英语报刊选读 读者文摘原文版INSPIRING STORIES (3)

英美报刊文章阅读精选本第五版课文翻译

Lesson4 Is an Ivy League Diploma Worth It?花钱读常春藤名校值不值?1.如果愿意的话,施瓦茨(Daniel Schwartz)本来是可以去一所常春藤联盟(Ivy League)院校读书的。

他只是认为不值。

2.18 岁的施瓦茨被康奈尔大学(Cornell University)录取了,但他最终却去了纽约市立大学麦考利荣誉学院(City University of New York’s Macaulay Honors College),后者是免费的。

3.施瓦茨说,加上奖学金和贷款的支持,家里原本是可以付得起康奈尔的学费的。

但他想当医生,他觉得医学院是更有价值的一项投资。

私立学校医学院一年的花费动辄就要4 万5 美元。

他说,不值得为了一个本科文凭一年花5 万多美元。

4.助学贷款违约率日益攀升,大量的大学毕业生找不到工作,因此越来越多的学生认定,从一所学费不太贵的学校拿到的学位和从一所精英学校拿到的文凭没什么区别,并且不必背负贷款负担。

5.Robert Pizzo 越来越多的学生选择收费较低的公立大学,或选择住在家里走读以节省住房开支。

美国学生贷款行销协会(Sallie Mae)的一份报告显示,2010 年至2011 学年,家庭年收入10 万美元以上的学生中有近25%选择就读两年制的公立学校,高于上一学年12%的比例。

6.这份报告称,这样的选择意味着,在2010 至2011 学年,各个收入阶层的家庭在大学教育上的花费比上一年少9%,平均支出为21,889 美元,包括现金、贷款、奖学金等。

高收入家庭的大学教育支出降低了18%,平均为25,760 美元。

这份一年一度的报告是在对约1,600 名学生和家长进行问卷调查后完成的。

7.这种做法是有风险的。

顶级大学往往能吸引到那些已经不再去其他学校招聘的公司前来招聘。

在许多招聘者以及研究生院看来,精英学校的文凭还是更有吸引力的。

英美报刊选读_passage_13_the_decline_of_neatness_(含翻译)111

The Decline of Neatness 行为标准的蜕化By Norman CousinsAnyone with a passion for hanging labels on people or things should have little difficulty in recognizing that an apt tag for our time is the “Unkempt Generation”. 任何一个喜欢给别人或事物贴标签的人应该不难发现我们这个时代合适的标签是“邋遢的一代”。

I am not referring solely to college kids. The sloppiness virus has spread to all sectors of society," People go to all sorts of trouble and expense to look uncombed, unshaved. unpressed.3 我说这话不仅仅是针对大学生。

邋遢这种病毒已经蔓延到社会各个部分。

人们刻意呈现一幅蓬头散发、边幅不修、衣着不整的形象。

The symbol of the times is blue jeans—not just blue jeans in good condition but jeans that are frayed, torn, discolored. They don't get that way naturally. No one wants blue jeans that are crisply clean or spanking new. 如今时代潮流的象征是穿蓝色牛仔裤--不是完好的牛仔裤,而是打磨过的,撕裂开的,和褪色了的牛仔裤。

正常穿着磨损很难达到上述效果。

没有人喜欢穿干净崭新的牛仔裤。

Manufacturers recognize a big market when they see it, and they compete with one another to offer jeans(that are made to look as though they've just been discarded by clumsy house painters after ten years of wear. )生产商意识到这将是个潜力巨大的市场,于是展开了激烈地竞争,生产出的牛仔裤好像是笨拙的油漆工人穿了十年之后扔掉的一样。

美英报刊阅读教程Lesson 35 课文

Lesson 35 Spamming the Worldby BY BRAD STONE AND JENNIFER LIN | NEWSWEEKFrom the magazine issue dated Aug 19, 2002In A Popularity Contest, …Bulk E-Mailers‟ Would Rank Just Above Child Pornographers. But The Scourge Of The Internet Is Defending Its Vocation.1. Al Ralsky would like you to have thick, lustrous hair. He also wants to help you buy a cheap car, get a loan regardless of your credit history and earn a six-figure income from the comfort of your home. But according to his critics, Ralsky‟s no t a do-gooder, but a bane of the Internet–a spammer, responsible for deluging e-mail accounts and choking the Internet service providers (ISPs) that administer them. In real life, the 57-year-old father of three lives in a middle-class suburb of Detroit. He started bulk e-mailing seven years ago, when he was flat broke. To buy his first two computer servers, he had to sell his 1994 Toyota Camry. These days Ralsky sends out more than 30 million e-mails a day and raves about the possibilities of marketing on the Internet. “It‟s the most fair playing field in the world,” he says. “It makes you equal with any Fortune 500 company.”2. In a popularity contest among Net users, spammers would probably rank only slightly above child pornographers. Spam–unsolicited messages that make their way to your e-mail inbox with misleading subject lines and dubious propositions (from pyramid schemes to porno come-ons)–accounts for 30 to 50 percent of all e-mail traffic on the Net. Users are fed up, and big ISPs like AOL and Earthlink, increasingly overwhelmed by the excess traffic, are taking some spam operators to court. Meanwhile, vigilante anti-spam organizations like SpamCop are aggressively blacklisting spam operators and publishing their home and family information on the Web. Anti-spam sentiment has even evolved to the point where spammers themselves are feeling like victims, and are defending what they call an honest, legal living. Maryland e-mailer Alan Moore, also known as “Dr. Fat” for his herbal weight-loss pills, says spammers are “helping the economy and adding to the GNP. People need to realize his.”3. Spam operations are often, by necessity, fly-by-night businesses. Bulk e-mailers gather addresses using “spambots” like the $179 Atomic Harvester, a piece of software that scours the Internet 24/7, vacuuming up addresses it encounters on bulletin boards and directories. Spammers often don‟t charge clients anything up front, but will take 40 to 50 percent of the revenue an ad generates (or, with products like insurance, $7 a lead). Since most U.S. ISPs have policies that prohibit sending out spam, the majority of spammers operate by sending their messages to “blind” relays, computers in China, South Korea or Taiwan that redirect the e-mail and make it difficult to trace.4. Recently, life has become more onerous for bulk e-mailers. Companies and ISPs are using new software to identify and stop spam as it comes into the network, before it gets distributed to individual inboxes. (This is why spam subject lines are now misleadingly banal or end in numbers: to trick the software, not you.) And with so many more marketing messages clogging Net accounts, users are increasingly inclined to hit the delete button when they see a piece of spam. One bulk e-mailer says that when she started spamming in 1999, she could send out 100,000 e-mails and get 25 responses. Today, she has to send out a million messages to get the same response (a .0025 percent hit rate).5. While most spammers claim they‟ve made hundreds of thousands–some even say millions–of dollars in past years by taking big cuts of their clients‟ revenue, they‟re tight-lipped about their current income. founder Steve Linford, whose anti-spam agents snoop on the e-mailers‟ private online forums to stay on top of trends in the business, says there‟s good reason: “We know they hardly make anything because they‟re always complaining about it.” Several spam operations are also being threatened by litigation. For example, Al Ralsky has been sued in Virginia state court for allegedly sending millions of messages in mid-2000 that crashed the servers of Verizon Online. (His lawyer denies the charges.) The trial is set for this fall, but the judge in the Ralsky case has already ruled a spammer can be held liable in any state where his messages are received.6. In a world where every niche industry speaks loudly to defend its interests, perhaps it‟s not surprising that spammers are joining forces and trying to fight back. Thirty prolific e-mailers recently banded together in something called the Global E-mail Marketing Association (GEMA). The director, a southern California-based e-mailer who would like to be called “Tara,” says the purpose of GEMA is to regulate the industry and ensure its members abide by certain rules, such as allowing recipients to opt out of any list. She also wants to improve the public‟s perception of spamming. First step: changing the name. “We are …commercial bulk e-mailers‟, not spammers,” she says. “I would appreciate if NEWSWEEK would at least give us the dignity of that.”7. Ronnie Scelson is another spammer showing defiance in the face of distaste for his profession. The 28-year-old father of three from Slidell, La., dropped out of high school in the ninth grade but says he‟s made millions sending o ut 560 million e-mail messages a week, hawking everything from travel deals to lingerie. As a result, he drives a 2001 Corvette, and recently bought a five-bedroom home with a game room and pool. In May, the company Scelson founded, Opt-In Marketing, turned the tables and sued two ISPs and three anti-spam organizations in Civil District Court in New Orleans. The suit alleges that the ISPs, New Jersey-based CoVista and its Denver-based backbone provider Qwest, cut off his Internet access and denied his free-speech rights.8. Scelson draws a distinction between his old profession, spamming, and his new one, bulk e-mailing: he says he currently allows people to take themselves off his lists and uses American ISPs to send e-mail instead of foreign relays. But spam is in the eye of the beholder, and recently one of his high-speed Internet lines was temporarily blocked by his new ISP. Now Scelson wonders aloud if playing by the rules is even worth it and threatens to return to his old ways. “I‟m going back to spamm ing. I don‟t care if I have to relay, work through a proxy or spoof an IP address, I‟ll do it.”9. Anti-spammers practically leak venom when it comes to addressing the bid for dignity made by their rivals. Julian Haight, the founder of SpamCop, says spamme rs deserve “every ounce of the image that they have… The correlation between spamming and rip-off deals is unreal.” Verizon exec Tom Daly says spam is insidious because it shifts the costs and burden of handling massive volumes of mail to the network providers. And Internet users: well, no one is exactly clamoring for more e-mail about get-rich-quick schemes or magical ways to enhance their you-know-what. For spammers (er, commercial bulk e-mailers), the quickest route to respectability may be to find another line of work altogether.Find this article at/id/65418。

英语报刊选读 读者文摘原文版INSPIRING STORIES (4)

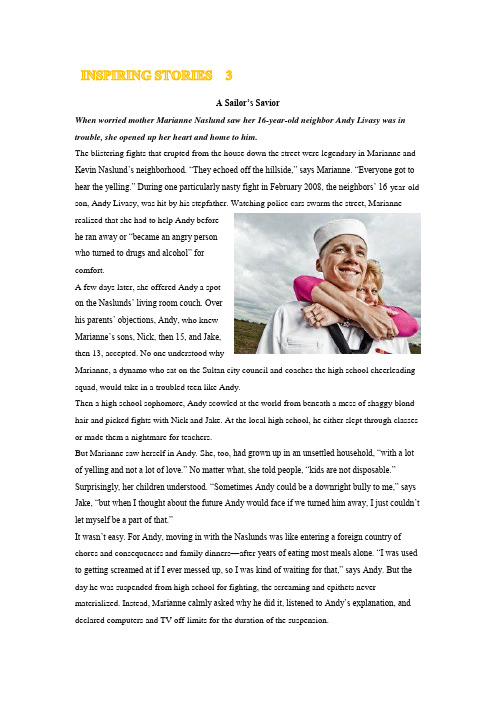

A Sailor’s SaviorWhen worried mother Marianne Naslund saw her 16-year-old neighbor Andy Livasy was in trouble, she opened up her heart and home to him.The blistering fights that erupted from the house down the street were legendary in Marianne and Kevin Naslund’s neighborhood. “They echoed off the hillside,” says Marianne. “Everyone got to hear the yelling.” During one particularly nasty fight in February 2008, the neighbors’ 16-year-old son, Andy Livasy, was hit by his stepfather. Watching police cars swarm the street, Marianne realized that she had to help Andy beforehe ran away or “became an angry personwho turned to drugs and alcohol” forcomfort.A few days later, she offered Andy a spoton the Naslunds’ living room couch. Overhis parents’ objections, Andy, who knewMarianne’s sons, Nick, then 15, and Jake,then 13, accepted. No one understood whyMarianne, a dynamo who sat on the Sultan city council and coaches the high school cheerleading squad, would take in a troubled teen like Andy.Then a high school sophomore, Andy scowled at the world from beneath a mess of shaggy blond hair and picked fights with Nick and Jake. At the local high school, he either slept through classes or made them a nightmare for teachers.But Marianne saw herself in Andy. She, too, had grown up in an unsettled household, “with a lot of yelling and not a lot of love.” No matter what, she told people, “kids are not disposable.” Surprisingly, her children understood. “Sometimes Andy could be a downright bully to me,” says Jake, “but when I thought about the future Andy would face if we turned him away, I just couldn’t let myself be a part of that.”It wasn’t easy. For Andy, moving in with the Naslunds was like entering a foreign country of chores and consequences and family dinners—after years of eating most meals alone. “I was used to getting screamed at if I ever messed up, so I was kind of waiting for that,” says Andy. But the day he was suspended from high school for fighting, the screaming and epithets never materialized. Instead, Ma rianne calmly asked why he did it, listened to Andy’s explanation, and declared computers and TV off-limits for the duration of the suspension.“Marianne did it so that instead of fearing a punishment, I didn’t want to let her down,” says Andy. “I didn’t get into another fight for the rest of high school.”With his biological family, Andy had yelled himself into regular migraines. With the Naslunds, his headaches disappeared, along with most of his angry meltdowns. After six months, he asked Kevin to cut his hair. Two years later, he volunteered to coach youth soccer. And though few adults expected it from the boy with the grade-F mouth, in 2010 he graduated on time from Sultan’s alternative high school.“If I hadn’t moved in with the Naslunds, I probably would have dropped out,” Andy says.After four years, Marianne calls Andy her third son, and “if someone asks about my family, I say that he’s one of my brothers,” says Jake. Andy has had no contact with his mom and stepdad since moving out, even though they still live in the neighborhood and say they’re pleased with how their son has turned out. And Andy, who recently joined the Navy, at age 19, knows where he’s heading when he comes home on leave.Says Andy, “What were the chances of my living across the st reet from someone who had a similar childhood, like Marianne, who would take me in and explain, ‘You can change your life around’?”How a Rwandan Teen Overcame a Legacy of GenocideFar from home, in a war-torn land, a charity worker met a child who had every reason to hate—and yet taught volumes about love.He works with the energy and intensity, if not the skill, of a mechanic twice his age. He keeps his head down, focusing on his task, talking to himself—threading greased pedals onto one of 120 sturdy b lack bikes we’re here to build and donate to a Rwandan charity so people can ride to work, to school, to a well with clean water. He looks to be the same age as my third-grade twins. We’ve been working together for an hour in a small auditorium in a walled compound outside Kigali. A choir practices somewhere outside, the ethereal music blending with the clouds that descend down the green ravines of thehills that define Rwanda. Although hespeaks no English and I no Kinyarwanda,we use the universal signs of thumbs-ups,head nods, and “no problem.” We work asa team.And we smile. A lot. The kid has a smilelike no other I’ve seen in more than sixyears of working with African relief agencies to build and donate bikes to charitable groups. I’ve seen lots of hard workers. Lots of incredible people. But there’s something about this one that has a hold, quite unexpectedly, of my heart, more so than the other kids working with volunteers around the compound.Maybe because he’s about the same age as my own three children, a world away in an American suburb. Maybe it’s his warmth, laid bare by a complete absence of any artifice. His eyes glow and his teeth sparkle, and my jet lag melts away as this kid, whose name I don’t know and can’t seem to find out, beams with pride and happiness at finally getting the pedals onto the bike. I give him a thumbs-up, and he beams anew. Over the course of this humid morning, we’ll assemble 15 or so bikes, half of what I could do working alone. But I have a new friend.And he likes me. Anytime we stop work so I can explain something to him, he holds my hand. When we stop for tea, he holds my hand again, and I slip him some Skittles. A woman in traditional dress comes over, ignoring me, and speaks to him sharply, then raps his hand. I’m shocked, but parenting methods are different in central Africa than in New Jersey, so I say nothing as he struggles to hold back tears. Then he takes my hand and pulls me back to the bikes. Within two minutes, he’s beaming, and this time, I’m the one trying to hold back tears.At lunch, I tell Jules Shell, the director of Foundation Rwanda, the charity group we’re working with, what a great hustler we have on our hands. I ask again what his name is. She says, “Well, we call him Jean-Paul. But he doesn’t have a real name.”I must look confused. She smiles a little. “I don’t think his mom could bring herself to call him anything at the time.”I don’t get it, but she continues. “How old do you think he is?” she asks.“Nine, maybe ten,” I say.She looks at me with the tired eyes of a relief worker exhausted by explaining the unexplainable. “He’s 16,” she says. I say it can’t be; he’s tiny. “Sixteen. All these kids are. The genocide was in 1994. Do the math.”At the Vietnam Veterans MemorialOn March 26, 1982, Emogene Cupp stood on a grassy site in Washington, D.C. to take part in a historic event: the breaking of ground for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the luminescent black wall now inscribed with the names of more than 58,000 Americans who were killed inVietnam or remain missing. One of those names belongs to Cupp’s son, Robert. Today, March 26, 2012, she was back to attend an official ceremonycelebrating the memorial’s 30th anniversary. Carrying theshovel she received at the groundbreaking three decadesago, Cupp, now 92, was there to honor her son, who waskilled in June 1968 and buried on his 21st birthday. “I misshim,” she said.On this glorious spring day, Cupp, along with other familymembers, Vietnam veterans, elected officials and decorated war heroes joined Jan C. Scruggs, founder and president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), for the commemoration. Speakers, including Brigadier General George B. Price and General Barry McCaffrey, saluted the nation’s servicemen and women, past and present. They lauded the memorial as a place for healing, and applauded the VVMF’s future education center, which will include photos and stories of those who served. Scruggs, who conceived the idea of a memorial and helped raise more than $8 million to bu ild it, told Reader’s Digest, “It’s a great example of three million people who were willing to do what their country asked them to do.” He continued, “These are people who loved their country—and that’s their legacy.”Steve Nelson feels that legacy very personally. Nelson was 19 when he went to serve in Vietnam and Cambodia between April 1969 and October 1970. Eleven men from his unit and his best friend were killed. Among other injuries, Nelson took a bullet in his back and his shoulder. Twenty-five years ago, Nelson spent two nights sleeping in shrubs near the memorial, where he contemplated ending his life. A fellow vet helped save him. Today, he was back to commemorate the wall and the people on it. “I live for these guys, because they didn’t live,” sai d Nelson, now 62, as he pointed to the memorial. “This here makes me feel good.”The Birth of a FamilyDavid Marin was in his early 40s, longing to be a dad.“I’d led an interesting life,” he writes in his new book, “traveled to 11 countries, jumped out of airplanes, graduated from law school, and I’d had three holes in one.” But as a divorced single man, his dream of raising kids eluded him.“At night, I imagined the worst: sittingalone and retired … watching familiesdrive by.” Marin decided to adopt f romfoster care. Although more than 500,000kids are in the foster system in the UnitedStates — one quarter of them available foradoption — the process of winningapproval proved arduous. Marin, who wasvice president of advertising at Pulitzer Newspapers in Santa Maria, California, endured miles of bureaucratic red tape, vetting by two counties, three rounds of fingerprinting, and frustrating delays (a required home-safety class, for instance, was postponed twice). In September 2003, 14 months after he’d first made inquiries about adoption, Social Services called him about three siblings (from the same mother, different fathers —all felons). In December, Marin met the kids. Then came a month of “Family Practice” — weekend and evening visits, with follow-up calls to a social worker.Finally, on February 27, 2004, Marin brought home Craig, two; Adriana, four; and Javier, six, for good. The new family was often met with stares and suspicion (one woman at a restaurant where they were eating called the police, worried that Marin was doing something inappropriate). But the hurdles of this adoption were nothing compared with its joys, says Marin. In this excerpt, he writes about the challenges with his youngest child, Craig, and how, together, he and the kids overcame them.Craig’s life was a cartoon. He was the prey, like Jerry the mouse running away from Tom the cat, or the Road Runner chased by Wile E. Coyote. But two-year-old Craig was neither clever like Jerry nor fast like the Road Runner, so in real life, he probably only whimpered when the predators, his mother and her boyfriends, laid into him. When I first held Craig to smell his baby hair — my dumbbells weighed more than he did — he just held on, waiting for the drop or the throw.Craig didn’t speak; he pointed and grunted. When I told people he didn’t talk, they would ask me his age. After I said he was almost two and a half, they’d turn away. That’s not good, the turning away.He put his clothes on backward and had a hard time keeping up on walks to the Santa Maria river levee, so he rode in the stroller. If we walked for long and his little legs grew tired, I’d hoist him onto my shoulders. He liked heights and a breeze in his face, and when I pushed him in the swing, he wanted to go higher than the clouds, away from it all. He fearlessly climbed the jungle gym, but if a dog came near, he ran toward me until he saw it was a squirrel the dog chased, not him. Nothing was smaller than Craig. He was always looking around; there was danger ahead and behind and, with hawks, above. He could not communicate the truths of his early life, and I had no records or files for him —Social Services didn’t even know his name was Craig; they’d been calling him Chris. He just came along with Javier and Adriana.I worried because he was so frail. During Family Practice, a social worker called me.“Hi, David. Has anyone told you that you have to wake Chris up every night?”“No. His name is Craig.”“Craig? Well, anyway, you have to wake him up every two hours to see if his nose is bleeding. He has bad nosebleeds.”I was game but ill-prepared. One morning I found Craig lying in a pool of blood in his bed. I rushed him to a doctor, who said Craig’s fingernails could be shorter and maybe he was picking his nose. I felt ashamed: It was my job to notice that.To Serve and ProtectHernandez says the real heroes are the doctors, paramedics, and public servants.Daniel Hernandez always knew he wanted to help people. Before he’d even graduated high school, he trained to be a certified nursing assistant and volunteered at a nursing home. A big kid with a gentle, efficient manner, he learned to use needles to draw blood, to lift patients in his strong arms, and to respond swiftly andcalmly to emergencies.He never quite got around to taking theexam to become fully certified, though,because by then he’d decided he wanted towork in public service. He felt inspired bythe good that responsible lawmakers cando, so in his junior year at the Universityof Arizona, he declared a major in politicalscience and began volunteering in political campaigns. One of his heroes was his local congresswoman, Gabrielle Giffords. He’d met Giffords while he was working on Hillary Clinton’spresidential campaign and thought Giffords was not just a trailbla zer but “the kindest, warmest human being you will ever meet in your entire life.”He was elated when he was picked for an internship with her, and he gladly gave up a part-time sales job for the chance to work on her team. So eager was he that he started work four days early. On Saturday morning, January 8, he arrived at La Toscana Village mall north of Tucson and began setting up tables in front of a Safeway store where 30 or so people were gathering to meet Giffords. It was Hernandez’s job to sign people in and guide them into a queue so each could get a photo taken with the congresswoman between an American and an Arizona State flag.At 10:10 a.m., Hernandez heard loud popping sounds. “Gun!” someone yelled. He heard people screaming, saw them falling to the ground. Hernandez was standing 30 feet away from Giffords when she collapsed. In seconds, he was at her side. “When I heard gunfire, I figured there was danger to the congresswoman,” he recalls. “I started toward her.”Everywhere around him was chaos, but Hernandez willed himself to remain calm. “I tried to tune everything out and keep an intense focus. I didn’t want to let my emotions become part of the problem.”Giffords was lying on the sidewalk; blood was streaming down her face from a bullet wound to her head. Gently, Hernandez lifted her into a sitting position against his shoulder so she wouldn’t choke on her blood. Then, with his bare hand, he applied pressure to the wound on her forehead to staunch the flow of blood. She was conscious; he calmed her and told her all would be well. Minutes later, ambulances and paramedics arrived on the scene. Still Hernandez stayed with Giffords, holding her hand and talking. “I just made sure she knew she wasn’t alone,” he says. “When I told her I’d contact [her husband] Mark, she squeezed my hand hard.”Nineteen people fell victim to a deranged man with a deadly weapon that day. Six died. Giffords, though gravely wounded, survived —in no small part because of Hernandez’s quick and selfless actions. Says surgeon Peter Rhee, chief of trauma at University Medical Center in Tucson, where Giffords was taken, Hernandez “was quick to act —he did a heroic thing.”Hernandez never talks about those horrible minutes in a Tucson parking lot without mentioning the people he sees as the real miracle workers: the paramedics and doctors and the public servants who spend their lives helping others —and sometimes give their lives that way. He doesn’t see himself as a hero. The people of Tucson and the nation beg to differ. They’re grateful Daniel Hernandez felt driven to be of service — felt called so strongly, in fact, that he was there at that fateful moment, four days earlier than he was supposed to be. He puts it simply. “Sometimes,” he says, “I wonder if there was a reason for me to be there.”The Memorial Garden MiracleHurricane Irene might have been gentler than expected in some quarters, but in West Hartford, Vermont, it produced a surreal and frightening landscape. The White River jumped its banks and sent waves of contaminated water into nearby homes. Shipping containers, propane tanks, and even entire trucks were spotted washing down the river near Patriots’ Bridge in the middle of the night.Patti and Scott Holmes had a specialconnection to the flood zone. Their son,Marine Lance Cpl. Jeffery Holmes, wasone of three fallen warriors honored on amonument in a memorial garden next to thebridge. Jeffery died on Thanksgiving Day2004 in Fallujah during Operation IraqiFreedom. He was shot in the neck duringan ambush and a rocket-propelled grenade destroyed his legs. Patti took some comfort knowing that her son had perished instantly, serving the military he wanted to join since he was nine years old.The August hurricane spared Patti and Scott’s home. Patti didn’t realize how bad the situation had been at the monument site until one of Jeff’s friends sent a photo the next day. “When I opened it, I just started crying,” she says. All the flowers that volunteers lovingly tended were gone. The granite monument had toppled off its concrete base and was likely ruined. Alone at her desk, Patti wept for the fun-loving blue-eyed son who didn’t live to see his 21st birthday, the boy she still wrote on Christmas and birthdays. Now another piece of him had slipped away.Scott drove to the bridge that night to see exactly what had happened but was forced to turn back. The torrential flooding had destroyed roads, dented railings on the bridge, and propelled a modular home into the middle of a street. Who knows how the angry waters had ravaged the monument? But when Patti and Scott were finally able to get there later in the week, they were greeted with an extraordinary sight. Local residents had returned the monument to its proper place, unharmed. “I didn’t see a scratch, not even on top of it,” Patti marveled in joy and relief.Friends have vowed to help Patti and Scott replant the garden. Come spring, irises, daisies and other flowers in hues of red, white, and blue will surround this community treasure, which is once again standing tall.Merry, Silly ChristmasMy best Christmas was the year we had Ken and Barbie at the top of our tree. We had an angel first, for Christmas Day, but then we had Ken and Barbie. Let me explain. When my daughter was four, I hired a ballet dancer to babysit for a few afternoons a week. Randy was tall and confident, with that dancer’s chest-first carriage, and, though he was only 27, a sure, cheerful bossiness. For four years, he and Halley roamed the city on adventures: to climb the Alice in Wonderland statuein Central Park, to smile at the waddling,pint-sized penguins at the zoo. They hadtheir own world, their own passions: adevotion to ice cream, to Elmo, to Pee-weeHerman.He orchestrated Halley’s birthday partiesto a fare-thee-well: One year he declared aPeter Pan theme, made Halley a TinkerBell outfit with little jingle bells at the hem, and talked my father into making a scary appearance in a big-brimmed pirate hat and a fake hook for a hand. Randy took charge of my grown-up parties, too, dictating what I wore, foraging in thrift shops to find the right rhinestone necklace to go with the dress he’d made me buy.When Halley was eight, Randy left New York to take over a sleepy ballet company in a small city in Colorado. He taught, he choreographed, he coaxed secretaries and computer salesmen intopliéing across the stage.Halley missed him terribly, we all did, but he called her and sent her party dresses, and he came to see us at Christmas when he could. The year Halley was ten, we had a new baby. That same year, Randy was diagnosed with AIDS. He told me over the phone, without an ounce of self-pity, that he had so few T cells left that he’d named them Huey, Dewey, and Louie.It seemed insane for him to travel, insane for him to risk one of us sneezing on him and giving him pneumonia, but he had decided, and that was it. He was as cheerful and bossy as ever. Terribly thin, his cheeks hollow but eyes bright, he took Halley all over the city once again, with baby Julie strapped to his chest in a cloth carrier.“We’ve got to do something about this tree,” he said one day. The tree, with its red ribbon bows, looked fine to me; I was even a little vain about the way every branch shone with ornaments.A few days later, on New Year’s Eve morning, he sum moned our little family. He was wearing the old pirate’s hat, fished out of a costume box and, for hair, curly colored streamers that stuck out of the hat and tumbled down to his shoulders.As we watched — me irritable at first, wondering how much you were supposed to yield to a dying houseguest, even if you loved him like a brother — he stripped the tree. Then he brought out more curly streamers, heaps of them, and tooters and little party-favor plastic champagne bottles. “Now we’ll turn it into a New Year’s tree,” he declared.A New Year’s tree! Of course! We threw the streamers all over the tree, we covered it with the tooters and the tiny champagne bottles. “And now, for the pièce de résistance,” Randy said. Stretching his tall self way up to the top of the tree, he removed its gold papier-mâché angel. Solemnly, carefully, he placed on top Halley’s tuxedoed Ken and her best Barbie, the one in a sparkly ball gown.“Ta da!” he said, and beamed. It was a wonderful tree, happy and goofy and perfect.Randy lived for another year and a half. None of us will ever get over his death, not really. But every Christmastime, I raise a glass to Randy — to his tree, to his bossiness, to the Christmas he taught us that courage is a man in a pirate hat with silly streamers for hair.Sharing the SweetnessOn the 25th of December, my mother expects her children to be present and accounted for, exchanging gifts and eating turkey. When she pulls on that holiday sweater, everybody better get festive. Of course, I would be the first Jones sibling to go rogue. As the middle, artist child, I was going to strike out and do my own thing, make some new traditions. From a biography of Flannery O’Connor, I drew inspiration —I would spend the holiday at an artistcolony!No one took the news very well. From theway my mother carried on, you wouldthink that I was divorcing the family. Still,I held my ground and made plans for mywinter adventure in New Hampshire. TheMacDowell Colony was everything Icould have wished for. About 25 to 30 artists were in attendance, and it was as, well, artsy as I had imagined. It felt like my life had become a quirky independent film.By Christmas Eve, I had been at the colony more than a week. The novelty of snowy New England was wearing off, but I would never admit it. Everyone around me was having too much fun. Sledding and bourbon! Deep conversations by the fireplace! And that guy with the piercings. So cute! What was wrong with me? This was the holiday I’d always dreamed of. No plasticreindeer grazing on the front lawn. No football games on TV. Not a Christmas sweater anywhere in sight. People here didn’t even say “Christmas,” they said “holiday.” Utter sophistication. Then why was I so sad?Finally, I called home on the pay phone in the common room. My dad answered, but I could barely hear him for all the good-time noise in the background. He turned down the volume on the Stevie Wonder holiday album and told me that my mother was out shopping with my brothers. Now it was my turn to sulk. They were having a fine Christmas without me.Despite a massive blizzard, a large package showed up near my door at the artist colony on Christmas morning. Tayari Jones was written in my mother’s beautiful handwriting. I pounced on that parcel like I was five years old. Inside was a gorgeous red-velvet cake, my favorite, swaddled in about 50 yards of bubble wrap. Merry Christmas, read the simple card inside. We love you very much.As I sliced the cake, everyone gathered around — the young and the old, the cynical and the earnest. Mother had sent a genuine homemade gift, not trendy or ironic. It was a minor Christmas miracle that one cake managed to feed so many. We ate it from paper towels with our bare hands, satisfying a hunger we didn’t know we had.Some Assembly RequiredMy five-year-old daughter knew exactly what she wanted for Christmas of 1977, and told me so. Yes, she still would like the pink-and-green plastic umbrella with a clear top she’d been talking about. Great to observe patterns of rain spatters. Books, long flannel nightgown, fuzzy slippers —fine. But really, there was only one thing that mattered: a Barbie Townhouse, with all the accessories.This was a surprise. Rebecca was not aBarbie girl, preferred stuffed animals todolls, and wasn’t drawn to play in astructured environment. Always a make-up-the-rules, design-your-own-world,do-it-my-way kid. Maybe, I thought, thepoint wasn’t Barbie but house, adomicile she could claim for herself,since we’d already moved five times during her brief life.Next day, I stopped at the mall. The huge Barbie Townhouse box was festooned with exclamations: “3 Floors of High-Styled Fun! Elevator Ca n Stop on All Floors!” Some Assembly Required.Uh-oh. My track record for assembling things was miserable. Brooklyn-born, I was raised in apartment buildings in a family that didn’t build things. A few years earlier, I’d spent one week assembling a six-foot-tall jungle gym from a kit containing so many parts, I spent the first four hours sorting and weeping and the last two hours trying to figure out why there were so many leftover pieces. The day after I finished building it, as if to remind me of my limitations, a tornado touched down close enough to scatter the jungle gym across an acre of field.I assembled the Barbie Townhouse on Christmas Eve. Making it level, keeping the columns from looking like they’d melted and been refrozen, and getting that eleva tor to work were almost more than I could manage. And building it in curse-free silence so my daughter would continue sleeping — if, in fact, she was sleeping — added a layer of challenge. By dawn I was done.Shortly thereafter, my daughter walked into the living room, stuffed bear tucked under her arm, feigning shock and looking as tired as I did. Her surprise may have been sham, but her delight was utterly genuine and moves me to this day, 34 years later. Rebecca had spurred me to do something I didn’t th ink I could do. It was for her, and — like so much of the privilege of being her father —it brought me further outside myself and let me overcome doubts about my capacities.Now that I think about it, there probably was real surprise in her first glimpse of her Barbie Townhouse. Not, perhaps, at the gift itself but that it had been built and remained standing in the morning light. Or maybe it was simpler than that: Maybe she was surprised because she’d planned on building the thing herself.All I’m Asking ForI must have been about nine years old, too dignified to sit on Santa’s lap at the Mason’s department store in Anniston, Alabama, but still young enough to ask — please, please, please —for a G.I. Joe. “You’re too old to play withdolls,” my brother Sam hissed at me. Samnever was a child. My kin liked to say theday he was born, he dusted himself off inthe delivery room and walked home.“G.I. Joe ain’t no doll,” I hissed back, myface red.“Is,” Sam said.。

英美报刊文章选读feature story2

If you ask the question "how and why" things happen, then you probably like reading feature stories in newspapers and magazines. What is a feature story? A feature takes an in-depth look at what’s going on behind the news.

It gets into the lives of people. It tries to explain why and how a trend developed. Unlike news, a feature does not have to be tied to a current event or a breaking story. But it can grow out of something that’s reported in the news.

UNICEF estimates that about 1.2 million women and children are trafficked annually. The majority of them are trafficked out of Asia and Eastern Europe, especially the republics of the former Soviet Union. UN officials say that governments who signed onto the global antichild trafficking drive in Japan in 2001 must urgently tackle the root causes of the human slave trade, such as povery and inequality.

英语报刊选读读者文摘原文版INSPIRINGSTORIES(3)

英语报刊选读读者⽂摘原⽂版INSPIRINGSTORIES(3)Father TimeI lost my dad last year.Sure, lots of memorable stuff happened to me in 2011. My daughters started first grade. I read and will never forget Unbroken.I did a pull-up for the first time!But Dad’s passing? That defines last year for me. It signals a shiftin all the many things uniquely us: Michigan football. ClevelandStadium mustard. Knowing how to parallel park, change a tire, andbalance a checkbook the “right way.” Handwritten letters on hisLudlow Antiques stationery to his homesick firstborn at U of M. An appreciation for Neil Diamond (shhh). And, did I mention, Michigan football?“Good job on the Today show, honey,” he’d say. “Very informative. Was that a new blouse?” I came to realize the expanse of the void when, late last fall, I got this job — the job of being the editor-in-chief of your Reader’s Digest, the most trusted magazine in America. I was humbled by the opportunity. Incredulous, really. I texted friends, war-dialed my sister. But first I told Mom, who said the one thing I needed to hear: “I wish your father were here. He would be so proud, honey.”That’s my intent, as I shepherd Reader’s Digest and its website, books, and apps through the coming years. I hope to do him — and you — proud. Oh , and I’ll try to keep the Michigan football stuff to a minimum. Though Tom Brady? Michigan. I’m just sayin g ’.The Titanic Coat: One Family’s LegendIn an inspiring follow-up to the Titanic story, Reader's Digest national affairs editor David Noonan tells of a family heirloom that survived the fatal tragedy on April 15, 1912.My great uncle Denis O’Brien boarded the Titanic as a third -class passenger at Queenstown, Ireland. He was 21, a jockey from County Cork who wasoffered a job riding horses for an American family. Hisolder brother Michael, my grandfather, who had made hisown trip across the Atlantic a few years earlier, waswaiting for him in New York. In one version of thestory —different family members recall hearing differentINSPIRING STORIES 3details over the years—Michael sent Denis a proper overcoat so he wouldn’t look too poor when he came through Ellis Island. That may or may not be true. What we know for sure is that Denis didn’t make it, though his overcoat did.As the ship was sinking, Denis, who is sometim es listed as Timothy O’Brien in Titanic passenger records, wrote a note to Michael. He gave the note and his overcoat to a woman in a lifeboat and asked her to see that his brother got them. She did.A photo of my grandfather wearing what we have always ca lled “the Titanic coat” holds a special place in the family archives. In the picture, he looks small and dapper and not poor at all.No one knows what the note said—that part of the story got lost over the course of the past hundred years—and I often wonder what few words Denis chose that night. I also wonder what he was thinking later, as he stood on that tilting deck with no coat and faced the end of his too-short life in that cold ocean, beneath those cold stars.The Night I Met EinsteinWhen I was a very young man, just beginning to make my way, I was invited to dine at the home of a distinguished New York philanthropist. After dinner, our hostess led us to an enormous drawing room. Other guests were pouring in, and my eyes beheld two unnerving sights: Servants were arranging small gilt chairs in long, neat rows; and up front, leaning against the wall, weremusical instruments.Apparently I was in for an evening of chamber music.I use the phrase “in for” because music meant nothing to me.I am almost tone deaf—only with great effort can I carry thesimplest tune, and serious music was to me no more than anarrangement of noises. So I did what I always did whentrapped: I sat down, and when the music started, I fixed my face in what I hoped was an expression of intelligent appreciation, closed my ears from the inside, and submerged myself in my own completely irrelevant thoughts.After a while, becoming aware that the people around me were applauding, I concluded it was safe to unplug my ears. At once I heard a gentle but surprisingly penetrating voice on my right: “You are fond of Bach?”I knew as much about Bach as I know about nuclear fission. But I did know one of the most famous faces in the world, with the renowned shock of untidy white hair and the ever-present pipe between the teeth. I was sitting next to Albert Einstein.“Well,” I said uncomfortably and hesitated. I had been asked a casual question. All I had to do was be equally casual in my reply. But I could see from the look in my neighbor’s e xtraordinary eyes that their owner was not merely going through theperfunctory duties of elementary politeness. Regardless of what value I placed on my part in the verbal exchange, to this man his part in it mattered very much. Above all, I could feel that this was a man to whom you did not tell a lie, however small.“I don’t know anything about Bach,” I said awkwardly. “I’ve never heard any of his music.”A look of perplexed astonishment washed across Einstein’s mobile face.“You have never heard Bach?”H e made it sound as though I had said I’d never taken a bath.“It isn’t that I don’t want to like Bach,” I replied hastily. “It’s just that I’m tone deaf, or almost tone deaf, and I’ve never really heard anybody’s music.”A look of concern came into the old man’s face. “Please,” he said abruptly. “You will come with me?”He stood up and took my arm. I stood up. As he led me across that crowded room, I kept my embarrassed glance fixed on the carpet. A rising murmur of puzzled speculation followed us out into the hall. Einstein paid no attention to it.Resolutely, he led me upstairs. He obviously knew the house well. On the floor above, he opened the door into a book-lined study, drew me in, and shut the door.“Now,” he said with a small, troubled smile. “You will tell me, please, how long you have felt this way about music?”“All my life,” I said, feeling awful. “I wish you would go back downstairs and listen, Dr. Einstein. The fact that I don’t enjoy it doesn’t matter.”Einstein shook his head and scowled, as though I had introduced an irrelevance.“Tell me, please,” he said. “Is there any kind of music that you do like?”“Well,” I answered, “I like songs that have words, and the kind of music where I can follow the tune.”He smiled and nodded, obviously pleas ed. “You can give me an example, perhaps?”“Well,” I ventured, “almost anything by Bing Crosby.”He nodded again, briskly. “Good!”He went to a corner of the room, opened a phonograph, and started pulling out records. I watched him uneasily. At last, he be amed. “Ah!” he said.。

美英报刊阅读教程Lesson 1 课文

【Lesson 1 Good News about Racial ProgressThe remaining divisions in American society shouldnot blind us to a half-century of dramatic changeBy Abigail and Stephan ThernstromIn the Perrywood community of Upper Marlboro, Md.1, near Washington, D.C., homes cost between $160,000 and $400,000. The lawns are green and the amenities appealing—including a basketball court.Low-income teen-agers from Washington started coming there. The teens were black, and they were not welcomed. The homeowners’ association hired off-duty police as security, and they would ask the ballplayers whether they “belonged” in the area. The association’ s newsletter noted the “eyesore” at the basketball court.But the story has a surprising twist: many of the homeowners were black t oo. “We started having problems with the young men, and unfortunately they are our people,” one resident told a re porter from the Washington Post. “But what can you do?”The homeowners didn’t care about the race of the basketball players. They were outsiders—in truders. As another resident remarked, “People who don’t live here might not care about things the way we do. Seeing all the new houses going up, someone might be tempted.”It’s a t elling story. Lots of Americans think that almost all blacks live in inner cities. Not true. Today many blacks own homes in suburban neighborhoods—not just around Washington, but outside Atlanta, Denver and other cities as well.That’s not the only common misconception Americans have ab out race. For some of the misinformation, the media are to blame. A reporter in The Wall Street Journal, for instance, writes that the economic gap between whites and blacks has widened. He offers no evidence. The picture drawn of racial relations is even bleaker. In one poll, for instance, 85 percent of blacks, but only 34 percent of whites, agreed with the verdict in the O.J. Simpson murder trial. That racially divided response made headline news. Blacks and whites, media accounts would have us believe, are still separate and hostile. Division is a constant theme, racism another.To be sure, racism has not disappeared, and race relations could —and probably will —improve. But the serious inequality that remains is less a function of racism than of the racial gap in levels of educational attainment, single parenthood and crime. The bad news has been exaggerated, and the good news neglected. Consider these three trends:A black middle class has arrived. Andrew Young recalls the day he was mistaken for a valet at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. It was an infuriating case of mistaken identity for a man who was then U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.But it wasn’t so long ago that most blacks were servants—or their equivalent. On the eve ofWorld War II, a trivial five percent of black men were engaged in white-collar work of any kind, and six out of ten African-American women were employed as domestics.In 1940 there were only 1,000 practicing African-American lawyers; by 1995 there were over 32,000, about four percent of all attorneys.Today almost three-quarters of African-American families have incomes above the government poverty line. Many are in the middle class, according to one useful index—earning double the government poverty level; in 1995 this was $30,910 for a two-parent family with two children and $40,728 for a two-parent family with four children. Only one black family in 100 enjoyed a middle-class income in 1940; by 1995 it was 49 in 100. And more than 40 percent of black households also own their homes. That’ s a huge change.The typical white family still earns a lot more than the black family because it is more likely to collect two paychecks. But if we look only at married couples—much of the middle class—the white-black income gap shrinks to 13 percent. Much of that gap can be explained by the smaller percentage of blacks with college degrees, which boost wages, and the greater concentration of blacks in the South, where wages tend to be lower.Blacks are moving to the suburbs. Following the urban riots of the mid-1960s, the presidential Kerner Commission14 concluded that the nation’ s future was menaced by “accelerating segregation”—black central cities and whites outside the core. That segregation might well blow the country apart, it said.It’ s true that whites have continued to leave inner cities for the suburbs, but so, too, have blacks. The number of black suburban dwellers in the last generation has almost tripled to 10.6 million. In 1970 metropolitan Atlanta, for example, 27 percent of blacks lived in the suburbs with 85 percent of whites. By 1990, 64 percent of blacks and 94 percent of whites resided there.This is not phony integration, with blacks moving from one all-black neighborhood into another. Most of the movement has brought African-Americans into neighborhoods much less black15 than those they left behind, thus increasing integration. By 1994 six in ten whites reported that they lived in neighborhoods with blacks.Residential patterns do remain closely connected to race. However, neighborhoods have become more racially mixed, and residential segregation has been decreasing.Bigotry has declined. Before World Was ft, Gunnar Myrdal16 roamed the South researching An American Dilemma, the now-classic book that documented17 the chasm betwe en the nation’s ideals and its racial practices, hi one small Southern city, he kept asking whites how he could find “Mr. Jim Smith,” an African-American who was principal of a black high school. No one seemed to know who he was. After he finally found Smith, Myrdal was told that he should have just asked for “Jim.” That’ s how great was white aversion to dignifying African-Americans with “Mr.” Or “Mrs.”Bigotry was not just a Southern problem. A national survey in the 1940s asked whether “Ne-groes shoul d have as good a chance as white people to get any kind of job.” A majority of whites said that “white people should have the first chance at any kind of job.”19. Such a question would not even be asked today. Except for a lunatic fringe18, no whites would sign on to such a notion.1920. In 1964 less than one in five whites reported having a black friend. By 1989 more than two out of three did. And more than eight often African -Americans had a white friend.21. What about the last taboo?20 In 1963 ten percent of whites approved of black-white dating; by 1994 it was 65 percent. Interracial marriages? Four percent of whites said it was okay in 1958; by 1994 the figure had climbed more than elevenfold, to 45 percent. These surveys measure opinion, but behavior has also changed. In 1963 less than one percent of marriages by African- Americans were racially mixed. By 1993, 12 percent were.22. Today black Americans can climb the ladder to the top.21 Ann M. Fudge is already there; she’s in charge of manufacturing, promotion and sales at the $2.7-billion Maxwell House Coffee and Post Cereals divisions of Kraft Foods.22 So are Kenneth Chenault, president and chief operating officer at American Express23 and Richard D. Parsons, president of Time Warner, Inc.24 After the 1988 Demo-cratic Convention25, the Rev. Jesse Jackson26 talked about his chances of making it to the White House. “I may not get there,” he said “But it is possible for our children to get there now.”23. Even that seems too pessimistic. Consider how things have improved since Colin and Alma Powell27 packed their belongings into a V olkswagen28 and left Fort Devens, Mass., for Fort Bragg, N. C. “I remember passing Woodbridgc, Va.,” General Powell wrote in his autobiogra phy, “and not finding even a gas-station bathroom that we were allowed to use.” That was in 1962. In 1996 reliable polls suggest he could have been elected President.24. Progress over the last half-century has been dramatic. As Corctta Scott King wrote not long ago, the ideals for which her husband Martin Luther King Jr. died, have become “deeply embedded in the very fabric of America29.”From Reader’s Digest, March, 1998V. Analysis of Content1. According to the author, ___________A. racism has disappeared in AmericaB. little progress has been made in race relationsC. media reports have exaggerated the racial gapD. media accounts have made people believe that the gap between blacks and whites has become narrower2. What the Kerner Commi ssion meant by “accelerating segregation” was that __________A. more and more whites and blacks were forced to live and work separatelyB. more and more blacks lived in the central cities, and whites outside the coreC. more and more whites lived in the central cities, and blacks outside the coreD. nowadays more and more blacks begin to live in the suburbs3. The last taboo in the article is about ____________.A. political status of America’s minority peopleB. economic status of America’ s minori ty peopleC. racial integrationD. interracial marriages4. Gunnar Myrdal kept asking whites how he could find “Mr. Jim Smith,” but no one seemed to know who he was, because _____________.A. there was not such a person called Jim SmithB. Jim Smith was not famousC. the whites didn ‘t know Jim SmithD. the white people considered that a black man did not deserve the title of “Mr.”5. In the author’s opinion, _A. few black Americans can climb the ladder to the topB. Jesse Jackson’ s words in th is article seemed too pessimisticC. Colin Powell could never have been elected PresidentD. blacks can never become America’ s PresidentVI. Questions on the Article1. Why were those low-income teen-agers who came to the Perrywood community consid-ered to be “the eyesore”?2. What is the surprising twist of the story?3. According to this article, what has caused much of the white-black income gap?4. Why did the presidential Kerner Commission conclude that the nation’ s future was menaced by “accelerating segregation”?5. Why wouldn’t questions as “Should negroes have as good a chance as white people to get any kind of job?” be asked today?Topics for Discussion1. Can you tell briefly the dramatic progress in the status of America’ s minority p eople over the last half-century?2. Do you think the article is unbiased? What do you think of the author s view on the African-Americans?1. amenity: n. A. The quality of being pleasant or attractive; agreeableness. 怡人:使人愉快或吸引人的性质;使人愉快 B. A feature that increases attractiveness or value, especially of a piece of real estate or a geographic location.生活福利设施;便利设施:能够增加吸引力或价值的事物,特别是不动产或地理位置⊙ We enjoy all the -ties of home life. 我们享受家庭生活的一切乐趣。

最新英美报刊选读—Unit 1

最新英美报刊选读_Unit 1 serving Languages Is About More Than Words

Language Features Background Information WarmingWarming-up Questions Organization Analysis Detailed Reading PostPost-Reading

最新英美报刊选读_Unit 1 Focus

WarmingWarming-up Questions

What can we do to preserve dying language?

• Already, after only a few weeks of work, the students are well on their way to reaching their first-year goal to create a dictionary with 1,500 entries and a lesson plan to be used throughout the year. • They have also begun teaching classes to many of the community’s children and adults. Beier said that an average of 20 adults and 35 youth, ranging in age from 6 to 16, attend their classes—a significant portion of San Antonio’s total population of about 400 people.

最新英美报刊选读_Unit 1 Focus

英美报刊选读_课文word整合版