Q.A & Q.C必备常识--验货流程

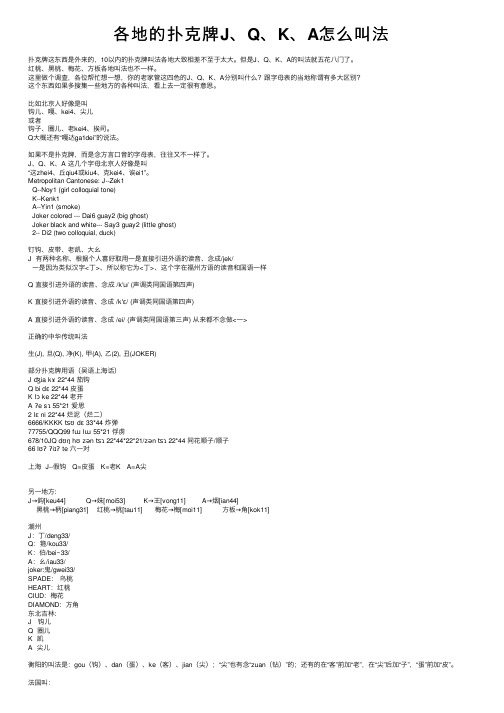

各地的扑克牌J、Q、K、A怎么叫法

各地的扑克牌J、Q、K、A怎么叫法扑克牌这东西是外来的,10以内的扑克牌叫法各地⼤致相差不⾄于太⼤。

但是J、Q、K、A的叫法就五花⼋门了。

红桃、⿊桃、梅花、⽅板各地叫法也不⼀样。

这⾥做个调查,各位帮忙想⼀想,你的⽼家管这四⾊的J、Q、K、A分别叫什么?跟字母表的当地称谓有多⼤区别?这个东西如果多搜集⼀些地⽅的各种叫法,看上去⼀定很有意思。

⽐如北京⼈好像是叫钩⼉、嘎、kei4、尖⼉或者钩⼦、圈⼉、⽼kei4、挨司。

Q⼤概还有“嘎达ga1dei”的说法。

如果不是扑克牌,⽽是念⽅⾔⼝⾳的字母表,往往⼜不⼀样了。

J、Q、K、A 这⼏个字母北京⼈好像是叫“这zhei4、丘qiu4或kiu4、克kei4、诶ei1”。

Metropolitan Cantonese: J--Zek1Q--Noy1 (girl colloquial tone)K--Kenk1A--Yin1 (smoke)Joker colored --- Dai6 guay2 (big ghost)Joker black and white--- Say3 guay2 (little ghost)2-- Di2 (two colloquial, duck)钉钩、⽪带、⽼凯、⼤⼳J 有两种名称、根据个⼈喜好取⽤⼀是直接引进外语的读⾳、念成/jek/⼀是因为类似汉字<丁>、所以称它为<丁>、这个字在福州⽅语的读⾳和国语⼀样Q 直接引进外语的读⾳、念成 /k'u/ (声调类同国语第四声)K 直接引进外语的读⾳、念成 /k'ε/ (声调类同国语第四声)A 直接引进外语的读⾳、念成 /ei/ (声调类同国语第三声) 从来都不念做<⼀>正确的中华传统叫法⽣(J), 旦(Q), 净(K), 甲(A), ⼄(2), 丑(JOKER)部分扑克牌⽤语(吴语上海话)J ʤia kɤ 22*44 茄钩Q bi dɛ 22*44 ⽪蛋K lɔ ke 22*44 ⽼开A ʔe sɿ 55*21 爱思2 lɛ ni 22*44 烂泥(烂⼆)6666/KKKK ʦʊ dɛ 33*44 炸弹77755/QQQ99 fɯ lɯ 55*21 俘虏678/10JQ dʊŋ hʊ zən ʦɿ 22*44*22*21/zən ʦɿ 22*44 同花顺⼦/顺⼦66 lʊʔʔiɪʔ te 六⼀对上海 J--假钩 Q=⽪蛋 K=⽼K A=A尖另⼀地⽅:J→鈎[keu44] Q→妹[moi53] K→王[vong11] A→烟[ian44]⿊桃→柄[piang31] 红桃→桃[tau11] 梅花→梅[moi11] ⽅板→⾓[kok11]潮州J:丁/deng33/Q:箍/kou33/K:伯/bei~33/A:⼳/iau33/joker:⿁/gwei33/SPADE:乌桃HEART:红桃CIUD:梅花DIAMOND:⽅⾓东北吉林:J 钩⼉Q 圈⼉K 凯A 尖⼉衡阳的叫法是:gou(钩)、dan(蛋)、ke(客)、jian(尖);“尖”也有念“zuan(钻)”的;还有的在“客”前加“⽼”,在“尖”后加“⼦”,“蛋”前加“⽪”。

aq开头的标准

AQ 开头的标准是指国家安全生产监督管理总局发布的一系列安全生产行业标准。

这些标准是为了提高安全生产水平,预防和减少事故发生,保障人民群众生命财产安全而制定的。

AQ 开头的标准涉及多个领域,包括矿山、化工、烟花爆竹、金属冶炼、交通运输、机械制造等等。

这些标准对企业的安全生产管理、安全技术、设备设施、作业规程等方面提出了具体要求,旨在提高企业的安全生产能力和事故防范水平。

这些AQ开头的标准通常以国家安全生产监督管理总局的公告形式发布,并通过国家强制执行的方式实施。

同时,企业也可以通过采用这些标准来提高自身的安全生产水平,保障员工的安全和健康。

需要注意的是,AQ开头的标准并不是固定不变的,随着安全生产形势的变化和技术的不断进步,这些标准也会不断更新和完善。

因此,企业应该及时关注并采用最新的安全生产标准,以确保自身的安全生产工作符合法律法规和行业要求。

常用处方缩写词

常用处方缩写词常用处方缩写词q.d.(每日1次)b.i.d.(每日2次)t.i.d.(每日3次)q.i.d.(每日4次)q.h.(每小时)q.m.(每晨)q.n.(每晚)q.6h.(每六小时1次)q.2d(每二日1次)a.c.(饭前)p.c(饭后)h.s.(睡前)a.m.(上午)p.m.(下午)p.r.n.(必要时)s.o.s(需要时)star.!(立即)cato!(急速地)i.d.(皮内注射)i.h.(皮下注射)i.m.(肌内注射)i.v.(静脉注射)i.v.gtt.(静脉滴注)p.o.(口服)Rp.(取)co.(复方的)sig.或s.(用法)lent!(慢慢地)U(单位)IU(国际单位)Amp.(安瓿剂)Caps.(胶囊剂)Inj.(注射剂)Sol.(溶液剂)Tab.(片剂)Syr.(糖浆剂)Sig标记/用法处方缩写词列表是医学处方中常用的基于拉丁文术语的词头缩写。

其中的大写、句点'.'的使用是可选的版式风格。

列表中不包含处方中常见的药品的缩写。

列表中红色条目是在美国不建议使用,褐色条目是其他组织不建议使用。

cibummealsa.d. aurisdextra右耳right ear"a" can bemistaken asan "o" whichcould read"o.d.",meaningright eyead lib.adlibitum随意,任意量use asmuch asonedesires;freelyadmo v. admove用于applyagit agita stir/shakealt. h. alternishoris每隔1小时;每2小时everyotherhour也写作a.h.a.m.m . admanumedicaeat doctorshanda.m. antemeridiem上午morning,beforenoonamp 安瓿ampule amt 数量amount aq aqua 水watera.l., a.s. aurislaeva,aurissinistra左耳left ear"a" can bemistaken asan "o" whichcould read"o.s." or"o.l",meaning lefteyeA.T.C. 昼夜不停,24小aroundthe clock时连续a.u. aurisutraque双耳both ears"a" can bemistaken asan "o" whichcould read"o.u.",meaningboth eyesbis bis 两次twiceb.d./b.i.d. bis indie每天两次twicedailyB.M. 排便bowel movemen tBNF 英国国家药典BritishNationalFormularybol. bolus 大剂量给药(通as a largesingledose常是静脉注射)(usually intraveno usly)B.S. 血糖blood sugarB.S.A 体表面积bodysurfaceareasb.t. 就寝时间,临睡前bedtimemistaken for"b.i.d",meaningtwice dailyBUCC bucca颊内insidecheekcap., caps. capsula胶囊capsulec, c. cum 与...(常写作)with(usuallywrittenwith a baron top ofthe "c") cib. cibus 食物foodcc cumcibo与食物(也用作表示毫升)with food,(but alsocubiccentimetre)mistaken for"U",meaningunits; alsohas anambiguousmeaning;use "mL" or"milliliters"cf 与食物with foodcomp. 复方compoun dcr., crm 乳膏;霜剂creamCST 继续同样治疗ContinuesametreatmentD 或d 天,或者剂days ordosesambiguousmeaning,write out"days" or"doses"D5W 5%葡萄糖溶液dextrose5%solution(sometimes writtenas D5W)D5NS 含5%葡萄糖的生理盐水dextrose5% innormalsaline(0.9%)D.A.W . 按所写(医嘱)配药dispenseas written(i.e., nogenericsubstitution)dc, D/C, disc 中断或排出discontinue ordischargeambiguousmeaningdieb. alt. diebusalternis每隔一天;每2天everyother daydil. 稀释的dilutedisp. 配药dispersibl e or dispensediv. 分次...(服用)dividedL 分升deciliterd.t.d. dentur给予同剂give ofsuchdose sDTO 去味鴉片酊劑deodorized tinctureof opiumcan easily beconfusedwith "dilutedtincture ofopium,"which is1/25th thestrength ofdeodorizedtincture ofopium;deaths haveresulted dueto massiveelix. 酏剂elixire.m.p. exmodoprescripto按照指示,按处方处理asdirectedemuls . emulsum乳剂emulsionet et 并且andeod 每隔一天everyother dayex aq exaqua水中in waterfl., fld. 液fluidft. fiat 任其发生,顺其自然make; letit be madeg 克gram gr 格令graingtt(s) gutta(e)滴drop(s)H 皮,皮下注射hypodermich, hr hora 小时hourh.s. horasomni就寝时atbedtimeh.s 睡眠时或半强度hoursleep orhalf-strengthambiguousmeaningID 皮肤的intradermalIJ, inj injectio注射injectionmistaken for"IV",meaningintravenouslyIM 肌肉注射intramuscular (withrespect toinjections)IN 鼻内intranasal mistaken for "IM", meaning intramuscul ar, or "IV", meaning intravenousl yIP 腹膜内的intraperitonealIU 国际单位制en:international unitmistaken for"IV" or "10",spell out"international unit"IV 静脉intraveno治疗usIVP 静脉推注intravenous pushIVPB intraveno us piggybackkg 千克kilogramL.A.S. label as suchLCD 煤焦油coal tarsolutionlin linimentum搽剂linimentliq liquor溶液,液体solutionlot. 洗剂lotionMAE 活动四肢Moves AllExtremitiesmane mane 晨时in the morningM. misce混合mixm, min minimum最小值aminimummcg 微克en:microgramRecommendedreplacementfor "µg"which maybe confusedwith "mg"m.d.u. moredictoutendus按照指示使用to be usedasdirectedmEq 毫当量milliequivalentmg 毫克milligrammg/dL 毫克/分升milligrams perdeciliterMgSO 4 硫酸镁en:magnesiumsulfatemay beconfusedwith"MSO4",spell out"magnesiumsulfate"mist. mistura混合mixmitte mitte 发送send mL 毫升millilitreMS 硫酸吗啡或硫酸镁en:morphinesulfate oren:magnesiumsulfatecan meaneithermorphinesulfate ormagnesiumsulfate, spellout eitherMSO4 硫酸吗啡en:morphine sulfatemay beconfusedwith"MgSO4",spell out"morphinesulfate"nebul nebula喷雾 a sprayN.M.T. 不超过not morethannoct. nocte 夜里at nightnon rep. nonrepetatur不重复norepeatsNPO nilperos禁食,禁饮水nothingby mouthNS 生理normal盐水saline(0.9%)1/2NS 半浓度生理盐水halfnormalsaline(0.45%)N.T.E. 不超过not toexceedo_2 双眼both eyes, sometime s written as o2od omnein die每天everyday/oncedaily(preferredto qd inthe UK[2])od oculusdexte右眼right eye"o" can bemistaken asan "a" whichr could read"a.d.",meaningright ear,confusionwith omne indieom omnemane每天上午(晨时)everymorningon omnenocte每夜everynighto.p.d. 每天一次once perdayo.s. oculussinister左眼left eye"o" can bemistaken asan "a" whichcould read"a.s.",meaning leftearo.u. oculusuterque双眼both eyes"o" can bemistaken asan "a" whichcould read"a.u.",meaningboth earsoz 盎司en:ounceper per 经;通过by orthroughp.c. postcibum饭后aftermealspig./pi gm. pigmentum涂剂paintp.m. postmeridiem下午与晚上eveningorafternoonp.o. en:per os经口,口服by mouthor orallyp.r. perrectum经直肠by rectumPRN, prn en:pro renata按需as neededpulv. pulvis散剂powderPV pervaginam经阴道via thevaginaq quaque每,各 every, perq.a.d. quaquealternis die每隔一天everyother dayq.a.m. quaq每天every dayue die ante merid iem 午前beforenoonq.d.s. quater diesumendus每天四次four timesa daycan bemistaken for"qd" (everyday)q.p.m. quaquediepostmeridiem每天下午或每晚every dayafter noonor everyeveningq.h. quaquehora每小时everyhourq.h.s. quaquehora每夜就寝时everynight atbedtimesomn iq.1 h, q.1°quaque 1hora每小时(可用其它数字替换"1")every 1hour; (canreplace"1" withothernumbers)q.d., q1d quaquedie每天every daymistaken for"QOD" or"qds," spellout "everyday" or"daily"q.i.d. quater indie每天四次four timesa daycan bemistaken for"qd" or"qod," writeout "fourtimes a day"q4PM 下午4时at 4pmmistaken tomean everyfour hoursq.o.d. 每隔一天;每两天everyother daymistaken for"QD," spellout "everyother day"qqh quaterquaquehora每四小时every fourhoursq.s. quantumsufficiat足够量asufficientquantityQWK 每周every weekR 直肠rectalrep., rept. repetatur重复repeatsRL, R/L 乳酸林格氏液en:Ringer's lactates sine 没有...without(usuallywrittenwith a baron top ofthe "s")s.a. secundumartem按常规accordingto the art(acceptedpractice);use yourjudgementSC, subc,subcu t, subq, 皮下subcutaneous"SC" can bemistaken for"SL,"meaningsublingual;SQ "SQ" can bemistaken for"5Q"meaning fiveevery doses.i.d/S ID semel indie每天一次once adayusedexclusivelyin veterinarymedicinesig signa write on labelSL 舌下sublingua lly, under the tonguesol solutio溶液solutions.o.s., si op. sit siopussit需要时if there isa needss semi one half mistaken fors or slidingscale"55" or "1/2"SSI, SSRI slidingscaleinsulin orslidingscaleregular en:insulinmistaken tomean"strong en:solution of en:iodine" or"en:selectiveserotoninreuptakeinhibitor"SNRI (antid epres sant) 5-羟色胺/去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(抗抑郁)Serotonin–norepinephrinereuptakeinhibitorSSRI (antid epres sant) 抗抑郁的选择性5-羟色胺再吸收抑制剂selectiveserotoninreuptakeinhibitor(a specificclass ofantidepressant)stat statim立即immediatelySubQ 皮下subcutan eouslysupp suppositorium栓剂en:suppositorysusp 混悬剂suspensionsyr syrupus糖浆剂syruptab tabell片剂tabletatal., t talus suchtbsp汤匙en:tables poontrochetrochiscus锭剂 lozenget.d.s.terdiesume ndum每天三次 three times a dayt.i.d.ter in die每天三次 three times a dayt.i.w.每周三次 three times a week mistaken for twice a weektop.局部的 topicalT.P.N.全肠外营en:totalparenteral养nutrition tr,tinc.,tinct.酊剂tincturetsp 1茶匙(约5毫升)en:teaspoonU 度量单位unitmistaken fora "4", "0" or"cc", spellout "unit"u.d., ut. dict. utdictum作为指示asdirectedung. unguentum软膏ointmentU.S.P. 美国药典en:UnitedStatesPharmacopoeiavag 阴道的vaginallyw 与withw/a 醒时while awakewf 与食物with food(withmeals)w/o 没有...withoutX 次数times Y.O. 年龄years oldμg微克en:microgrammistaken for"mg",meaning en:milligram。

需求函数公式

需求函数公式需求函数是指用来描述消费者对某种商品或服务需求的数学函数。

它通常用来表示消费者的需求量如何随着价格、收入和其他相关因素的变化而变化。

需求函数的公式可以根据具体的情况和经济模型来确定,下面是一些相关参考内容。

一、线性需求函数:线性需求函数是最简单直接的一种需求函数形式,它假设需求量与价格成反比。

线性需求函数的一般形式可以表示为:Q =a - bP其中Q表示需求量,P表示价格,a和b为常数。

a表示需求函数的截距,表示当价格为0时的需求量;b表示负的斜率,表示需求量随价格变化的速度。

二、非线性需求函数:非线性需求函数是指需求量与价格的关系不是简单的线性关系,而是形成了一条曲线。

常见的非线性需求函数包括:1.常见的例子有二次函数需求函数形式:Q = a - bP + cP^2其中a、b、c为常数,P表示价格,Q表示需求量。

二次函数形式的需求函数在价格变化时呈现出一种曲线的关系。

2.指数函数需求函数形式:Q = aP^b其中a和b为常数,P表示价格,Q表示需求量。

指数函数形式的需求函数在价格变化时呈现出一种指数增长或指数衰减的关系。

三、多变量需求函数:多变量需求函数考虑了除了价格之外的其他影响因素对需求量的影响。

常见的多变量需求函数包括:1.收入影响的需求函数形式:Q = a + bP + cY其中Q表示需求量,P表示价格,Y表示收入,a、b、c为常数。

这种需求函数考虑了收入对需求量的影响,可以用来分析在不同收入水平下的需求量变化。

2.广义线性需求函数形式:Q = a + b1P + b2I + b3A + b4O +b5T其中Q表示需求量,P表示价格,I表示收入,A表示广告投入, O表示其他相关因素(如季节性因素),T表示时间,a,b1,b2,b3,b4, b5为常数。

这种需求函数考虑了多种影响因素对需求量的影响,可以用来分析需求量如何受到多种因素的共同影响。

以上是一些关于需求函数公式的参考内容。

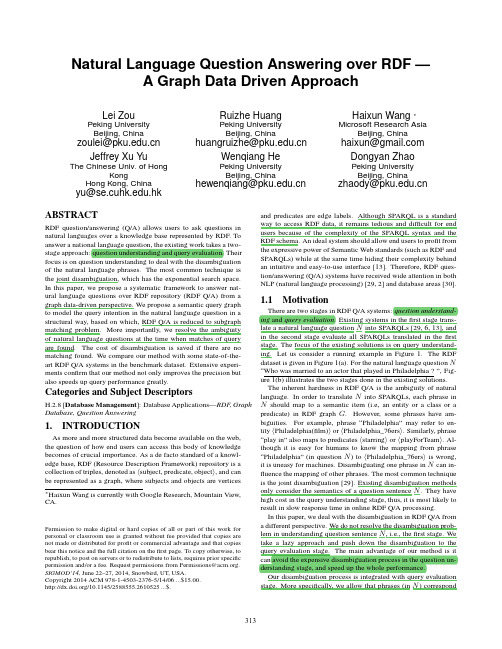

3 Natural Language Question Answering over RDF - A Graph Data Driven Approach

Natural Language Question Answering over RDF — A Graph Data Driven ApproachLei ZouPeking University Beijing, ChinaRuizhe HuangPeking University Beijing, ChinaHaixun Wang ∗Microsoft Research Asia Beijing, Chinazoulei@ Jeffrey Xu YuThe Chinese Univ. of Hong Kong Hong Kong, Chinahuangruizhe@ Wenqiang HePeking University Beijing, Chinahaixun@ Dongyan ZhaoPeking University Beijing, Chinayu@.hk ABSTRACThewenqiang@zhaody@RDF question/answering (Q/A) allows users to ask questions in natural languages over a knowledge base represented by RDF. To answer a national language question, the existing work takes a twostage approach: question understanding and query evaluation. Their focus is on question understanding to deal with the disambiguation of the natural language phrases. The most common technique is the joint disambiguation, which has the exponential search space. In this paper, we propose a systematic framework to answer natural language questions over RDF repository (RDF Q/A) from a graph data-driven perspective. We propose a semantic query graph to model the query intention in the natural language question in a structural way, based on which, RDF Q/A is reduced to subgraph matching problem. More importantly, we resolve the ambiguity of natural language questions at the time when matches of query are found. The cost of disambiguation is saved if there are no matching found. We compare our method with some state-of-theart RDF Q/A systems in the benchmark dataset. Extensive experiments confirm that our method not only improves the precision but also speeds up query performance greatly.and predicates are edge labels. Although SPARQL is a standard way to access RDF data, it remains tedious and difficult for end users because of the complexity of the SPARQL syntax and the RDF schema. An ideal system should allow end users to profit from the expressive power of Semantic Web standards (such as RDF and SPARQLs) while at the same time hiding their complexity behind an intuitive and easy-to-use interface [13]. Therefore, RDF question/answering (Q/A) systems have received wide attention in both NLP (natural language processing) [29, 2] and database areas [30].1.1MotivationCategories and Subject DescriptorsH.2.8 [Database Management]: Database Applications—RDF, Graph Database, Question Answering1.INTRODUCTIONAs more and more structured data become available on the web, the question of how end users can access this body of knowledge becomes of crucial importance. As a de facto standard of a knowledge base, RDF (Resource Description Framework) repository is a collection of triples, denoted as subject, predicate, object , and can be represented as a graph, where subjects and objects are vertices∗ Haixun Wang is currently with Google Research, Mountain View, CA.Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from Permissions@. SIGMOD’14, June 22–27, 2014, Snowbird, UT, USA. Copyright 2014 ACM 978-1-4503-2376-5/14/06 ...$15.00. /10.1145/2588555.2610525 ...$.There are two stages in RDF Q/A systems: question understanding and query evaluation. Existing systems in the first stage translate a natural language question N into SPARQLs [29, 6, 13], and in the second stage evaluate all SPARQLs translated in the first stage. The focus of the existing solutions is on query understanding. Let us consider a running example in Figure 1. The RDF dataset is given in Figure 1(a). For the natural language question N “Who was married to an actor that played in Philadelphia ? ”, Figure 1(b) illustrates the two stages done in the existing solutions. The inherent hardness in RDF Q/A is the ambiguity of natural language. In order to translate N into SPARQLs, each phrase in N should map to a semantic item (i.e, an entity or a class or a predicate) in RDF graph G. However, some phrases have ambiguities. For example, phrase “Philadelphia” may refer to entity Philadelphia(film) or Philadelphia_76ers . Similarly, phrase “play in” also maps to predicates starring or playForTeam . Although it is easy for humans to know the mapping from phrase “Philadelphia” (in question N ) to Philadelphia_76ers is wrong, it is uneasy for machines. Disambiguating one phrase in N can influence the mapping of other phrases. The most common technique is the joint disambiguation [29]. Existing disambiguation methods only consider the semantics of a question sentence N . They have high cost in the query understanding stage, thus, it is most likely to result in slow response time in online RDF Q/A processing. In this paper, we deal with the disambiguation in RDF Q/A from a different perspective. We do not resolve the disambiguation problem in understanding question sentence N , i.e., the first stage. We take a lazy approach and push down the disambiguation to the query evaluation stage. The main advantage of our method is it can avoid the expensive disambiguation process in the question understanding stage, and speed up the whole performance. Our disambiguation process is integrated with query evaluation stage. More specifically, we allow that phrases (in N ) correspond313Subject Antonio_Banderas Antonio_Banderas Antonio_Banderas Philadelphia_(film) Jonathan_Demme Philadelphia Aaron_McKie James_Anderson Constantin_Stanislavski Philadelphia_76ers An_Actor_Prepares c1 actor <type> u2 Antonio_Banderas <starring> <spouse> u1 Melanie_Griffith c2Predicate type spouse starring type director type bornIn create type type c3Object actor Melanie_Griffith Philadelphia_(film) film Philadelphia_(film) city Philadelphia An_Actor_Prepares Basketball_team Book Philadelphia city actor play in Disambiguation be married to SPARQL GenerationWho was married to an actor that play in Philadelphia ? Generating a Semantic Query Graph <spouse> <actor> <An_Actor_Prepares> <starring> <playedForTeam> <Philadelphia> <Philadelphia(film)> <Philadelphia_76ers> ?who v1 Who be married to “that” v2 play in actor <spouse, 1.0> <playForTeam, 1.0> <actor, 1.0> <Philadelphia, 1.0> <starring, 0.9> <Philadelphia(film), 0.9> <An_Actor_Prepares, 0.9> <director, 0.5> <Philadelphia_76ers, 0.8> Philadelphia v3 Semantic Query GraphplayedForTeam Philadelphia_76ersfilm <type> u3 Philadelphia_(film) <director> u4 Jonathan_Demme <type> u5 Philadelphia <bornIn > u6 Aaron_McKie c4 Basketball_team <type>SELECT ?y WHERE { ?x starring Philadelphia_ ( film ) . ?x type actor . ?x spouse ?y. } Query EvaluationFinding Top-k Subgraph Matches c1 actor u2 <spouse> u1 Melanie_Griffith <type> Antonio_Banderasu7 James_Anderson<playedForTeam>u10 Philadelphia_76ers u8 c5 Book Constantin_Stanislavski <create> <type> u10 An_Actor_Prepares (a) RDF Dataset and RDF GraphSPARQL Query Engine<starring> u3 Philadelphia_(film)?y: Melanie_Griffith (b) SPARQL Generation-and-Query Framework(c) Our FrameworkFigure 1: Question Answering Over RDF Dataset to multiple semantic items (e.g., subjects, objects and predicates) in RDF graph G in the question understanding stage, and resolve the ambiguity at the time when matches of the query are found. The cost of disambiguation is saved if there are no matching found. In our problem, the key problem is how to define a “match” of question N in RDF graph G and how to find matches efficiently. Intuitively, a match is a subgraph (of RDF graph G) that can fit the semantics of question N . The formal definition of the match is given in Definition 3 (Section 2). We illustrate the intuition of our method by an example. Consider a subgraph of graph G in Figure 1(a) (the subgraph induced → by vertices u1 , u2 , u3 and c1 ). Edge − u− 2 c1 says that “Antonio Ban− − → deras is an actor”. Edge u2 u1 says that “Melanie Griffith is mar→ ried to Antonio Banderas”. Edge − u− 2 u3 says that “Antonio Banderas starred in a film Philadelphia(film) ”. The natural language question N is “Who was married to an actor that played in Philadel→ − − → phia”. Obviously, the subgraph formed by edges − u− 2 c1 , u2 u1 and − − → u2 u3 is a match of N . “Melanie Griffith” is a correct answer. On the other hand, we cannot find a match (of N ) containing Philadelphia _76ers in RDF graph G. Therefore, the phrase “Philadelphia” (in N ) cannot map to Philadelphia_76ers . This is the basic idea of our data-driven approach. Different from traditional approaches, we resolve the ambiguity problem in the query evaluation stage. A challenge of our method is how to define a “match” between a subgraph of G and a natural language question N . Because N is unstructured data and G is graph structure data, we should fill the gap between two kinds of data. Therefore, we propose a semantic query graph QS to represent the question semantics of N . We formally define QS in Definition 2. An example of QS is given in Figure 1(c), which represents the semantic of the question N . Each edge in QS denotes a semantic relation. For example, edge v1 v2 denotes that “who was married to an actor”. Intuitively, a match of question N over RDF graph G is a subgraph match of QS over G (formally defined in Definition 3). N . The coarse-grained framework is given in Figure 1(c). In the question understanding stage, we interpret a natural language question N as a semantic query graph QS (see Definition 2). Each edge in QS denotes a semantic relation extracted from N . A semantic relation is a triple rel,arg 1,arg 2 , where rel is a relation phrase, and arg 1 and arg 2 are its associated arguments. For example, “play in”,“actor”,“Philadelphia” is a semantic relation. The edge label is the relation phrase and the vertex labels are the associated arguments. In QS , two edges share one common endpoint if the two corresponding relations share one common argument. For example, there are two extracted semantic relations in N , thus, we have two edges in QS . Although they do not share any argument, arguments “actor” and “that” refer to the same thing. This phenomenon is known as “coreference resolution” [25]. The phrases in edges and vertices of QS can map to multiple semantic items (such as entities, classes and predicates) in RDF graph G. We allow the ambiguity in this stage. For example, the relation phrase “play in” (in edge v2 v3 ) corresponds to three different predicates. The argument “Philadelphia” in v3 also maps to three different entities, as shown in Figure 1(c). In the query evaluation stage, we find subgraph matches of QS over RDF graph G. For each subgraph match, we define its matching score (see Definition 6) that is based on the semantic similarity of the matching vertices and edge in QS and the subgraph match in G. We find the top-k subgraph matches with the largest scores. For example, the subgraph induced by u1 , u2 and u3 matches query QS , as shown in Figure 1(c). u2 matches v2 (“actor”), since u2 ( Antonio_Banderas ) is a type-constraint entity and u2 ’s type is actor . u3 ( Philadelphia(film) ) matches v3 (“Philadelphia”) and u1 ( Melanie_Griffith ) matches v1 (“who”). The result to question N is Melanie_Griffith . Also based on the subgraph match query, we cannot find a subgraph containing u10 ( Philadelphia_76ers ) to match QS . It means that the mapping from “Philadelphia” to u10 is a false alarm. We deal with disambiguation in query evaluation based on the matching result. Pushing down disambiguation to the query evaluation stage not only improves the precision but also speeds up the whole query response time. Take the up-to-date DEANNA [20] as an example. DEANNA [29] proposes a joint disambiguation technique. It mod-1.2Our ApproachAlthough there are still two stages “question understanding” and “query evaluation” in our method, we do not adopt the existing framework, i.e., SPARQL generation-and-evaluation. We propose a graph data-driven solution to answer a natural language question314Table 1: NotationsNotation G(V, E ) N Q Y D T rel vi /ui Cvi /Cvi vj d Definition and Description RDF graph and vertex and edge sets A natural language question A SPARQL query The dependency tree of qN L The paraphrase dictionary A relation phrase dictionary A relation phrase A vertex in query graph/RDF graph Candidate mappings of vertex vi /edge vi vj Candidate mappings of vertex vi /edge vi vjĂĂFigure 3: Paraphrase Dictionary D Philadelphia(film) and Philadelphia_76ers . We need to know which one is users’ concern. In order to address the first challenge, we extract the semantic relations (Definition 1) implied by the question N , based on which, we build a semantic query graph QS (Definition 2) to model the query intention in N . D EFINITION 1. (Semantic Relation). A semantic relation is a triple rel, arg 1, arg 2 , where rel is a relation phrase in the paraphrase dictionary D, arg 1 and arg 2 are the two argument phrases. In the running example, “be married to”, “who”,“actor” is a semantic relation, in which “be married to” is a relation phrase, “who” and “actor” are its associated arguments. We can also find another semantic relation “play in”, “that”,“Philadelphia” in N . D EFINITION 2. (Semantic Query Graph) A semantic query graph is denoted as QS , in which each vertex vi is associated with an argument and each edge vi vj is associated with a relation phrase, 1 ≤ i, j ≤ |V (QS )| . Actually, each edge in QS together with the two endpoints represents a semantic relation. We build a semantic query graph QS as follows. We extract all semantic relations in N , each of which corresponds to an edge in QS . If the two semantic relations have one common argument, they share one endpoint in QS . In the running example, we get two semantic relations, i.e., “be married to”, “who”,“actor” and “play in”, “that”,“Philadelphia” , as shown in Figure 2. Although they do not share any argument, arguments “actor” and “that” refer to the same thing. This phenomenon is known as “coreference resolution” [25]. Therefore, the two edges also share one common vertex in QS (see Figure 2(c)). We will discuss more technical issues in Section 4.1. To deal with the ambiguity issue (the second challenge), we propose a data-driven approach. The basic idea is: for a candidate mapping from a phrase in N to an entity (i.e., vertex) in RDF graph G, if we can find the subgraph containing the entity that fits the query intention in N , the candidate mapping is correct; otherwise, this is a false positive mapping. To enable this, we combine the disambiguation with the query evaluation in a single step. For example, although “Philadelphia” can map three different entities, in the query evaluation stage, we can only find a subgraph containing Philadelphia_film that matches the semantic query graph QS . Note that QS is a structural representation of the query intention in N . The match is based on the subgraph isomorphism between QS and RDF graph G. The formal definition of match is given in Definition 3. For the running example, we cannot find any subgraph match containing Philadelphia or Philadelphia_76ers of QS . The answer to question N is “Melanie_Griffith” according to the resulting subgraph match. Generally speaking, there are offline and online phases in our solution.els the disambiguation as an ILP (integer liner programming) problem, which is an NP-hard problem. To enable the disambiguation, DEANNA needs to build a disambiguation graph. Some phrases in the natural language question map to some candidate entities or predicates in RDF graph as vertices. In order to introduce the edges in the disambiguation graph, DEANNA needs to compute the pairwise similarity and semantic coherence between every two candidates on the fly. It is very costly. However, our method avoids the complex disambiguation algorithms, and combines the query evaluation and the disambiguation in a single step. We can speed up the whole performance greatly. In a nutshell, we make the following contributions in this paper. 1. We propose a systematic framework (see Section 2) to answer natural language questions over RDF repositories from a graph data-driven perspective. To address the ambiguity issue, different from existing methods, we combine the query evaluation and the disambiguation in a single step, which not only improves the precision but also speed up query processing time greatly. 2. In the offline processing, we propose a graph mining algorithm to map natural language phrases to top-k possible predicates (in a RDF dataset) to form a paraphrase dictionary D, which is used for question understanding in RDF Q/A. 3. In the online processing, we adopt two-stage approach. In the query understanding stage, we propose a semantic query graph QS to represent the users’ query intention and allow the ambiguity of phrases. Then, we reduce RDF Q/A into finding subgraph matches of QS over RDF graph G in the query evaluation stage. We resolve the ambiguity at the time when matches of the query are found. The cost of disambiguation is saved if there are no matching found. 4. We conduct extensive experiments over several real RDF datasets (including QALD benchmark) and compare our system with some state-of-the-art systems. Experiment results show that our solution is not only more effective but also more efficient.2.FRAMEWORKThe problem to be addressed in this paper is to find the answers to a natural language question N over an RDF graph G. Table 1 lists the notations used throughout this paper. There are two key challenges in this problem. The first one is how to represent the query intention of the natural language question N in a structural way. The underlying RDF repository is a graph structured data, but, the natural language question N is unstructured data. To enable query processing, we need a graph representation of N . The second one is how to address the ambiguity of natural language phrases in N . In the running example, “Philadelphia” in the question N may refer to different entities, such as315(a) Natural Language Question1 Who actor 23 1 2 3(b) Semantic Relations Extraction and Building Semantic Query Graph3 5 2?who <spouse, 1.0> 1 <actor, 1.0> 7469 8An_Actor_Prepares5 10Figure 2: Natural Language Question Answering over Large RDF Graphs2.1OfflineTo enable the semantic relation extraction from N , we build a paraphrase dictionary D, which records the semantic equivalence between relation phrases and predicates. For example, in the running example, natural language phrases “be married to” and “play in” have the similar semantics with predicates spouse and starring , respectively. Some existing systems, such as Patty [18] and ReVerb [10], provide a rich relation phrase dataset. For each relation phrase, they also provide a support set with entity pairs, such as ( Antonio_Banderas , Philadelphia(film) ) for the relation phrase “play in”. Table 2 shows two sample relation phrases and their supporting entity pairs. The intuition of our method is as follows: for each relation phrase reli , let Sup(reli ) denotes a set of supporting entity pairs. We assume that these entity pairs also occur in RDF graph. Experiments show that more than 67% entity pairs in the Patty relation phrase dataset occur in DBpedia RDF graph. The frequent predicates (or predicate paths) connecting the entity pairs in Sup(reli ) have the semantic equivalence with the relation phrase reli . Based on this idea, we propose a graph mining algorithm to find the semantic equivalence between relation phrases and predicates (or predicate paths).2.2OnlineThere are two stages in RDF Q/A: question understanding and query evaluation. 1) Question Understanding. The goal of the question understanding in our method is to build a semantic query graph QS for representing users’ query intention in N . We first apply Stanford Parser to N to obtain the dependency tree Y of N . Then, we extract the semantic relations from Y based on the paraphrase dictionary D. The basic idea is to find a minimum subtree (of Y ) that contains all words of rel, where rel is a relation phrase in D. The subtree is called an embedding of rel in Y . Based on the embedding position in Y , we also find the associated arguments according to some linguistics rules. The relation phrase rel together with the two associated arguments form a semantic relation, denoted as a triple rel,arg 1,arg 2 . Finally, we build a semantic query graphQS by connecting these semantic relations. We will discuss more technical issues in Section 4.1. 2) Query Evaluation. As mentioned earlier, a semantic query graph QS is a structural representation of N . In order to answer N , we need to find a subgraph (in RDF graph G) that matches QS . The match is defined according to the subgraph isomorphism (formally defined in Definition 3) First, each argument in vertex vi of QS is mapped to some entities or classes in the RDF graph. Given an argument argi (in vertex vi of QS ) and an RDF graph G, entity linking [31] is to retrieve all entities and classes (in G) that possibly correspond to argi , denoted as Cvi . Each item in Cvi is associated with a confidence probability. In Figure 2, argument “Philadelphia” is mapped to three different entities Philadelphia , Philadelphia(film) and Philadelphia_76ers , while argument “actor” is mapped to a class Actor and an entity An_ Actor_Prepares . We can distinguish a class vertex and an entity vertex according to RDF’s syntax. If a vertex has an incoming adjacent edge with predicate rdf:type or rdf:subclass , it is a class vertex; otherwise, it is an entity vertex. Furthermore, if arg is a wh-word, we assume that it can match all entities and classes in G. Therefore, for each vertex vi in QS , it also has a ranked list Cvi containing candidate entities or classes. Each relation phrase relvi vj (in edge vi vj of QS ) is mapped to a list of candidate predicates and predicate paths. This list is denoted as Cvi vj . The candidates in the list are ranked by the confidence probabilities. It is important to note that we do not resolve the ambiguity issue in this step. For example, we allow that “Philadelphia” maps to three possible entities, Philadelphia_76ers , Philadelphia and Philadelphia(film) . We push down the disambiguation to the query evaluation step. Second, if a subgraph in RDF graph can match QS if and only if the structure (of the subgraph) is isomorphism to QS . We have the following definition about match. D EFINITION 3. (Match) Consider a semantic query graph QS with n vertices {v1 ,...,vn }. Each vertex vi has a candidate list Cvi , i = 1, ..., n. Each edge vi vj also has a candidate list of Cvi vj ,316Joseph_P._Kennedy,_Sr.Table 2: Relation Phrases and Supporting Entity PairsRelation Phrase “play in” “uncle of” ( ( ( ( Supporting Entity Pairs Antonio_Banderas , Philadelphia(film) ), Julia_Roberts , Runaway_Bride ),...... Ted_Kennedy , John_F._Kennedy,_Jr. ) Peter_Corr , Jim_Corr ),......Antonio_BanderashasChildTed_KennedyhasChildJohn_F._KennedyhasChild hasGenderMale John_F._Kennedy,_Jr.starringPhiladelphia(film) (a) Āplay ināwhere 1 ≤ i = j ≤ n. A subgraph M containing n vertices {u1 ,...,un } in RDF graph G is a match of QS if and only if the following conditions hold: 1. If vi is mapping to an entity ui , i = 1, ..., n, ui must be in list Cvi ; and 2. If vi is mapping to a class ci , i = 1, ..., n, ui is an entity whose type is ci (i.e., there is a triple ui rdf:type ci in RDF graph) and ci must be in Cvi ; and → − − → u− 3. ∀vi vj ∈ QS ; − i uj ∈ G ∨ uj ui ∈ G. Furthermore, the − → − − → predicate Pij associated with u− i uj (or uj ui ) is in Cvi vj , 1 ≤ i, j ≤ n. Each subgraph match has a score, which is derived from the probability confidences of each edge and vertex mapping. Definition 6 defines the score, which we will discuss later. Our goal is to find all subgraph matches with the top-k scores. A TA-style algorithm [11] is proposed in Section 4.2.2 to address this issue. Each subgraph match of QS implies an answer to the natural language question N , meanwhile, the ambiguity is resolved. For example, in Figure 2, although “Philadelphia” can map three different entities, in the query evaluation stage, we can only find a subgraph (included by vertices u1 , u2 , u3 and c1 in G) containing Philadelphia_film that matches the semantic query graph QS . According to the subgraph graph, we know that the result is “Melanie_Griffith”, meanwhile, the ambiguity is resolved. Mapping phrases “Philadelphia” to Philadelphia or Philadelphia_76ers of QS is false positive for the question N , since there is no data to support that.hasGender(b) Āuncle ofāFigure 4: Mapping Relation Phrases to Predicates or Predicate Paths Although mapping these relation phrases into canonicalized representations is the core challenge in relation extraction [17], none of the prior approaches consider mapping a relation phrase to a sequence of consecutive predicate edges in RDF graph. Patty demo [17] only finds the equivalence between a relation phrase and a single predicate. However, some relation phrases cannot be interpreted as a single predicate. For example, “uncle of” corresponds to a length-3 predicate path in RDF graph G, as shown in Figure 3. In order to address this issue, we propose the following approach. Given a relation phrase reli , its corresponding support set containing entity pairs that occurs in RDF graph is denoted as Sup(reli ) j 1 m = { (vi , vi1 ), ..., (vi , vim )}. Considering each pair (vi , vij ), j j j = 1, ..., m, we find all simple paths between vi and vi in RDF j graph G, denoted as P ath(vi , vij ). Let P S (reli ) = j =1,...,m j j P ath(vi , vi ). For example, given an entity pair ( Ted_Kennedy , John_F._Kennedy,_Jr. ), we locate them at RDF graph G and find simple pathes between them (as shown in Figure 4). If a path L is frequent in P S (“uncle of”), L is a good candidate to represent the semantic of relation phrase “uncle of”. For efficiency considerations, we only find simple paths with no longer than a threshold1 . We adopt a bi-directional BFS (breathj j first-search) search from vertices vi and vij to find P ath(vi , vij ). Note that we ignore edge directions (in RDF graph) in a BFS process. For each relation phrase reli with m supporting entity pairs, j we have a collection of all path sets P ath(vi , vij ), denoted as j j P S (reli ) = j =1,...,m P ath(vi , vi ). Intuitively, if a predicate path is frequent in P S (reli ), it is a good candidate that has semantic equivalence with relation phrase reli . However, the above simple intuition may introduce noises. For example, we find that (hasGender , hasGender) is the most frequent predicate path in P S (“uncle of”) (as shown in Figure 4). Obviously, it is not a good predicate path to represent the sematic of relation phrase “uncle of”. In order to eliminate noises, we borrow the intuition of tf-idf measure [15]. Although (hasGender ,hasGender) is frequent in P S (“uncle of”), it is also frequent in the path sets of other relation phrases, such as P S (“is parent of”), P S (“is advisor of”) and so on. Thus, (hasGender ,hasGender) is not an important feature for P S (“uncle of”). It is exactly the same with measuring the importance of a word w with regard to a document. For example, if a word w is frequent in lots of documents in a corpus, it is not a good feature. A word has a high tf-idf, a numerical statistic in measuring how important a word is to a document in a corpus, if it occurs in a document frequently, but the frequency of the word in the whole corpus is small. In our problem, for each relation phrase reli , i = 1, ..., n, we deem P S (reli ) as a virtual document. All predicate paths in P S (reli ) are regarded as virtual words. The corpus contains all P S (reli ), i = 1, ..., n. Formally, we define tf-idf value of a predicate path L in the following definition. Note that if L is a length-1 predicate path, L is a predicate P .1 We set the threshold as 4 in our experiments. More details about the parameter setting will be discussed in Section 6.3.OFFLINEThe semantic relation extraction relies on a paraphrase dictionary D. A relation phrase is a surface string that occurs between a pair of entities in a sentence [17], such as “be married to” and “play in” in the running example. We need to build a paraphrase dictionary D, such as Figure 3, to map relation phrases to some candidate predicates or predicate paths. Table 2 shows two sample relation phrases and their supporting entity pairs. In this paper, we do not discuss how to extract relation phrases along with their corresponding entity pairs. Lots of NLP literature about relation extraction study this problem, such as Patty [18] and ReVerb [10]. For example, Patty [18] utilizes the dependency structure in sentences and ReVerb [10] adopts the n-gram to find relation phrases and the corresponding support set. In this work, we assume that the relation phrases and their support sets are given. The task in the offline processing is to find the semantic equivalence between relation phrases and the corresponding predicates (and predicate paths) in RDF graphs, i.e., building a paraphrase dictionary D like Figure 3. Suppose that we have a dictionary T = {rel1 , ..., reln }, where each reli is a relation phrase, i = 1, ..., n. Each reli has a support set of entity pairs that occur in RDF graph, i.e., Sup (reli ) 1 m = { (vi , vi1 ), ..., (vi , vim )}. For each reli , i = 1, ..., n, the goal is to mine top-k possible predicates or predicate paths formed by consecutive predicate edges in RDF graph, which have sematic equivalence with relation phrase reli .317。

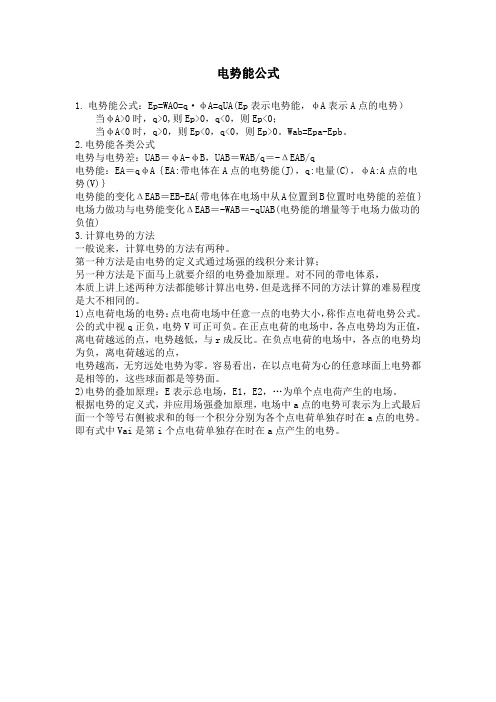

电势能公式

电势能公式1.电势能公式:Ep=WAO=q·φA=qUA(Ep表示电势能,φA表示A点的电势)当φA>0时,q>0,则Ep>0,q<0,则Ep<0;当φA<0时,q>0,则Ep<0,q<0,则Ep>0。

Wab=Epa-Epb。

2.电势能各类公式电势与电势差:UAB=φA-φB,UAB=WAB/q=-ΔEAB/q电势能:EA=qφA{EA:带电体在A点的电势能(J),q:电量(C),φA:A点的电势(V)}电势能的变化ΔEAB=EB-EA{带电体在电场中从A位置到B位置时电势能的差值}电场力做功与电势能变化ΔEAB=-WAB=-qUAB(电势能的增量等于电场力做功的负值)3.计算电势的方法一般说来,计算电势的方法有两种。

第一种方法是由电势的定义式通过场强的线积分来计算;另一种方法是下面马上就要介绍的电势叠加原理。

对不同的带电体系,本质上讲上述两种方法都能够计算出电势,但是选择不同的方法计算的难易程度是大不相同的。

1)点电荷电场的电势:点电荷电场中任意一点的电势大小,称作点电荷电势公式。

公的式中视q正负,电势V可正可负。

在正点电荷的电场中,各点电势均为正值,离电荷越远的点,电势越低,与r成反比。

在负点电荷的电场中,各点的电势均为负,离电荷越远的点,电势越高,无穷远处电势为零。

容易看出,在以点电荷为心的任意球面上电势都是相等的,这些球面都是等势面。

2)电势的叠加原理:E表示总电场,E1,E2,…为单个点电荷产生的电场。

根据电势的定义式,并应用场强叠加原理,电场中a点的电势可表示为上式最后面一个等号右侧被求和的每一个积分分别为各个点电荷单独存时在a点的电势。

即有式中Vai是第i个点电荷单独存在时在a点产生的电势。

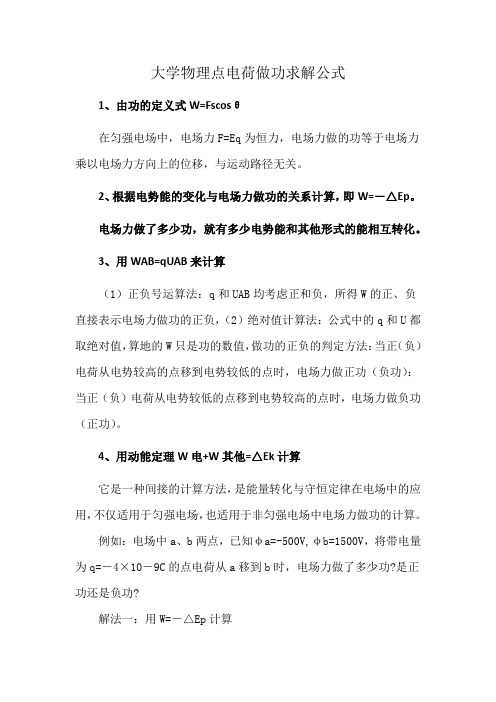

大学物理点电荷做功求解公式

大学物理点电荷做功求解公式1、由功的定义式W=Fscosθ在匀强电场中,电场力F=Eq为恒力,电场力做的功等于电场力乘以电场力方向上的位移,与运动路径无关。

2、根据电势能的变化与电场力做功的关系计算,即W=-△Ep。

电场力做了多少功,就有多少电势能和其他形式的能相互转化。

3、用WAB=qUAB来计算(1)正负号运算法:q和UAB均考虑正和负,所得W的正、负直接表示电场力做功的正负,(2)绝对值计算法:公式中的q和U都取绝对值,算地的W只是功的数值,做功的正负的判定方法:当正(负)电荷从电势较高的点移到电势较低的点时,电场力做正功(负功):当正(负)电荷从电势较低的点移到电势较高的点时,电场力做负功(正功)。

4、用动能定理W电+W其他=△Ek计算它是一种间接的计算方法,是能量转化与守恒定律在电场中的应用,不仅适用于匀强电场,也适用于非匀强电场中电场力做功的计算。

例如:电场中a、b两点,已知φa=-500V,φb=1500V,将带电量为q=-4×10-9C的点电荷从a移到b时,电场力做了多少功?是正功还是负功?解法一:用W=-△Ep计算电荷在a、b处的电势能分别为:Ea=qφa=(-4×10-9)×(-500)J=2×10-6JEb=qφb=-6×10-6J现从a到b,由W=-△Ep得W=-(Eb-Ea)=8×10-6J,W>0,表示电场力做正功解法二:用WAB=qUAB计算1.带符号运算:从a到b,Wab=qUab=q(φa-φb)=(-4×10-9)×(-500-1500)J=8×10-6J因为W>0,所以电场力做正功2.取绝对值进行计算:W=qU=4×10-9×2000J=8×10-6J(注意符号仅为数值).因为是负电荷从电势低处移至电势高处,所以电场力做正功。

Sequence analysis and gene content of PMTV RNA 3

Scottish Crop Research Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, United Kingdom; and *Department of Biological Sciences, University of Dundee DD 1 4HN, United Kingdom Received July 6, 1994; accepted September 301 1994

The complete sequence of the 2315 nucleotides in RNA 3 of potato mop-top furovirus (PMTV) isolate T was obtained by analysis of cDNA clones and by direct RNA sequencing. The sequence contains an open reading frame for the coat protein (2OK)terminated by an amber codon, followed by an in-phase coding region for an additional 47K. PMTV therefore resembles soil-borne wheat mosaic (SBWMV) and beet necrotic yellow vein (BNYVV) viruses (two other fungus4ransmitted viruses with rod-shaped particles) in having a coat protein-readthrough product. Comparison of the 3' untranslated regio

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Q.A & Q.C必备常识--验货流程

一.检验准备:

1.在业务联系表出来后,了解生产时间/进度,初步安排检验的时间。

2.提前了解生产的工厂,生产的品种,了解合同的大致内容,熟悉生产要求和我司的质量要求,熟悉检验标准,要求和检验的重点。

3.了解大致要求后,要对所验的货物主要有哪些疵点,要做到心中有数。

对容易出现的问题要重点抓住,要有灵活应变的处理方法,在验货时要做到认真细致。

4.了解大货出来的时间,并安排准时到达工厂。

5.准备好检验的必备仪器(卷尺,密度仪,计算器等)和检验表格(具体评分表,重点项目评分表,总表)

以及自己所需的生活用品。

二.执行检验:

1.到厂后,与工厂联系人初步的接触,了解工厂的概况,包括体制,建厂时间,工人人数,机台情况,工厂效益情况等。

特别留意质量控制情况,要求他们对质量的重视,要严格检验。

与检验的人员初步沟通,大致了解一下工厂的人事状况,如:成品部,质检部以及生产的负责人等。

2.到工厂检验车间观看工厂检验员的检验,了解工厂的检验严格与否,并了解工厂的检验依据,检验制度,以及对一些严重的疵点的处理方法;同时也可到生产车间,了解我司货物的生产情况等问题,做到心中有数。

3.落实检验场所(如检验平台),设备(如克重机器,卷尺,计算器等)。

4.通常情况下应先征求工厂的意见和安排检验。

5.在检验时,我们应要求工厂的人进行配合,以便更好的操作。

6.确定检验的数量:

A.一般情况下,是要根据不同的款号数量,随机抽查10-20%。

B.对抽取的货物进行严格检验,如最终质量合格,那就停止检验,示整批货物为合格;若出现有少许的或接近或超过评分标准,那就必须对余下的货物进行再抽验10%,若后面的质量合格,那我们就将前面的不合格的货全部降等;当然,同样后面的质量仍不合格,那就示整批货物为不合格。

7.抽验的操作程序:

A.根据质量要求,按照评分标准,严格进行评分,同时填入表中。

B.对在检验过程中,发现的一些特殊和不清楚的疵点,可以当场询问工厂的质检人员,并取疵样。

C.在检验的过程中,一定要从严把握。

D.在进行随机抽查中,要做到认真细致,要按照逻辑办事,不要怕麻烦。

8.确定所有检验项目是否存在有漏验。

9.内在质量要求工厂进行测试,并提供报告,一些有疑问的疵点也要求工厂测试。

10.检验的过程中,如出现有质量问题,应及时向公司汇报,讨论具体处理的方案,同时也当场通知工厂的负责人,进行协调沟通,使问题能够及时准确地得到解决。

11.对包装的情况进行检查,根据公司具体包装要求,逐一进行核对。

12.向工厂索要船样,批样,厂检报告,如不能隔日回公司,应提前和船样寄回公司,分别将各天的检验报告传真回公司,如有疑问的痴样,也应寄回公司,以便及早确认。

13.每天汇报生产和检验的进度,征求公司的意见和次日工作的安排。

14.结束检验,离开工厂。

三.检验报告和总结的填写:

1.返回公司,填制检验报告,检验报告应包括总表(大致的评价),详细的布面检验情况表和重点项目评分表,所附的样品表,包装的情况表等,并要求相关的人员进行确认。

2.写检验总结,并E-MAIL发送给相关人员。

3.每个月5-10日填写前月检验情况表,并E-MAIL发送给相关人员。

四.检验的内容:

要根据不同的产品,不同的要求,严格检验,所检验的项目要全面,详细不能错过,没有或不能检验的项目要在检验报告上明确显示。

五.检验的依据:

对产品的检验我们都要一个明确的检验标准(如,国标出口一等品,10分

制,美国四点制,ITS,SGS等检验标准),每个检验的人员应熟悉并掌握不同的检测标准,以便能准确的进行检验。

六.检验报告的整理:

对于每次的检验报告,都应认真的整理,并保存好。

一般包括有总表,布面检验情况表,重点项目评分表,所附样品及内在质量测试报告和生产质量要求,将他们全部装订在一起。

七.检验总结:

在到达一个工厂后,由于在一个工厂停留的时间比较长,可以深入的了解一个工厂的具体情况,包括所去所经过的地方的风土人情,途径的路上是否有需要的信息

检验总结,可以有统一的格式,可以有自由发挥的地方。

但检验总结一定要对工厂的检验要逻辑,客观的评价

验货需要注重细节

一、经验(防惯例性出错)

一个公司的各个客户都有习惯性的要求,对产品对包装对装运对交期都有自己的特点。

一个好的验货员在进入一个新的公司或开展验货工厂之前应先对客户进行分类。

主要包括:

1、客人的产品分类。

2、客人的产品要求。

3、客人产品要求的认证。

4、客人对样品的要求。

5、客人对下单到交货的通常时长。

6、客人通常对产品配件和备件的要求。

7、各分类产品的质量要求。

8、客人的包装要求(外箱、内盒、标签、警语、安全性等等)

9、有时客人有惯用的色系、设计特色要掌握。

10、产品的功能性。

当看到订单有某些方面与此客人的习惯性性要求的不符要做到以下:

1、与业务确认资料正确(都是一个公司的,帮人发现了问题,人家会感谢你,同时你自己也上了一个层次)

2、如资料正确要用专门文件发到工厂,提醒工厂,并要求工厂确认签回。

二、勤奋(防小问题)

1、多上生产线。

你也学到了东西,同时在生产线上发现了问题,可以当场进行解决,不影响交期同时节省了工厂的成本。

比到出货前验货出问题要好。

2、多看配件、备件。

工厂订回了配件和配件,验货员能确认的当场确认正确,不确定的带回来给业务确认。

不会有问题。

3、印刷品。

每个单字都要对,版面设计布局、各个位置的印刷。

4、包装前最好要确认包装。

好多大货的问题不是出在产品上而是包装。

包装印错不仅是印错了几个字,鬼佬的管理与我们不同,错误的代号有可能让货物本来到南美却因为错误去了北美。

咱不说仓储的浪费和占用,就美国的运费都够你一年的工资了。

这只是打个比方。

所以包装很重要。

5、养成习惯带样品,生产样、出货样、包装样、配件样,多带只有好处。

三、厚脸皮(让自己放心)

厚脸皮是验货员必备的素质。

现实中太多的赖皮工厂,不自觉的工厂,没眼光的工厂,不重视你的工厂,公司内部也有好多不耐烦的业务。

厚脸皮是必要的。

1、现在年代不一样了,是贸易商求工厂做事,所以首先要放低资态。

2、结识工厂各部门的主管搞好关系,县管不如县管。

再说主管也没有高层那么高资态。

方便你做事,当然这并不说明可以帮你做好事。

还是需要你的监督。

3、不要因人情南昌觉得有些事难开口。

4、坚持原则,要骂随人,我们只要留住工厂,在公司内站住脚。

5、多说些话。

要人确认的东西,一定要得到签名的回复。