꎬ通过检测受检者以一定频率主动摆头时的眼动反应ꎬ来评价较高频率的前庭眼动反射(vestibularoculomotorreflexꎬVOR)状况ꎮ临床上通过计算增益㊁相位㊁非对称性等参数来进行分析[6]ꎮ增益降低常见于外周损害ꎬ增高可见于中枢性病变ꎻ外周或中枢病变均可引起相位异常ꎬ增大常提示双侧前庭功能的不对称ꎮvHIT通过检测受检者在快速㊁高频㊁被动头动时的眼动反射来评价前庭功能ꎮ一般认为其代表了较高频率的VORꎬ可反映单个半规管功能状况ꎬ并可分别检查水平㊁垂直半规管中的任意一个ꎬ检测频率为2~5Hzꎮ结合VOR增益值和出现扫视波情况来综合评判半规管功能ꎮ增益反映的是VOR眼动反应与头动反应之间的比值关系ꎬ为眼动与头动的速度比值或眼动曲线与头动曲线下面积比值ꎮ半规管功能受损时表现为VOR增益值降低及延后出现的扫视波ꎬ根据出现的时间分为隐性扫视波和显性扫视波[9]ꎮvHIT异常高度提示外周前庭病变ꎮ目前临床上还有一种头脉冲检查的补充模式 头脉冲抑制试验(suppressionheadimpulseparadigmꎬSHIMP)ꎮ检测方法与传统模式的不同处在于受检者全程凝视随头位同步移动的激光点ꎬ与vHIT检查中出现扫视波是前庭功能障碍的表现不同的是ꎬSHIMP检查中出现的扫视波则是剩余前庭功能的表现[6 ̄7]ꎮ震动诱发眼震试验的检查频率在100Hz左右ꎬ是检测单侧外周前庭功能障碍的有价值的方法ꎬ出现连续5个3ʎ/s以上的眼震为阳性ꎬ常提示双侧前庭功能的不对称[11]ꎮ前庭耳石器对强声或振动刺激会引起相应的肌电反应ꎬ包括球囊诱发的胸锁乳突肌肌源性电位(cervicalVEMPꎬcVEMP)和椭圆囊诱发的眼外肌肌源性电位(ocularVEMPꎬoVEMP)ꎬ分别用于评价球囊与前庭下神经和椭圆囊与前庭上神经通路的功能[10]ꎮ常用的指标是两侧波幅不对称比ꎬ其增大常提示一侧耳石器与前庭上/下神经通路的损伤ꎬ如梅尼埃病㊁前庭神经炎等ꎻ如波幅明显增大或刺激阈值明显降低常见于上半规管裂综合征ꎻ潜伏期延长则多见于迷路后或中枢病变[6ꎬ10]ꎮSVV检查主要用于评价双侧耳石器功能对称性ꎬ偏差一般<3度ꎬ超过此值常提示双侧耳石器功能不对称ꎬ外周或中枢病变均可引起[6]ꎮSVV在鉴别前庭外周与前庭中枢病变方面具有重要意义ꎬ外周前庭病变SVV检查一般偏向患侧ꎬ中枢病变中ꎬ累及低位脑干病变SVV检查偏向患侧ꎬ累及上位脑干则偏向健侧ꎮ需要强调的是ꎬ前庭功能检查技术只是发现问题的手段和方法之一ꎬ因单一前庭功能检查异常并不能明确表示其前庭功能一定存在异常ꎬ常常需要不同检查之间互相印证和补充ꎮ当患者双侧cVEMP都引不出ꎬ并不代表双侧前庭功能一定存在问题ꎬ因为正常人群中亦有部分引不出者ꎬ所以需要其他前庭功能检查来明确该患者是否存在真性前庭功能障碍ꎮ因此ꎬ临床工作中ꎬ医师需要全面了解各种检查技术的适应证范围㊁具备解读检查结果的能力ꎬ才能有针对性地选择合理的检查项目ꎬ根据检查结果并结合病史信息确定临床诊断ꎬ从而精准治疗外周前庭疾病ꎮ3㊀前庭疾病的药物及手术治疗理想情况下ꎬ前庭药物治疗的目标是通过特定和有针对性的分子作用ꎬ显著减轻眩晕症状ꎬ保护或修复病理条件下的前庭感觉网络ꎬ促进前庭代偿ꎬ最终达到提高患者生活质量的目的[12 ̄13]ꎮ但由于前庭疾病的病因和药理学靶点信息的缺乏ꎬ以及不能有效地将药物定向靶向投放等问题ꎬ目前尚无法实现这一理想状态ꎮ目前治疗前庭疾病的药物主要分为前庭抑制药㊁止吐药㊁促进前庭代偿药物ꎬ以及激素㊁扩张血管药物等ꎮ前庭抑制药是减少前庭失衡引起的眼球震颤的药物ꎮ传统的前庭抑制药由三大类药物组成ꎬ即抗胆碱能药㊁抗组胺药和苯二氮类[12 ̄13]ꎮ抗胆碱能药物和抗组胺药是前庭中枢抑制物ꎬ可抑制动物前庭核神经元的放电ꎬ并能降低人类眼球震颤的速度[14]ꎮ但所有常规用于治疗眩晕或运动病的抗胆碱药都有显著的不良反应ꎬ通常包括口干㊁瞳孔扩大和镇静等ꎮ苯二氮类药物是γ氨基丁酸受体(γ ̄aminobutyricacidreceptorꎬGABAR)调节剂ꎬ主要作用是抑制中枢前庭反应[10ꎬ12ꎬ15]ꎮ研究证实小剂量的苯二氮类药物对治疗眩晕非常有用ꎬ也有助于预防运动病[15]ꎬ不良反应主要包括药物依赖㊁记忆受损和跌倒风险增加[13 ̄14]ꎮ无论是抗胆碱能药㊁抗组胺药还是苯二氮类药物ꎬ都会影响前庭损害的代偿ꎬ因此均不适合长期使用ꎮ另外一类用于前庭抑制的药物是钙通道拮抗剂ꎬ最常用的是氟桂利嗪和尼莫地平ꎬ其作用机制是前庭暗细胞也含有钙通道ꎬ钙通道拮抗剂可能通过影响前庭暗细胞内钙通道活动ꎬ改变内淋巴中的离子浓度[16]ꎬ从而发挥抑制前庭的作用ꎮ而且钙通道拮抗剂通常也常具有抗胆碱能和/或抗组胺活性ꎬ如氟桂利嗪[17]ꎮ胃复安㊁异丙嗪㊁昂丹司琼是常用的止吐药物ꎮ止吐药的选择取决于对给药途径和不良反应的考虑ꎮ口服制剂用于轻度恶心ꎻ栓剂常用于因胃无力或呕吐而无法吸收口服药物的门诊患者ꎻ舌下给药㊁注射剂用于急诊室或住院患者ꎮ昂丹司琼是高效的止吐药ꎬ对表现为恶心的前庭障碍者也有效ꎬ但价格昂贵ꎮ虽然这类药物有较好的止吐效果ꎬ但有研究表明这些药物对预防运动病没有帮助[16]ꎮ前庭抑制剂都会影响前庭损伤的代偿ꎬ加速代偿的药物主要是前庭兴奋剂ꎮ倍他司汀是一种H1受体激动剂和H3受体拮抗剂ꎬ可以解除控制组胺释放的负反馈回路ꎬ促进大脑中组胺能神经递质的传递ꎮ也有人认为倍他司汀可能加速前庭代偿ꎬ但也有研究得出结论ꎬ没有足够的证据表明倍他司汀对梅尼埃病是否有影响[18]ꎮ另外一个治疗前庭疾病的药物是银杏叶制剂ꎮ银杏叶可以降低血液黏度ꎬ同时它也可能是一种抗氧化剂ꎮ一项银杏叶与倍他司汀的对照研究结果显示ꎬ银杏叶对眩晕的疗效与倍他司汀相似[19]ꎮ对于前庭疾病的患者ꎬ其具体的药物治疗方案需要针对病因 量身定制 ꎬ比如对于前庭神经炎ꎬ目前只建议短暂使用前庭抑制药ꎻ对于MDꎬ前庭抑制剂无论加或不加止吐药用来治疗急性发作ꎬ这些药物都不能纠正前庭不平衡引起的症状ꎬ只是抑制了失衡的临床表现(如眩晕和恶心)ꎮ而对于预防发作ꎬ通常的做法是建议饮食限盐(1~2g/d)和使用温和的利尿剂ꎬ如氢氯噻嗪ꎮ对于BPPVꎬ物理治疗(手法复位或转椅复位)是最有效的方法[20]ꎬ对复位后有头晕㊁平衡障碍等症状的ꎬ可以给予改善内耳微循环的药物ꎮ对于VMꎬ预防性药物(L ̄型钙通道拮抗剂㊁三环类抗抑郁药㊁β ̄受体阻滞剂)则是治疗该病的主要药物ꎮ对于药物无法控制的MDꎬ可以根据疾病的听力分期和严重程度选择鼓室内注射类固醇激素㊁庆大霉素ꎬ以及手术治疗[21]ꎮ手术包括内淋巴囊手术(减压㊁内淋巴管夹闭)㊁半规管阻塞㊁前庭神经切断㊁迷路切除等ꎮ上半规管裂以及中耳胆脂瘤引起的迷路瘘管的治疗也是以手术为主ꎬ上半规管裂手术包括经乳突径路㊁颅中窝径路的半规管修补术以及经鼓室的圆窗加固术ꎮ听神经瘤引起的眩晕也往往需要手术治疗ꎬ根据肿瘤大小和听力情况等可以选择经迷路径路㊁乙状窦后径路以及颅中窝径路等ꎮ小的局限于内听道内而且无实用听力者也可在耳内镜下经耳蜗手术切除ꎮ双侧前庭病目前缺乏有效药物治疗ꎬ物理治疗效果也不甚理想ꎬ目前最有前景的治疗手段可能是前庭植入[22]ꎮ日内瓦Maastrichtgroup的一项研究中ꎬ为13例双侧前庭功能低下的患者成功安装了前庭植入物ꎬ并开发了一种将运动传感器与系统耦合的特殊接口ꎬ以捕捉来自三轴陀螺仪的信号ꎬ并调制 基线电活动 ꎮ前庭植入可行性所需的最后一个里程碑是证明人工恢复的前庭反射足以减轻患者的症状ꎬ尤其是频繁出现的振动幻视ꎮ2016年ꎬGuinand等[23]测量了6例前庭植入患者的动/静态视力ꎬ在没有前庭植入物的情况下ꎬ他们的视力在动态条件下受损ꎬ而当前庭植入物打开时ꎬ视力恢复正常ꎮ鉴于这些令人鼓舞的研究成果ꎬ人工前庭植入可能在不久的将来就能够进入临床应用ꎮ4㊀前庭康复前庭康复治疗(vestibularrehabilitationtherapyꎬVRT)已经有超过70年的历史ꎬ是一项以运动为基础的系统训练方式ꎬ通过中枢代偿ꎬ前庭康复能够改善不平衡㊁跌倒㊁头晕㊁眩晕㊁运动敏感等前庭症状和恶心㊁焦虑等伴随症状ꎮ越来越多的证据支持前庭障碍患者进行前庭康复治疗ꎬ而目前已经涌现了很多更有效的干预措施ꎮ比如前庭康复的辅助设施㊁可穿戴的前庭康复辅助设备以及结合虚拟现实技术的前庭康复训练等[24 ̄26]ꎮ自20世纪90年代末以来ꎬ有关前庭病变患者治疗技术的证据显著增加ꎬ使得干预措施变得更加精细和有效ꎮ具有相似诊断的患者的身体表现和功能局限性通常会大不相同ꎮ尽管大多数VRT运动项目利用眼睛和头部运动ꎬ但运动类型及其处方是个性化的ꎬ针对的是患者的缺陷和症状ꎬ而不是针对特定的诊断ꎮ症状主诉可能包括不平衡(静态姿势和步态ꎬ尤其是与头部运动相关的)㊁跌倒和害怕跌倒㊁视力下降㊁头晕㊁焦虑㊁恶心㊁眩晕和运动敏感性ꎮ针对前庭损伤和功能受限的前庭康复技术是基于前庭适应㊁习服㊁感觉替代等多种机制发展而来的ꎬ前庭康复的练习方法包括促进凝视稳定练习㊁锻炼习服症状㊁练习改善平衡㊁步态及耐力等[27 ̄28]ꎮ适应训练或视觉 ̄前庭相互作用练习通过反复的前庭刺激(如头部运动)ꎬ以促进残余前庭系统的适应ꎮ适应性训练对治疗凝视不稳是有效的ꎬ也被证明可以改善平衡和减少头晕ꎮ习服训练则利用反复暴露于诱发症状的刺激来减少姿势变化引起的头晕ꎮ随着时间的推移ꎬ系统地暴露于轻微的㊁暂时的刺激后ꎬ头晕会逐渐减轻ꎬ可适用于没有明确诊断㊁但具有良性病因的位置性眩晕患者ꎬ治疗的主要目标是改善眩晕症状ꎬ对快速运动导致的异常前庭反应习服化ꎮ替代练习是利用其他感官刺激ꎬ如视觉或本体觉来替代前庭功能的缺失或下降ꎬ从而加强姿势控制和减少跌倒ꎮ该策略对双侧前庭功能减退和多感觉不平衡的患者尤其有效ꎮ在传统前庭康复技术基础上ꎬ近年来的一些新技术也逐渐应用到前庭功能障碍患者的康复治疗中ꎬ比如利用振动触觉和听觉反馈来增强平衡功能ꎬ以及虚拟现实技术在前庭康复中的应用等ꎮ研究发现ꎬ老年人和前庭障碍患者在家中利用振动触觉反馈练习可改善其平衡功能[29]ꎮ虚拟现实或其他使用沉浸式环境模拟的视动训练平衡也越来越多地应用于前庭康复训练中ꎬ也取得了良好的效果[30 ̄31]ꎬ而且相对于传统的前庭康复ꎬ多数患者报告说他们更喜欢虚拟训练[32]ꎮ随着游戏产业的发展ꎬ已开发出低成本的虚拟现实系统ꎬ如任天堂WiiFitPlusꎬ该系统还能够在平衡游戏期间向屏幕提供视觉反馈[33]ꎮ鉴于这是一种可以在家里进行的令人愉快的运动方式ꎬ市场上的Wii ̄Fit或其他较新的低成本虚拟现实设备可能是居家进行前庭康复训练的有用工具ꎮ当然ꎬ还需要进一步的相关研究来验证这些设备的训练效果ꎮ前庭康复运动对外周前庭功能障碍的疗效可靠ꎬ定制化的治疗方案侧重于减少头晕㊁振动幻视和姿势不稳的症状ꎬ并解决患者的功能缺陷ꎮ运动的目的是促进前庭功能障碍的中枢代偿ꎮ单侧前庭功能障碍患者往往表现良好ꎬ通常可以恢复全部或大部分日常生活活动ꎬ但双侧前庭功能丧失的患者仍然存在平衡障碍ꎮ对于双侧前庭病患者来说ꎬ人工前庭植入可能是最有效的治疗方式ꎮ前庭康复技术在过去几十年中不断发展ꎬ但国内前庭康复起步较晚ꎬ相关研究与国外差距较大ꎬ需要进一步重视[34]ꎮ5㊀结㊀语随着前庭生理研究的深入㊁前庭功能检查技术的不断发展和完善ꎬ以及各相关学科的重视和不断努力ꎬ对前庭疾病的认识不断深入ꎬ诊治水平不断提高ꎮ前庭疾病的精准诊治ꎬ除了进行准确的病因诊断外ꎬ还要兼顾症状控制㊁生活质量改善ꎬ要结合患者的个体差异ꎬ精准选择合适的治疗方式ꎬ综合药物治疗㊁手术治疗以及VRT等ꎮ需要在准确病因诊断的前提下ꎬ选择最适合的个体化治疗ꎬ以达到更好的症状控制㊁更好的生活质量ꎮ参考文献:[1]WaltherLE.Currentdiagnosticproceduresfordiagnosingvertigoanddizziness[J].GMSCurrTopOtorhinolaryn ̄golHeadNeckSurgꎬ2017ꎬ18(16):Doc02.doi:10.3205/cto000141.[2]StruppMꎬMandalàMꎬLópez ̄EscámezJA.Peripheralvestibulardisorders[J].CurrOpinNeurolꎬ2019ꎬ32(1):165 ̄173.doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000649. [3]WorldHealthOrganizationꎬInternationalClassificationofDiseasesꎬ11theditionꎬhttps://icd.who.int/browse11/l ̄m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1300772836. [4]BisdorffARꎬStaabJPꎬNewman ̄TokerDE.Overviewoftheinternationalclassificationofvestibulardisorders[J].NeurolClinꎬ2015ꎬ33(3):541 ̄50ꎬvii.doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.010.[5]中国医药教育协会眩晕专业委员会ꎬ中国康复医学会眩晕与康复专业委员会ꎬ中西医结合学会眩晕专业委员会ꎬ等.前庭功能检查专家共识(一)(2019)[J].中华耳科学杂志ꎬ2019ꎬ17(1):117 ̄123.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672 ̄2922.2019.01.020.[6]中国医药教育协会眩晕专业委员会ꎬ中国康复医学会眩晕与康复专业委员会ꎬ中西医结合学会眩晕专业委员会ꎬ等.前庭功能检查专家共识(二)(2019)[J].中华耳科学杂志ꎬ2019ꎬ17(2):144 ̄149.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672 ̄2922.2019.02.002.[7]MacDougallHGꎬMcGarvieLAꎬHalmagyiGMꎬetal.Anewsaccadicindicatorofperipheralvestibularfunctionbasedonthevideoheadimpulsetest[J].Neurologyꎬ2016ꎬ87(4):410 ̄418.doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000002827. [8]ShepardNTꎬJacobsonGP.Thecaloricirrigationtest[M]//HandbookofClinicalNeurology.Amsterdam:Elsevierꎬ2016:119 ̄131.doi:10.1016/b978 ̄0 ̄444 ̄63437 ̄5.00009 ̄1.[9]AlhabibSFꎬSalibaI.Videoheadimpulsetest:areviewoftheliterature[J].EurArchOtorhinolaryngolꎬ2017ꎬ274(3):1215 ̄1222.doi:10.1007/s00405 ̄016 ̄4157 ̄4. [10]RosengrenSMꎬColebatchJGꎬYoungASꎬetal.Vestib ̄ularevokedmyogenicpotentialsinpractice:Methodsꎬpitfallsandclinicalapplications[J].ClinNeurophysiolPractꎬ2019ꎬ4:47 ̄68.doi:10.1016/j.cnp.2019.01.005. [11]ZamoraEGꎬAraújoPEꎬGuillénVPꎬetal.Parametersofskullvibration ̄inducednystagmusinnormalsubjects[J].EurArchOtorhinolaryngolꎬ2018ꎬ275(8):1955 ̄1961.doi:10.1007/s00405 ̄018 ̄5020 ̄6.[12]ChabbertC.Principlesofvestibularpharmacotherapy[M]//HandbookofClinicalNeurology.Amsterdam:Elsevierꎬ2016:207 ̄218.doi:10.1016/b978 ̄0 ̄444 ̄63437 ̄5.00014 ̄5.[13]StruppMꎬKremmydaOꎬBrandtT.Pharmacotherapyofvestibulardisordersandnystagmus[J].SeminNeurolꎬ2013ꎬ33(3):286 ̄296.doi:10.1055/s ̄0033 ̄1354594. [14]SotoEꎬVegaR.Neuropharmacologyofvestibularsys ̄temdisorders[J].CurrNeuropharmacolꎬ2010ꎬ8(1):26 ̄40.doi:10.2174/157015910790909511.[15]HuppertDꎬStruppMꎬMückterHꎬetal.Whichmedica ̄tiondoIneedtomanagedizzypatients?[J].ActaOto ̄laryngolꎬ2011ꎬ131(3):228 ̄241.doi:10.3109/00016489.2010.531052.[16]HainTCꎬUddinM.PharmacologicaltreatmentofVertigo[J].CNSDrugsꎬ2003ꎬ17(2):85 ̄100.doi:10.2165/00023210 ̄200317020 ̄00002.[17]LepchaAꎬAmalanathanSꎬAugustineAMꎬetal.Fluna ̄rizineintheprophylaxisofmigrainousvertigo:aran ̄domizedcontrolledtrial[J].EurArchOtorhinolaryngolꎬ2014ꎬ271(11):2931 ̄2936.doi:10.1007/s00405 ̄013 ̄2786 ̄4.[18]RamosAlcocerRꎬLedezmaRodríguezJGꎬNavasRomeroAꎬetal.UseofbetahistineinthetreatmentofperipheralVertigo[J].ActaOtolaryngolꎬ2015ꎬ135(12):1205 ̄1211.doi:10.3109/00016489.2015.1072873. [19]SokolovaLꎬHoerrRꎬMishchenkoT.Treatmentofver ̄tigo:arandomizedꎬdouble ̄blindtrialcomparingeffica ̄cyandsafetyofGinkgobilobaextractEGb761andbeta ̄histine[J].IntJOtolaryngolꎬ2014ꎬ2014:682439.doi:10.1155/2014/682439.[20]陈太生ꎬ王巍ꎬ徐开旭ꎬ等.良性阵发性位置性眩晕及其诊断治疗的思考[J].山东大学耳鼻喉眼学报ꎬ2019ꎬ33(5):1 ̄5.doi:10.6040/j.issn.1673 ̄3770.1.2019.053.CHENTaishengꎬWANGWeiꎬXUKaixuꎬetal.ThoughtsonbenignparoxysmalpositionalVertigoanditsdiagnosisandtreatment[J].JournalofOtolaryngologyandOphthalmologyofShandongUniversityꎬ2019ꎬ33(5):1 ̄5.doi:10.6040/j.issn.1673 ̄3770.1.2019.053. [21]LiuYPꎬYangJꎬDuanML.CurrentstatusonresearchesofMeniere̓sdisease:areview[J].ActaOtolaryngolꎬ2020ꎬ140(10):808 ̄812.doi:10.1080/00016489.2020.1776385.[22]GuyotJPꎬPerezFornosA.Milestonesinthedevelopmentofavestibularimplant[J].CurrOpinNeurolꎬ2019ꎬ32(1):145 ̄153.doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000639. [23]GuinandNꎬvandeBergRꎬCavuscensSꎬetal.Thevideoheadimpulsetesttoassesstheefficacyofvestibu ̄larimplantsinhumans[J].FrontNeurolꎬ2017ꎬ8:600.doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00600.[24]SulwaySꎬWhitneySL.Advancesinvestibularrehabili ̄tation[J].AdvOtorhinolaryngolꎬ2019ꎬ82:164 ̄169.doi:10.1159/000490285.[25]DunlapPMꎬHolmbergJMꎬWhitneySL.Vestibularrehabilitation:advancesinperipheralandcentralvestibu ̄lardisorders[J].CurrOpinNeurolꎬ2019ꎬ32(1):137 ̄144.doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000632.[26]MeldrumDꎬJahnK.Gazestabilisationexercisesinves ̄tibularrehabilitation:reviewoftheevidenceandrecentclinicaladvances[J].JNeurolꎬ2019ꎬ266(suppl1):11 ̄18.doi:10.1007/s00415 ̄019 ̄09459 ̄x.[27]HallCDꎬHerdmanSJꎬWhitneySLꎬetal.Vestibularrehabilitationforperipheralvestibularhypofunction:anevidence ̄basedclinicalpracticeguideline:FROMTHEAMERICANPHYSICALTHERAPYASSOCIATIONNEUROLOGYSECTION[J].JNeurolPhysTherꎬ2016ꎬ40(2):124 ̄155.doi:10.1097/npt.0000000000000120. [28]KlattBNꎬCarenderWJꎬLinCCꎬetal.Aconceptualframeworkfortheprogressionofbalanceexercisesinpersonswithbalanceandvestibulardisorders[J].PhysMedRehabilIntꎬ2015ꎬ2(4):1044.[29]AllumJHJꎬHoneggerF.Vibro ̄tactileandauditorybal ̄ancebiofeedbackchangesmuscleactivitypatterns:possi ̄bleimplicationsforvestibularimplants[J].JVestibResꎬ2017ꎬ27(1):77 ̄87.doi:10.3233/ves ̄170601. [30]PavlouMꎬKanegaonkarRGꎬSwappDꎬetal.TheeffectofvirtualrealityonvisualVertigosymptomsinpatientswithperipheralvestibulardysfunction:apilotstudy[J].JVestibResꎬ2012ꎬ22(5ꎬ6):273 ̄281.doi:10.3233/ves ̄120462.[31]AlahmariKAꎬSpartoPJꎬMarchettiGFꎬetal.Compari ̄sonofvirtualrealitybasedtherapywithcustomizedves ̄tibularphysicaltherapyforthetreatmentofvestibulardis ̄orders[J].IEEETransNeuralSystRehabilEngꎬ2014ꎬ22(2):389 ̄399.doi:10.1109/tnsre.2013.2294904. [32]MeldrumDꎬHerdmanSꎬVanceRꎬetal.Effectivenessofconventionalversusvirtualreality ̄basedbalanceexer ̄cisesinvestibularrehabilitationforunilateralperipheralvestibularloss:resultsofarandomizedcontrolledtrial[J].ArchPhysMedRehabilitationꎬ2015ꎬ96(7):1319 ̄1328.e1.doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.032.[33]ClarkRAꎬBryantALꎬPuaYHꎬetal.Validityandreli ̄abilityoftheNintendoWiiBalanceBoardforassessmentofstandingbalance[J].GaitPostureꎬ2010ꎬ31(3):307 ̄310.doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.11.012. [34]杨军ꎬ郑贵亮.进一步重视前庭康复[J].临床耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志ꎬ2019ꎬ33(3):204 ̄206.doi:10.13201/j.issn.1001 ̄1781.2019.03.004.YANGJunꎬZHENGGuiliang.Furtheremphasisonves ̄tibularrehabilitation[J].JournalofClinicalOtorhinolar ̄yngologyHeadandNeckSurgeryꎬ2019ꎬ33(3):204 ̄206.doi:10.13201/j.issn.1001 ̄1781.2019.03.004.(编辑:李纬)。

颞下颌关节紊乱病与身体姿势的相关性研究进展

• 368 •口腔医学2022年4月第42卷第4期颞下颌关节紊乱病与身体姿势的相关性研究进展金春晓、杨霖2,刘洋3,李晓菁余丽霞3,高姗姗1[摘要]众多研究表明颞下颌关节紊乱病与人站立时的身体姿势有密切的关系。本文从颞下颌关节紊乱病与静态身体姿势 的相互关系及作用机制两个方面进行综述,以期从身体姿势角度对TMD的防治提供一定的参考。[关键词]颞下颌关节紊乱病;身体姿势;治疗;病因[中图分类号]R782.6 [文献标识码]A [文章编号]1003-9872(2022)04-0368-05[doi] 10.13591/j.cnki.kqyx.2022.04.017

Relationship between temporomandibular joint disorder and body postureJIN Chunxiao, YANG Lin, LIU Yang^ LI Xiaojing, YU Lixia, GAO Shansh an. (State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Dept, of Prosthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology ^ Sichuan University^ Chengdu 610041, China)Abstract : Many studies have shown that temporomandibular joint disorder(TMD) is closely related to body posture. This paper re

views the relationship between TMD and body posture and its mechanism, in order to provide reference for the prevention and treatment of TMD from the perspective of body posture.Key words: temporomandibular joint disorder; body posture; therapy; etiology

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

CervicalSpineDysfunctionsinPatientsWithChronicSubjectiveTinnitus

*†SarahMichiels,*WillemDeHertogh,*‡StevenTruijen,and†‡§PaulVandeHeyning

*DepartmentofRehabilitationSciencesandPhysiotherapy,FacultyofMedicineandHealthSciences,UniversityofAntwerp,Antwerp,Belgium;ÞDepartmentofOtorhinolaryngology,AntwerpUniversityHospital,Edegem,Belgium;þMultidisciplinaryMotorCentreAntwerp,UniversityofAntwerp,Antwerp,Belgium;and§DepartmentofTranslationalNeurosciences,FacultyofMedicineandHealthSciences,UniversityofAntwerp,Antwerp,Belgium

Objective:Toassess,characterize,andquantifycervicalspinedysfunctioninpatientswithcervicogenicsomatictinnitus(CST)comparedtopatientssufferingfromotherformsofchronicsub-jectivenon-pulsatiletinnitus.StudyDesign:Cross-sectionalstudy.Setting:Tertiaryreferralcenter.Patients:Consecutiveadultpatientssufferingfromchronicsubjectivenon-pulsatiletinnituswereincluded.Exclusioncriteria:Me´nie`re’sdisease,middleearpathology,intracranialpathology,cervicalspinesurgery,whiplashtrauma,temporomandibulardysfunction.Intervention:Assessmentcomprisesmedicalhistory,ENTex-aminationwithmicro-otoscopy,audiometry,tinnitusassessment,temporomandibularandcervicalspineinvestigation,andbrainMRI.PatientswereclassifiedintoCSTandnon-CSTpopulation.CervicalspinedysfunctionwasinvestigatedusingtheNeckBournemouthQuestionnaire(NBQ)andclinicaltestsofthecer-vicalspine,containingrangeofmotion,painprovocation(adaptedSpurlingtest,AST),andmuscletests(tendernessviatriggerpoints,strengthandenduranceofdeepneckflexors).

MainOutcomeMeasures:Between-groupanalysiswasper-formed.Theprevalenceofcervicalspinedysfunctionwasde-scribedforthetotalgroupandforCSTandnon-CSTgroups.Results:Intotal,87patientswereincluded,ofwhich37(43%)werediagnosedwithCST.Incomparisonwiththenon-CSTgroup,theCSTgroupdemonstratedasignificantlyhigherprev-alenceofcervicalspinedysfunction.IntheCSTgroup,68%hadapositivemanualrotationtest,47%apositiveAST,49%apositivescoreonboth,and81%hadpositivetriggerpoints.Inthenon-CSTgroup,thesepercentageswere36,18,10,and50%,respectively.Furthermore,79%oftheCSTgrouphadapositiveNBQversus40%inthenon-CSTgroup.Significantdifferencesbetweenthebothgroupswerefoundforalltheaforementionedvariables(allpG0.005).Conclusions:Althoughahigherprevalenceofneckdys-functionwasfoundintheCSTgroup,neckdysfunctionisofteninnon-CSTpatients.KeyWords:CervicalspinedysfunctionsVTinnitus.

OtolNeurotol36:741Y745,2015.

Tinnitusisthephantomsensationofsound,intheab-senceofovertacousticstimulation(1).Itoccursin10to15%oftheadultpopulation(2).Tinnituscanberelatedtomanydifferentetiologiessuchashearinglossoranoisetrauma.Withinthegroupofpatientssufferingfromchronicsubjectivenon-pulsatiletinnitus,asubgroupcanbedefinedwherethetinnitusisrelatedtothesomatosensorysystemofthe

cervicalspine(2).Thistypeoftinnitusisnamedcervi-cogenicsomatictinnitus(CST).TheexistenceofCSTissupportedbyseveralanimalstudies,whichhavefoundconnectionsbetweenthecer-vicalsomatosensorysystemandthecochlearnuclei(CN)(3,4).Cervicalsomatosensoryinformationisconveyedbyafferentfibers,thecellbodiesofwhicharelocatedinthedorsalrootgangliaorthetrigeminalganglion,tothebrain.Theseafferentfibersalsoprojecttotheauditorysystem.Thismakesthesomatosensorysystemabletoinfluencetheauditorysystembyalteringthespontaneousrates(i.e.,notdrivenbyauditorystimuli)orthesynchronyoffiringamongneuronsintheCN,inferiorcolliculus,orauditorycortex.Inthisway,thesomatosensorysystemisabletoaltertheintensityandthecharacterofthetinnitus(5).

AddresscorrespondenceandreprintrequeststoSarahMichiels,Wilrijkstraat10,2650Edegem,Belgium;E-mail:sarah.michiels@uantwerpen.beTheauthorsdisclosenoconflictsofinterest.

Otology&Neurotology36:741Y745Ó2014,Otology&Neurotology,Inc.

741Copyright © 2015 Otology & Neurotology, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.Althoughanimalstudieshavedemonstratedtheexis-tenceofneuralconnectionsthatcancauseCST,thediag-nosisischallengingandismainlybasedonmedicalhistory.ThediagnosisofCSTisbasedonthediagnosticcriteriaforsomatictinnitus(6).TheprimarilyuseddiagnosticcriterionforCSTisthetemporalcoincidenceofonsetorincreaseofbothneckpainandtinnitus.CSTislinkedtomyofascialdysfunctionintheheadandneckregioncomprisingcervicaldysfunction.Todate,however,itisunclearwhichstructuresofthecer-vicalspineareaffectedinpatientswithCST,andnoin-formationisavailableonthepresenceofcervicalspinedysfunctioninnon-CSTpatients.Therefore,theaimofthisstudyistoassess,characterize,andquantifycervicalspinedysfunctioninpatientsdiag-nosedwithCSTincomparisonwithpatientssufferingfromotherformsofchronicsubjectivenon-pulsatiletinnitus.